Is There a Sex Joke Hidden in Plain Sight in Zelda II?

I first played Zelda II: The Adventure of Link in June of 1989, which means I was seven years old and in the second grade. I was not a particularly worldly kid, I suppose, and a lot of innuendo went right over my head. But that said, my brother and I had a laugh at an element particular to this Zelda title. In each of the game’s villages, where Link can speak to various townspeople, there is a woman who invites Link into her house to restore his health.

The dialogue is the same for all the towns on the game’s first continent. You’ll see a woman in a red dress pacing outside a building with a locked door. If you talk to her, she’ll say, “Please let me help you. Come inside.” You have to be quick, because the door will only be open for a second or so after she heads in, but once Link is inside (and notably offscreen, along with the woman), you’ll see a second dialogue box that says, “I can restore your life.” And then, without specifically showing you how or why, your health meter will rise to full.

Here, watch the interactions as they play out in the game’s first two villages, Rauru and Ruto.

I am very certain that I didn’t know what sex was when I first saw this scene, but I had seen enough movies and TV to know that there was a certain thing that grown-ups did sometimes. I therefore clocked this interaction as… not racy, exactly, but the kind of thing that you were allowed to laugh about because it left the door open, to to speak, for the implication of raciness. As I got older, I remembered this part of the game and just defaulted to imagining that there was a more G-rated explanation for what Link and this woman in red were doing. This was a Nintendo game, after all, even if Zelda II famously does a lot of things differently than every other game in the series. But late last year, it was brought to my attention not only that might the innuendo been intentional but also that Link’s visits with the woman in red were actually part of a larger trend in the Zelda games.

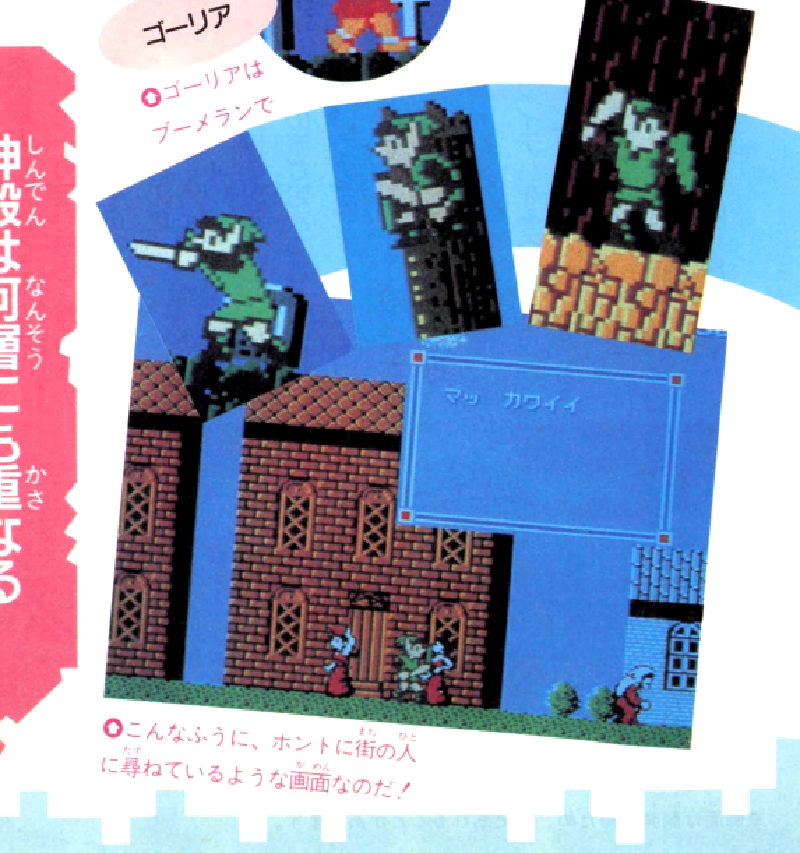

The Bluesky user MrTalida investigated by looking into a 1986 issue of Famitsu that featured a prototype version of Zelda II. Included in the screenshots is an early build of the town of Rauru that features the woman in the red dress in a different location than she appears in the finalized version of the game. What’s more, the dialogue box featured in the image would seem to show her saying “マッ カワイイ” (which he translates as “Super cute!”) rather than what she says in the original Japanese, which is “チョット ヨッテ イカナイ?” or something like “Why not stop by?” If his assumption was correct and Nintendo changed her dialogue from the former to the latter, it would seem to imply that the company wanted to remove or at least lessen the implication that the interaction was romantic or sexual.

