Was the Legend of Zelda Actually Named After Its Heroine?

Believe me, I totally get how the premise of this post sounds: “Everyone knows that the Legend of Zelda series was named after the game’s heroine, but what this post presupposes is… maybe it wasn’t.”

And while it seems like pseudointellectual wankery to ask a question like the one in the headline of this post, I swear there’s something here that’s not just worth interrogating but also that fits with what I’ve been doing with this blog as of late. Basically, I’ve been revisiting things that “everybody knows” in an effort to point out that the thing we all allegedly know might not be exactly accurate. It’s what I did with my piece on the origin of Dhalsim’s name — and to worthwhile effect, I should point out, as it resulted in the solution to that mystery! — but also in the one about why Donkey Kong throws barrels and the one about why Final Fantasy Tactics has two characters named after Beowulf. And silly though it might seem, this post might actually help solve a longstanding question I’ve had about why the Legend of Zelda series is called what it is.

The accepted origin for Princess Zelda’s name is that series creator Shigeru Miyamoto named her after Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, the artist wife of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s come up in multiple interviews, including this 2000 one promoting Majora’s Mask. And while I’m willing to agree that the Zelda Fitzgerald story is essentially true, there are some Miyamoto interviews where the chain of events that lead to the series name are stated slightly differently. For example, the January 1999 issue of the Japanese gaming mag 64 Dream (later Nintendo Dream) features interviews with the creators of Ocarina of Time, and as far as I know, it’s the first instance of Miyamoto explaining on the record how this series got its name.

From the get-go, we wanted the title to be The Legend of Something-Something, and consulted a songwriter. Then there’s this famous author named Fitzgerald who was married to a beautiful woman named Zelda. We thought it was a cool name and wanted to put it in place of the “something-something.” We asked if we could do so and got the okay. That’s how we ended up with The Legend of Zelda. There isn’t really any special meaning behind the name Zelda.

Translation for the caption under the image of Zelda: It seems the name “Zelda” came from the wife of the author of The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald. Her full name is Zelda Sayre, and she was known as an unparalleled beauty in Alabama and Georgia.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I am pretty sure that Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald was better known as a hard-partying flapper who suffered from various mental illnesses, but I guess don’t tell Shigeru Miyamoto that?

Notice how he doesn’t mention any princess at all, just the name of the series. He’d recall it slightly differently for 2011’s Hyrule Historia, the hardbound celebration of Legend of Zelda lore that Nintendo put out to promote Skyward Sword. The idea is coming from a PR person now, but it’s the same basic origin story, just with the suggestion being attached explicitly to both the series title and the princess.

Of course, the title of the game wasn’t decided right at the beginning. I knew I wanted it to be The Legend of Something, but I had a hard time figuring out what the “something” was going to be. That’s when the PR planner said, “Why don’t you make a storybook for this game?” He suggested an illustrated story where Link rescues a princess who is a timeless beauty with classic appeal, and mentioned “There’s a famous American author whose wife’s name is Zelda. How about giving that name to the eternal beauty?” I couldn’t really get behind the book idea, but I really liked the name Zelda. I asked him if I could use it, and he said that would be fine. And that’s where the title The Legend of Zelda was born.

The way Miyamoto recalls the process in both these accounts is that he needed a name for this fantasy-adventure series, he had a vague idea of what kind of name would fit, and when he heard Zelda Fitzgerald’s name, something clicked. This long-dead wife of a famous novelist had a name that approximated the grandeur and mystery that he wanted his forthcoming video game to have, and in the end it was given to the heroine of the story as well as the story itself.

What Miyamoto doesn’t say is that he always intended the game to be named for its damsel in distress. The fact that the series is named for a character who plays a fairly minor role in most of the early installments has always struck me as odd — and, notably, I’m not alone in this. Like, really: Why should Legend of Zelda be named for a character who generally only shows up at the end of the game? I’m thinking that this wasn’t the case, not technically. Princess Zelda is named after the series, and not the other way around. And that distinction might seem trivial, but I think it actually answers this lingering question as well as a few more.

For example, if Miyamoto was thinking that he’d name this game after the princess you rescue at the end, I wonder what the title would even mean. Like what, in the context of the first game, is the legend of Princess Zelda, exactly? Well, given the games that would seem to have inspired the first Legend of Zelda, which was released in 1986, I’d guess that Miyamoto’s desire to name the game The Legend of Something-Something probably stemmed from a desire to emulate the influential 1984 Namco game Tower of Druaga (ドルアーガの塔 or Doruāga no Tō), with the Japanese rendering of Zelda’s name (ゼルダ or Zeruda) sounding mystical and fantastical enough on its own, without any connection to a famous real-life woman. Once Miyamoto had the name that sounded good as a video game title — and once he connected it with feminine beauty — it also became the name of that game’s imperiled princess, even if she didn’t do enough in the game in question to merit being the title character.

To be clear, I’m just spitballing here, and I honestly hate the idea of taking anything away from female video game characters. Especially in the early 8-bit era, they got so little. But it’s because of them getting so little historically that I always wondered if some preliminary version of the first Legend of Zelda perhaps gave the princess more. Even if it was just a backstory that got scrapped from the final version of the game, that might have explained why Zelda was afforded this nicety that basically no other princess of her era got.

But yeah, if you end up here as a result of some online search to find out why the princess got her name in the title of the Legend of Zelda series, this is my best guess at an explanation.

Miscellaneous Notes

There’s no shortage of video games released around when Legend of Zelda debuted that match the pattern of “X of Y,” with Y being something that sounds mystical, foreign or feminine — and in some cases all three. Case in point: Wrath of Magra, Legacy of the Wizard, Magic of Scheherazade, Cleopatra no Mahō (literally “The Cursed Treasure of Cleopatra”), Golvellius: Valley of Doom, Return of Ishtar and even the sequel Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. Also it’s worth noting that at the time the first Legend of Zelda hit store shelves in Japan, but Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn had been hugely successful movies.

Alongside Tower of Druaga, another game that is thought to have influenced the first Legend of Zelda is Hydlide, which was first released in 1984. I was curious if that game title meant anything, and as near as I can tell it doesn’t as far as the game-playing public knows. The developers haven’t said. (For what it’s worth, the Japanese title, ハイドライド, is transliterated as Haidoraido, and I’m not sure if that means any more than the localized title does.) If it doesn’t mean anything in particular, then it might have that in common with the final word in Legend of Zelda’s title. Remember, after all that Miyamoto himself said that “There isn’t really any special meaning behind the name Zelda.” Tower of Druaga, meanwhile, is named for its villain. This makes sense; he owns the tower you’re ascending. The game is a melange of the mythologies of Mesopotamia, Sumeria and Babylon, and it’s speculated that Druaga could be a mangling of the name of a deity Drauga, but I don’t know enough about this game or these mythologies to weight in meaningfully

I want to return again to Miyamoto’s statement that Zelda’s name doesn’t mean anything special. If that’s true, then it’s a happy coincidence, given how the Triforce would become so central to the series mythology. The katakana for Zelda’s name, ゼルダ, is close that for delta, デルタ. As an English word, delta can mean a lot of things, but the primary visual association we have for this word is a triangle because that’s the shape of the Greek letter. This similarity may not have factored in during the production of the first game, but at the very least it may have been something someone at Nintendo realized by the time of The Wind Waker, as the alterego Zelda uses, Tetra, literally means “four,” so if you are supposing that Zelda = delta = triangle = three, then this alternate persona is kind of delta + one. It ends there, as far as I know. I’m okay with concluding this is a coincidence and nothing more, but I do think it’s an interesting one.

I’m not the only one to conclude this, but the backstory for Zelda II almost seems like an attempt to retroactively explain the series title that was established in the first game. In the instruction booklet (but not the game at all), you learn that the long-ago ancestor to the Princess Zelda from the first game had been put under a sleeping spell by her Little Lord Fauntleroy-looking princeling brother, who had fallen under an evil influence and who was trying to get his hands on the Triforce. Remorseful for putting this princess, also named Zelda, into a magic-induced vegetative state, the prince decreed that all princesses in the royal family should henceforth be named after his still-sleeping sister.

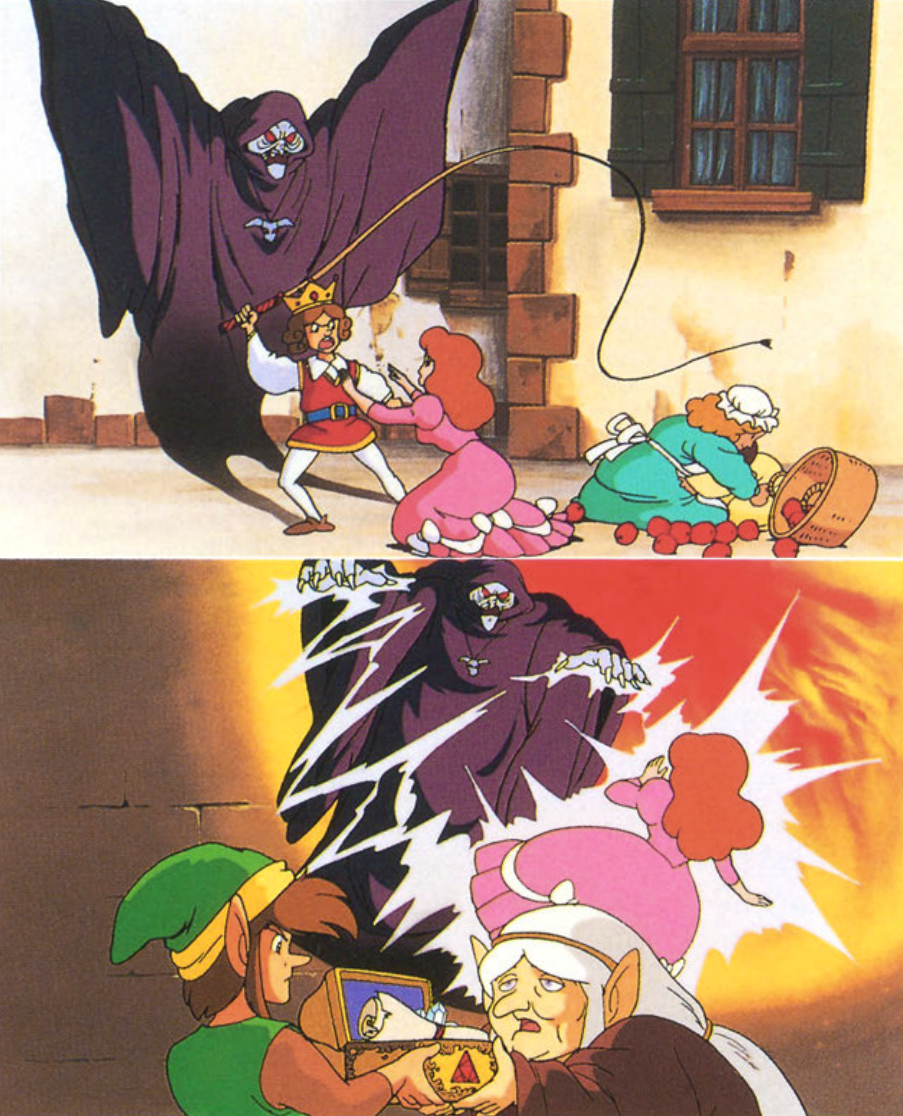

Top: I’m still mad this little prig wasn’t playable in a Hyrule Warriors game, whip and all. I can say it because I’m gay, but he looks really, really gay, and I dig a gay villain. Bottom: This, I think we can assume, is Impa literally explaining to Link the legend of Zelda — as in the one who was put under the sleeping spell and who cause the royal naming tradition.

This would seemingly be *a* legend of *a* Zelda, and I guess it’s enough to account for the series title, although it causes more plot problems that it solves. When Link awakens the sleeping Zelda at the end of this game, it would seemingly make for two Princesses Zelda existing at the same time. And this royal naming tradition never comes up again, although I suppose it would explain why so many different Zeldas exist in so many different games.

“You should name your fantasy game and also its princess after the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald” is such a weird suggestion for anyone to tell anyone, much less a PR guy to tell one of Nintendo’s game developers. I have to believe there’s something to this interaction that’s being left out, but I honestly can’t imagine a young Miyamoto saying that he hasn’t thought of a name for his forthcoming project yet and then some guy in the office just going to town on the virtues of Zelda Fitzgerald. Right? Yet somehow this pitch worked. So very strange.

In looking up the Miyamoto story in Hyrule Historia, I happened to notice a surprising factoid in the following paragraph: that Impa, at some point, was supposed to be one of the bearers of the Triforce rather than Ganon.

The old female storyteller who feeds information to Zelda is named Impa; her name comes from the word impart. Impa, Link and Zelda were guardians of the Triforce. Today, when you think of characters who are connected to the Triforce, you think of Link, Zelda and Ganon, but that started in Ocarina of Time. Originally, Ganon was only a villain in relentless pursuit of the Triforce.

This is such a strange thing to read, mostly because Impa was not a character who existed in the games until Ocarina of Time. Before that, she was a background character only who did not appear in the games but was only mentioned in the instruction manual as a sort of framing device. I actually did a whole post on how unusual it is that Impa transitioned from this to a central, active and sometimes even playable character in later sequels. Based on Miyamoto’s statement, I guess we can conclude that the idea for making Impa a more central character predates Ocarina of Time somewhat, but even then, I’m confused about the timeline. In the original Legend of Zelda, only two Triforces exist: the Triforce of Power, which has been stolen by Ganon, and the Triforce of Wisdom, which Princess Zelda has split into eight parts and scattered them in the various subterranean dungeons throughout Hyrule. It’s only in Zelda II when Impa reveals to Link that the Triforce of Courage also exists, and that obtaining it will break the other Princess Zelda’s sleeping curse. I guess it was kind of a given that something called the Triforce should exist in three parts rather than two, but the version of Impa that explains the third one — which, again, only happens in the instruction manual and not in the game at all — is quite elderly and feeble, so it seems surprising that she’d have been considered a Triforce guardian before she was given a stronger, more youthful look in Ocarina of Time.

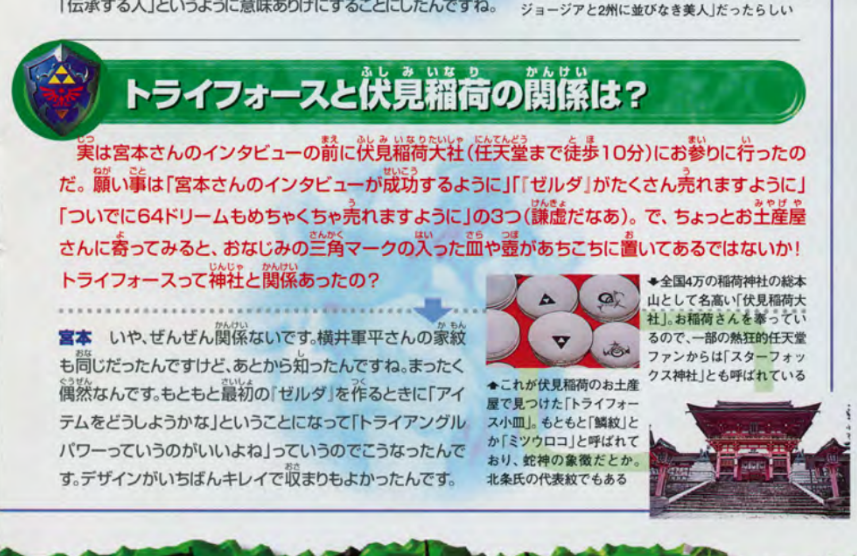

Speaking of the Triforce, the Nintendo Dream article that kicked this post off does have Miyamoto commenting on the similarity between the Zelda icon and an identical one seen around the Fushimi Inari Shrine, which is a short walk from Nintendo’s Kyoto offices. He says the Triforce was not inspired by this symbol. It is merely a coincidence.

Translation: Does the Triforce have any connection to Fushimi Inari? I actually went to Fushimi Inari Shrine (ten-minute walk from Nintendo) before this interview with you. I prayed for this interview to go well, for Zelda to sell a lot, and for 64 Dream to sell a whole lot — just a modest three wishes. When I stopped by a souvenir shop, I saw the familiar triangle symbol on plates and pots around the store! Does the Triforce have something to do with the shrine?

Miyamoto: No, not at all. It just so happens that the family crest of Yokoi Gunpei is the same symbol. We realized after the fact. It was seriously a coincidence. When we were first working on Zelda, we needed to figure out what to do for the items and thought, “Triangle power would be good.” The design was the nicest, and so we decided on that.

First caption: The small “Triforce plates” at the souvenir shop by Fushimi Inari. Originally called the uroko “scale” crest or mitsuuroko, it is said to represent the snake deity. It is also the crest that represents the Hojo clan.

Second caption: Fushimi Inari is the head shrine out of the 40,000 Inari shrines across the nation. Because these shrines are associated with foxes, some Nintendo mega fans refer to them as “Star Fox Shrines.”

That said, it was revealed in an Iwata Asks promoting Star Fox 64 3D that the Fushimi Inari Shrine did inspire elements of the original Star Fox game.