In an effort to check whether this was actually the healer’s original dialogue and not something that was just spoken by another townsperson, MrTalida looked into the Japanese ROM and found that no, that Japanese phrase does not exist at all in the final product. He ultimately concluded that the prototype version of the woman in the red dress did seem to be commenting on Link’s appearance, which would seem to indicate that Nintendo originally wanted to suggest something but made the dialogue more neutral between the publication of the article and the release of Zelda II.

I think that MrTalida’s conclusion is correct, but this is where the baton is picked up by another video game historian, Melora Hart, whose Bluesky account History of Hyrule is a great follow because she shares rare retro materials related to the Legend of Zelda series. In the same Bluesky thread, she pointed out that the connection between healing and sexually charged interaction with female characters isn’t limited to Zelda II. For example, A Link to the Past features a character who functions like what later games would term a Great Fairy. She’s bigger than regular fairies, for one thing, and it’s implied she’s more powerful because while the others can restore Link’s health, she can help him in ways no other fairy can. Link’s interactions with her are fairly chaste, but the connotation of sex and romance is still there, in a way, because the game’s ending sequence reveals that she has a name: Venus.

And this name is not unique to the English localization, as the ending sequence vignettes in the Japanese version also use English text. In a way, it’s odd she has a name at all, seeing as how the end game text could have just referred to her as the Fairy Queen, but the fact that she’s named Venus is interesting because that gives her an association with the domain of Venus the Roman goddess, the counterpart to Aphrodite: love, beauty, sex, desire and fertility. And all of these would seem to be on the table as well during Link’s visits to the woman in red in Zelda II.

I can see why this association might exist. In fact, it might have evolved organically out of the first game. The original Legend of Zelda is notably lacking in any type of female presence. Aside from Zelda herself, who does not appear until the end of the game, Link only meets the old crones hiding in caves and then the fairies who restore his health. Some fairies appear when he defeats an enemy, but others wait for him at fairy ponds, Lady of the Lake-style. By some standards, the fairies make up the bulk of female representation in this game.

The squat dimensions of character sprites in this game make it hard to tell, but because they’re fairies, it’s implied that they’re smaller in stature than Link. It’s also clear that they’re meant to be humanoid, feminine and rather attractive, at least by the standards of ruined Hyrule. Now, Link’s health meter is measured in hearts, and that makes sense as a natural symbol for vitality, but the fact that the fairies restore his vitality with a flutter of heart magic also makes it possible to read the interaction as romantic, especially because it’s the male hero interacting with one of the only female presences in all of the original Legend of Zelda. Even the notion of restoring vitality is suspect, honestly. If you ever read old-timey literature promoting health tonics, phrases like “restores vitality” are often polite euphemisms for the promise of giving you the boners you can’t get on your own. Modern-day commercials for erectile dysfunction drugs even do a version of this today.

Vitality going up, up, up!

Later games would make the size disparity between Link and fairies a lot clearer, to the point that it’s more like how Peter Pan and Tinkerbell are usually depicted. This similarity is likely intentional, as Shigeru Miyamoto admitted in 2012 in an interview with French publication Gamekult that the Disney version of Peter Pan was an inspiration for Link’s look, but it’s also worth noting that in many adaptations of Peter Pan, Tinkerbell is in love with Peter and jealous of Wendy, despite the fact that their sizes would seem to make romance and sex difficult. (Though not impossible! Yes, I’ve been on Tumblr for a long time and have seen some shit.) Zelda II ditches the heart meter for a generic lifebar, but the woman in the red dress manages to preserve this connection to romance and sex — maybe even literalizing something that was an accidental byproduct of the visual language in the first game. So by the time Nintendo makes the third Zelda game, A Link to the Past, it doesn’t seem all that strange to give the name Venus to the most powerful symbol of this connection.

Hart pointed out one more connection that I was chagrined for never realizing myself. When we get the introduction of proper Great Fairies in Ocarina of Time, it’s about a year and a half after the release of Batman & Robin, the fourth and final installment of the original Batman movie series, and Uma Thurman’s Poison Ivy would seem to be a visual inspiration for the Great Fairies. Their make-up, hair and costumes greatly resemble the different looks Ivy sports in that movie.

I totally see it now, and I don’t know how this never occurred to me before. Poison Ivy is my favorite comic book character, and while the Batman & Robin version of her isn’t my favorite, it is one that introduced a lot of people to this character. And it’s pretty iconic in the way it departs from the softer greens with which she’s usually depicted in the comics; thanks to the vivid palette that Joel Schumacher brought to his Batman movies, this version of Ivy is the personification of the “look but don’t touch” warning that some plants give with neon colors. Combined with Thurman’s performance, the movie gives the character more of a campy, draggy vibe than she’s ever had before or after. But it’s worth pointing out that the Great Fairies in Ocarina of Time are also fairly campy and draggy, so it’s maybe even possible that this exists in the game because it exists in the movie.

I mean how else should we read this grand entrance? That laugh?

And it’s not limited to Ocarina of Time, either. Hart also notes that Ivy’s labial throne in Batman & Robin would seem to be reflected in the Great Fairy housings in Breath of the Wild.

Again, I totally see it, but at this point it’s also possible that the Zelda fairies have become so tied to this melange of the floral and the sensual that the artist responsible could have just taken the association to the most logical conclusion by having them pop out of vagina flowers in Breath of the Wild. Georgia O’Keefe would be proud.

So while we can’t say with certainty that the Zelda II assignations were meant to seem sexual, it wouldn’t be the only instance in the series to imply sexual healing. And the fact that this connection has been present in so many other Zelda games, sometimes subtly and sometimes not, make me think that it doesn’t seem like too much of a stretch to conclude that yes, this is exactly what it looks like.

That’s enough of an ending for this post, but I also wanted to point out that this analysis exists thanks to a group effort on the part of MrTalida, Melora Hart and now me, and I’m stoked to see if anyone else can take it even further. My favorite version of the internet is when a bunch of nerds can “yes and” each other and end up drawing meaning out of pop culture that no one else bothered to consider in any depth. This is definitely that, and I’m bat more ideas like these around to see where we end up.

Miscellaneous Notes

Hart includes some analysis of how the woman in red is depicted in various manga adaptations of Zelda II. Yes, they also pick up on the innuendo. The one appearing below comes from one by Yuu Minazuki in 1987, but you can see more here, here and here.

Each town in Zelda II features a wise man who will teach Link a magic spell. This is explained explicitly by one of the townspeople in the first town you encounter, just so you know to look for them in every new town. What’s interesting about this is that every town also includes a healer woman, but it’s not something the game ever tells the player outright, unless I’m mistaken. If I’m right, it’s kind of weirdly true-to-life for a video game from this generation, in that there are some things people in small towns want to talk about and other things people will take pains not to mention. If you know, you know.

While fairies in Zelda II will still heal Link the way they do in the first game, there is one way they figure into the game that is so far unique to this title. One of the spells Link learns turns him into a fairy that can flit over dangerous situations and even pass through locked doors if Link has failed to find a key. It’s very handy, but what’s odd about it is that in fairy form, Link does not look like a smaller version of himself with wings. He’s given the sprite of the regular fairies, which look distinctly feminine. If that weren’t enough, the instruction manual illustration is very… sugar plum fairy? She’s got a saucy bob, a pink dress and a magic wand.

This is notable for a few reasons. Even if this is a game that has Link bouncing from town to town to meet the local talent, it also has him turning into a pretty pink pixie. This might be the first of many moments in a Zelda game that make Link seem a little feminine — or at least a little less masc than we’d usually expect from the main character in a video game. But it also makes me think of a little factoid bouncing around in my head about Nintendo considering multiple playable characters in Zelda II. As I remember it, there was a notion early on that the player could control characters in addition to Link, each with their own special power. I’d been thinking for a while that Link’s fairy form is the one vestige of this idea that made it into the final version of the game, but for the life of me, I’ve not been able to find this information anywhere online. Am I misremembering? Please let me know if you have any idea what I’m talking about.

It’s mentioned in the original Bluesky thread that in the English version of Zelda II, the healer women have different dialogue in the towns on the game’s eastern continent. Arguably it’s even more suggestive: “Stop by for a while,” followed by just “Revived!” once Link is inside. There’s no mention of healing. I’m not sure how this compares to the Japanese version, however, as no one in the thread said how the women say it in Japanese in this region of the game. Anyone?

The official title for the fairy fountain theme in A Link to the Past is “The Goddess Appears,” and that might seem surprising since this game is the one that introduces goddesses to the series canon, but these are actually different characters that the fairy queen — it’s technically Din, Farore and Nayru, although they’re not given those names until Ocarina of Time. So is the music track titled what it is because the fairy queen character is named Venus, which is a goddess’s name? I’m not sure. For what it’s worth, it seems like the Japanese version is the same way, as the corresponding track name is 女神が現れる (Megami Ga Arawarer or “A Goddess Appears”).

Things more or less sexual, previously: