Hylian 101: The Secrets Hiding in the Language of Zelda

Ocarina of Time introduced many elements that would become mainstays in the Legend of Zelda series. Among them is the concept of other humanoid species living alongside Link and Zelda’s people: the Zora, the Goron, the Kokiri and the Gerudo.

The Zora technically have been part of the series since the first game, but as a recurring enemy. Although they revealed that they could talk in A Link to the Past, it’s Ocarina that redefines them as friendly, civilized merfolk. The mountain-dwelling Goron are original to Ocarina of Time, with only their tendency to roll like a boulder to link them to anything that showed up in a previous title. The Kokiri — the “children of the forest” — look and dress like Link, and their introduction seems like an attempt to provide an in-universe reason for Link’s “uniform.” And finally there’s the Gerudo, the desert tribe that is basically all-female except for a single male member born every hundred years. Ganondorf, who will become the pig-faced big bad Ganon by the end of Ocarina of Time, happens to be the latest male Gerudo, so this group is immediately put in the center of Ocarina of Time’s story, but there’s not much in the series lore to hint at the existence of the Gerudo beforehand. You can, however, find whispers in previous games of something that’s not exactly humanoid but nonetheless alive and connected to the desert. It’s almost as if there’s this spirit in the sand that wants to exist, taking different forms before coalescing into the amazon tribe we know today.

For example, in A Link to the Past, there’s a sort of sand golem monster that lurks in the dunes surrounding the Desert Palace. In the English localization, it’s named Geldman, which doesn’t sound like anything in particular, but the original Japanese is ゲルドマン or Gerudoman, suggesting that someone working on these games had the idea to attach the name to the desert before Ocarina of Time.

Link vs. Geldman, from A Link to the Past.

It goes back even further than this. The desert areas of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link feature these generic enemies that look more or less like centipedes but which raise up vertically, blocking Link’s progress until he kills them. In English, they’re the Geldarm, but in the original Japanese you see that same root again: ゲルドアーム, which could be transliterated as Gerudo Āmu. You might even guess that the second part of the name might be arm, because the English word is rendered in katakana as アーム (āmu) and the bug sticks up somewhat like an arm, but put a pin in that, because there’s a more Zelda-specific theory for what that could mean.

As an English-speaker, I’d guess maybe there’s something in Japanese that connects this root to the desert. There’s not, as far as I or anyone else looking into the origins of Hylian linguistics can tell. What’s more, there doesn’t seem to be anything in anyone else’s language that sounds enough like gerudo and refers to something desert-related.

No, instead it would seem that this desert name would fall into a category of Legend of Zelda names for persons, places and things that don’t come from any real-world culture. Many names in the series derive from Japanese roots. Others come from English, and some even come from a fusion of Japanese and English. But then you have ones that, like gerudo and its predecessors, don’t seem to descend from any language in particular but nonetheless recur though the series in a way that shows that somebody somewhere gave them a specific value. The technical term is morpheme: the smallest bit of language that can still convey meaning. For example, the English word break is a morpheme, but so are the prefix un- and the suffix -able. Assemble these three morphemes together and you have a new word: unbreakable. Someone who did not know this word but did understand the meaning of the three morphemes comprising it would be able to guess what it means. Based on the three examples I provided, there is something about the morpheme that we’d represent in Japanese as ゲルド and in English as something like gerudo or gerud or I guess even geld that, in the world of Zelga games, should tell you that you’re dealing with something related to the desert.

It is not the only example in these games hinting at some kind of linguistic throughline.

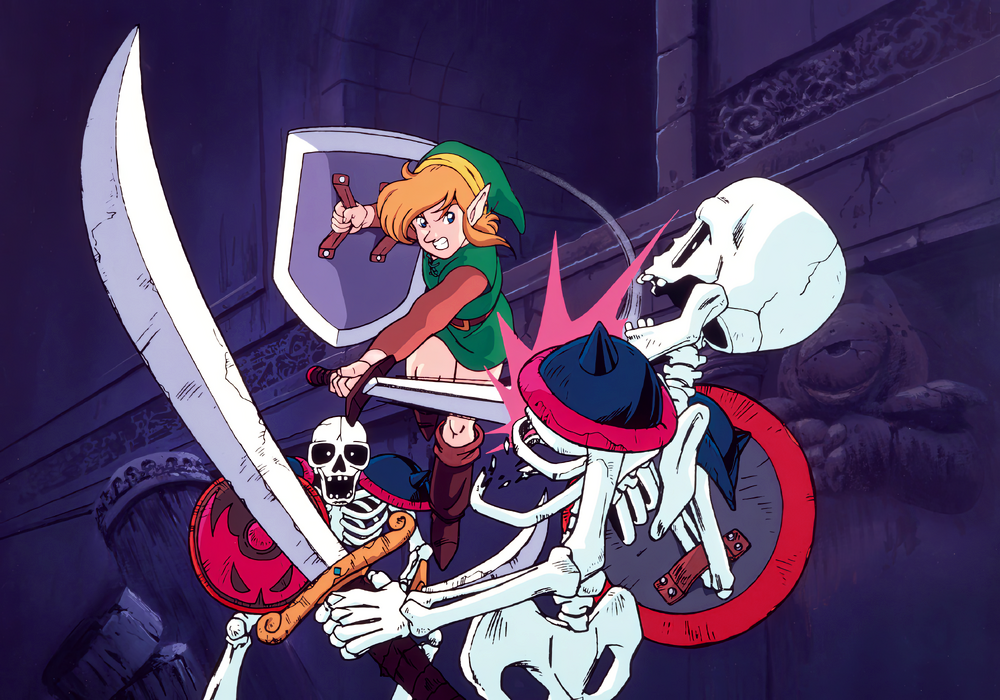

Link vs. Stalfos, from A Link to the Past.

For example, there is a suffix -fos dating back to the original Legend of Zelda that would seem to refer to some type of weapon-wielding enemy creature that approaches humanity without quite clearing that bar. Stalfos are the skeleton warriors Link fights in dungeons. It’s the only example in that game. Goriya are the boomerang-tossing beastman that walk on two legs, but they don’t use the suffix, and neither does the upright mummy monster Gibdo. Adventure of Link introduces a bipedal reptile warrior, Geru, as well as a bipedal canine warrior, Wosu, that both seem like they should use that suffix but don’t. It actually takes until Ocarina of Time to get two more that do: Lizalfos and Wolfos, and I’d bet that someone who has never played a Zelda game would be able to guess that they are a lizard warrior and wolf warrior, respectively. It evolved from there. Twilight Princess, for example, introduces an all-ice version of this enemy, Chillfos, and its name also makes sense, I suppose, even if it always sounds to me like some kind of cool ranch-flavored snack product.

The other word part in Stalfos’ name has meaning as well, though you’d have to play a few Zelda games to realize that the series uses that word part stal- to mean “skull” or “skeleton.” The Stalchild is a skele-grunt that attacks when you stray from the path in Ocarina of Time, for example. The Japanese name of the Skulltula, the collectable skull-looking spiders, is スタルチュラ or Sutaruchura — essentially Staltula. Twilight Princess has the Stalhounds. Even the Skull Kid, the antagonist of Majora’s Mask, is known in Japan as スタルキッド or Sutarukiddo — Stalkid. And skeletal Captain Keeta’s Japanese name is スタル・キータ or Sutaru Kīta — Stall Keeta.

The first Legend of Zelda game also introduces the recurring enemy Armos, essentially a suit of armor that comes to life when Link gets too close. You might think this was missing from the -fos group. It might be, but it might also be an example of a different Zelda morpheme, either -mos or -os, referring to… robots? Or at least mechanical security systems? How else to explain why the laser beam-shooting eyeball monsters that debut in Link to the Past are called Beamos? Weirdly, A Link to the Past also features a bovine variation on the -fos enemy that inexplicably uses the -os suffix: Taros, which seems like it should have been called Tarfos if they’d realized the pattern by then.

Moblins (and one Goriya) vs. townspeople, from Adventure of Link.

I suppose the -blin suffix also technically falls into this category, even if we know where it came from. Since the first game, Link has encountered Moblins, which are forest-dwelling, ogre-like baddies that either look like bulldogs or pigs, depending on where in the series you’re looking. The Japanese version of their name is モリブリン or Moriburin, and it’s apparently a combination of 森 or mori, meaning “forest,” and the English word goblin. What’s interesting about the -blin suffix’s evolution over the course of the series is that starting with Wind Waker, Moblins have shown up less frequently than the smaller variants, Bokoblins. Weirdly, their names mean about the same thing, because starting with Wind Waker, boko is used to mean “forest” as well, just using a Hylian root rather than a Japanese one. The Boko Baba, for example, is a carnivorous plant monster that shows up in forest areas in Wind Waker.

And that’s not even the only Zelda root referring to the forest. Before boko came into vogue in Wind Waker, the term used in Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask was deku, as in Deku Nuts, Deku Baba, and Deku Scrubs. It could be that all uses of deku in these games are in reference to the Great Deku Tree, which also debuted in Ocarina of Time, but without any insight as to precisely what the term means or where it comes from, we don’t have an explanation for why the series switched from one to the other. (I suppose it’s worth pointing out that in Japanese 木偶, deku, means “puppet” or “wooden doll.”) For what it’s worth, the Great Deku Tree as a specific entity appears in Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom, using the old name despite the overall switch to boko; it does not become the Great Boko Tree.

But to go back to the Boko Baba and Deku Baba for a second, some people point to baba as being a Hylian root referring to carnivorous plants in general. I see the logic here, though it seems to me like it might just be a generic species name, especially because it so far stands on its own instead of being used as a suffix or prefix. The Baba Serpent in Twilight Princess, for example, is a snake-like variant of the typical man-eating plant, in the way that the ground squirrel and the tree squirrel are two different varieties of the same family of animals. I suppose it could go either way, especially because we don’t have any official indication of what baba could mean.

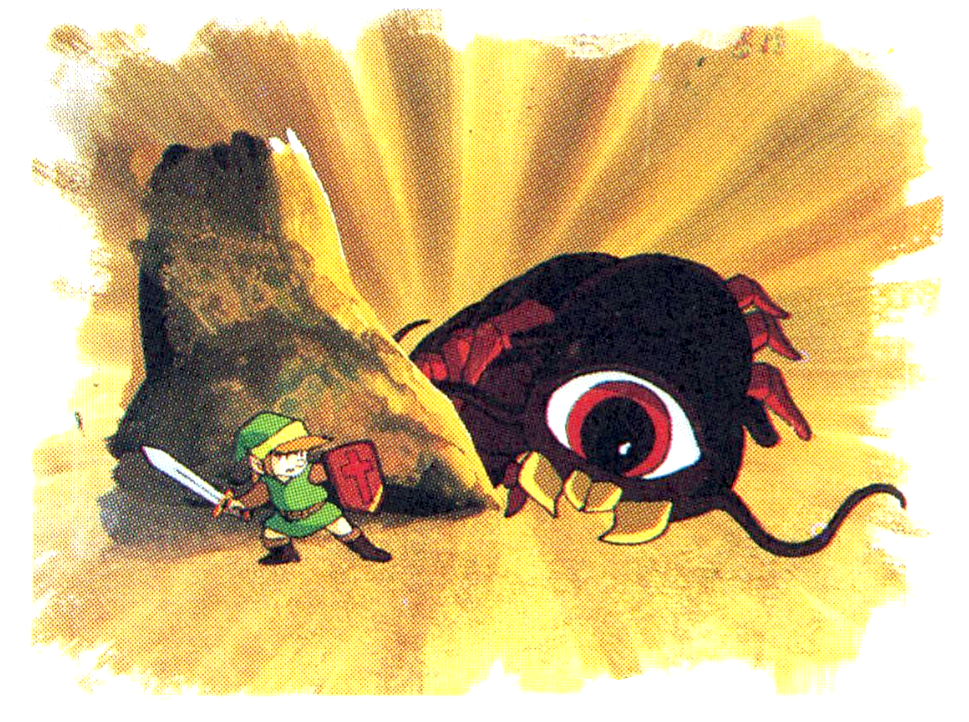

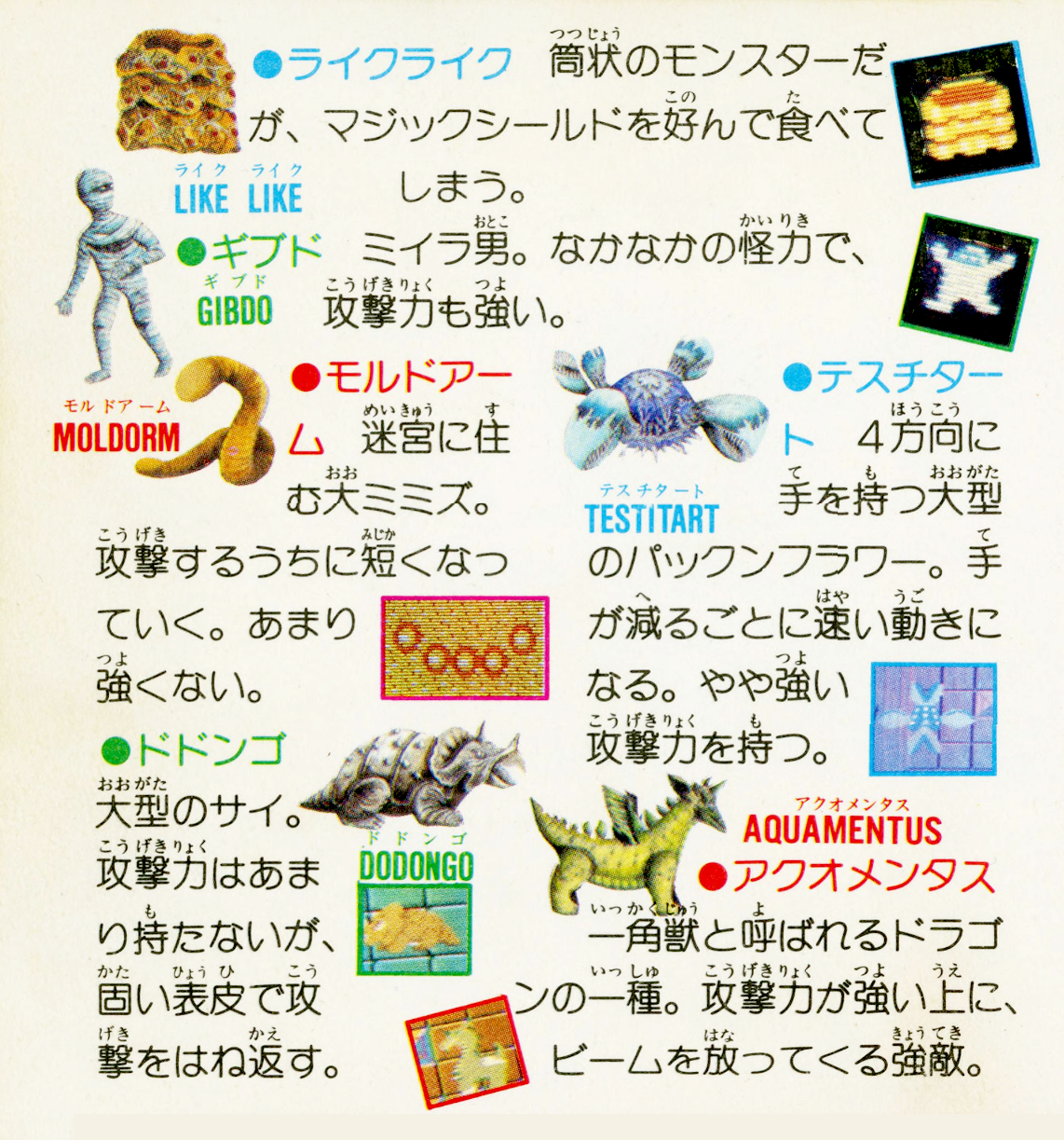

Then there’s an especially complicated one that early on seemed to refer to… crawly, wormy things, I guess, before evolving in later games to refer more generally to creatures that burrow. It’s particularly odd because it can function as a prefix (mol-) or a suffix (-mol). You can see both usages in the original game, in fact. The Moldrom is a multi-segmented, worm-like monster appearing in dungeons, while the Lanmola is a more specifically centipede-like monster that only appears in the game’s final dungeon. In Japanese, the names are rendered slightly differently, with Moldrom being モルドアーム or Morudoāmu and with the Lanmola being ラネモーラ or Ranemōra, so it’s possible that they weren’t originally intended to be part of a set, so to speak.

Link vs. a Lanmola, via Legend of Zelda.

A Link to the Past corrects this to a degree, but of course, it’s not clear or straightforward at all. In that game, the enemy that’s referred to in English as a Moldorm is known in Japanese as テール or Tēru — literally “tail,” but there’s also a swamp-dwelling relative that in English is called the Swamola but in Japanese is モルドアーム or Morudoāmu — Moldrom. It’s a weird do-si-do of names, but I think it’s notable that this early on, the English name Swamola — presumably a combination of swamp and Lanmola, was already starting to play on the enemy name’s morpheme qualities and presuming that players would grasp the connection to the Lanmola just by name alone.

The Zelda Wiki attempts to connect the -mol- affix to the English word mole, the connection being that more recent examples burrow through the ground, but I’m not sure that necessarily makes sense because the examples seem more specifically connected to the desert. In Wind Waker, the Molgera is a sand-dwelling boss. In Skyward Sword, the Moldarach is a large scorpion-like monster in the desert. And in Breath of the Wild, the Molduga are fish-like monsters that move through sand. Perhaps supporting the mole theory is the fact that each of their names use the katakana rendering of the English word mole: In order, モルド・ゲイラ or Morudo Geira, モルドガット or Morudogatto, and モルドラジーク or Morudorajīku. Incidentally, it’s worth pointing out that the Moldrom’s Japanese name ends in アーム (āmu), which is the same morpheme that appears in the Japanese name of the Geldarm (ゲルドアーム) from Adventure of Link. Does this mean that the Zelda series uses アーム (āmu) to refer to long, skinny creatures? Maybe!

That’s more or less it, at least as far as the collective studies of the Zelda fan community. I should point out that of what I’ve written so far, I only did the detective work on the gerudo thing — and even then, that was something that the other people exploring this had realized already. I can’t remember where I first encountered the idea that there’s a sort of linguistic structure undergirding the names in the Zelda games, but I’m sure it was some message board somewhere, maybe going back to the early 2000s, maybe as part of the infamous NeoGAF “cloudbush” thread. All these years later, however, the research so far has been collected in various places, including on the community glossary page of the Zelda Wiki. I’ve got some more, however, and while I’m sure Zelda aficionados here and there have thought of these as well, they’re not yet realized in most summaries of this specific field of study.

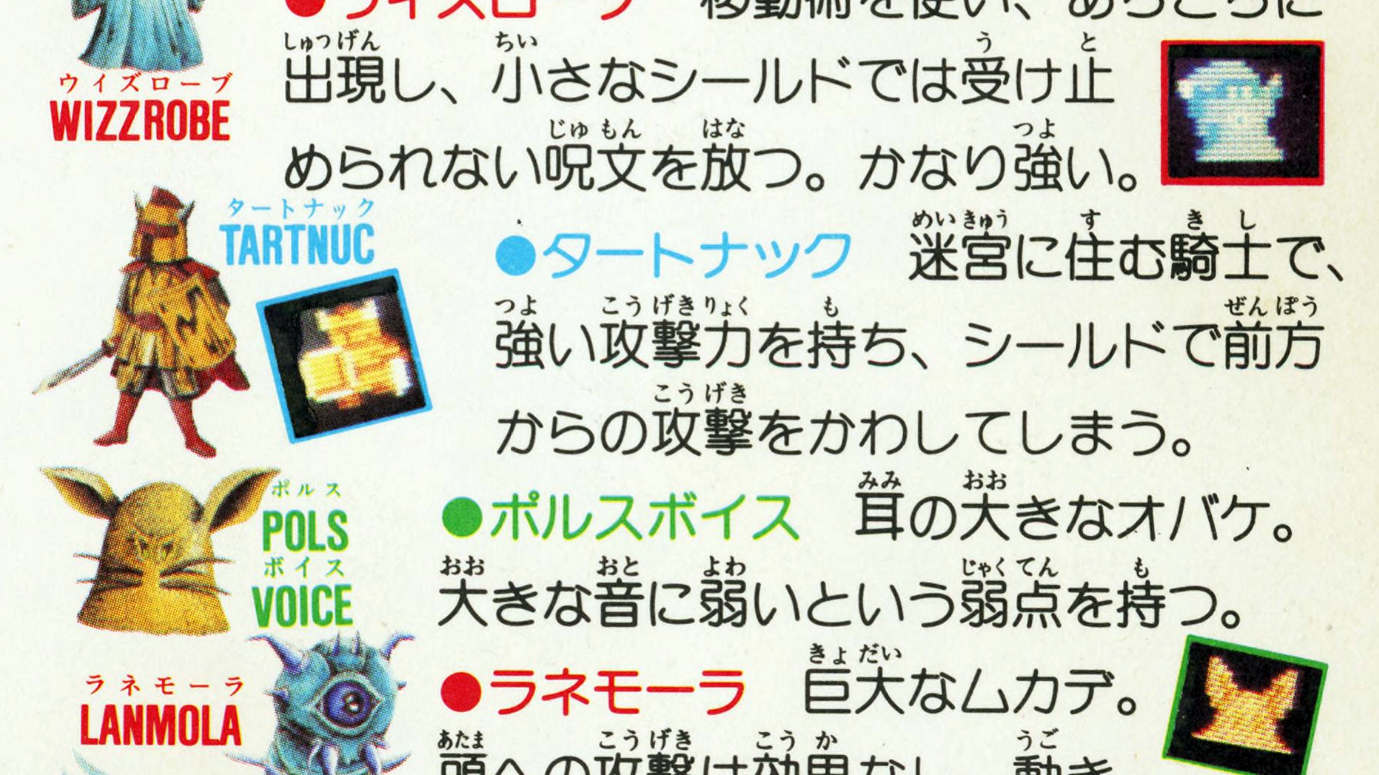

For example, there’s an enticing connection involving the Darknut and the Iron Knuckle, which are two armor-clad enemies appearing in the Zelda series, although notably never in the same game. The Darknut, whose name is actually very weird when you think about it, debuts in the original Legend of Zelda, and the Japanese version of its name, タートナック or Tātonakku, can be rendered in English as Tartnuck or Tartnuc. That’s how it’s featured in the original Japanese version of the instruction manual, at least, in reckless disregard for any type of western naming practices.

The Tartnuc in all his tarty glory, via the Japanese version of the Legend of Zelda instruction manual. (And yes, I will be devoting a whole post to the Pols Voice and its mysterious etymology. And no, I will not be doing the same to the Wizzrobe because come on.) Via archive.org.

Because the English word tart can mean a few different things, none of which are particularly appropriate for an evil knight-type character, subbing in dark for the first syllable makes sense, but I don’t have an explanation for how or why that last syllable became nut. Zelda II: The Adventure of Link introduced a new enemy that looked and acted like the Darknut but which was apparently unrelated based on its English name, Iron Knuckle. Its Japanese name, however, is アイアンナック or Aiannakku, presumably a katakana rendering of the English word iron, アイアン, and the last three characters from Darknut’s Japanese name, ナック or nakku. Whoever was localizing the game for English-speaking territories either didn’t notice the Darknut connection or thought they could improve upon it, and the Japanese name was rendered in English as Iron Knuckle, which sounds cool but doesn’t necessarily make sense, because these enemies fight with a sword and a shield and not with their knuckles. In Adventure of Link, the third palace boss is a horse-riding Iron Knuckle, Rebonack, whose English name features yet another interpretation of those final three katakana, as his Japanese name, レボナック or Rebonakku, makes it clear that he’s part of the same “family” of enemies. Whatever the case, Darknuts and Iron Knuckles have been mutually exclusive ever since, with the former appearing in Wind Waker, Minish Cap, Twilight Princess and Echoes of Wisdom, and the latter appearing in Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask and Cadence of Hyrule. So far, they’ve never overlapped, which to me would indicate that they’re one and the same, just named differently.

All of this is complicated by a total outlier that nonetheless shares a morphemic connection: Manhandla, the third dungeon boss in the original Legend of Zelda and the subject of one of my first posts on this site. This monster has a radically different name in the original Japanese version of the game: テスチタート or Tesuchitāto, which is officially rendered in romaji as Testitart, with the connection of tāto = tart connecting it to Darknut’s Japanese name despite the fact that it doesn’t look or act like any of these armor-clad monsters and also despite the fact that per the Japanese instruction manual for the game, this dungeon boss is actually an overgrown Piranha Plant from Super Mario Bros. I surrender to your best guesses for how to make sense of this, because I literally can’t make heads or tails of it.

From the Japanese Legend of Zelda manual, the description for the Testitart reads as follows: “A large Pakkun Flower with limbs in all four directions. It moves faster as the number of limbs decreases. Has a somewhat strong attack power.” And yes, BTW, I will also be doing a post on the Like Like’s baffling name. (Via archive.org.)

We also have some evidence for the root -doga meaning *something* in the universe of Legend of Zelda, but I’m not sure what. It first shows up in the name of a different boss from the original Legend of Zelda: Digdogger, whose Japanese name is デグドガ or Degudoga. There is literally nothing about this monstrous eyeball creature that lends itself to digging or dogs, and in fact it’s another crossover reference to a different Nintendo series: Clu Clu Land, where the main enemies are sea urchin monsters called Unira. None of that seems to be referenced in the name, however, but oddly enough the latter two syllables do show up in a boss from Link to the Past: Vitreous, whose Japanese name is ゲルドーガ or Gerudōga. Both Digdogger and Vitreous are eyeball-centric bosses, so I suppose it’s possible that there’s something about that root doga that refers to eyes. But these are the only two examples of this trend in the series, as far as I have found. I would imagine that there are more, as well as whole separate linguistic trends that just haven’t been spotted yet.

What can we make of any of this?

Some fans point to these connections and claim that Hylian has over time developed some of the qualities you see in fictional languages in other continuities, like Elvish in Lord of the Rings, Klingon in Star Trek or Dothraki in Game of Thrones. This is technically true, I guess, in that we can isolate morphemes and say that the games provide us some evidence for what some of them are supposed to mean, but I think it would be a mistake to imagine that someone at Nintendo actually figured out an internal structure for the language of Legend of Zelda of which the games are only showing us glimpses. Elvish, Klingon and Dothraki are all constructed languages — or conlang, to use the lingo of people who traffic in fictional lingo — that were meticulously formulated in a deliberate effort to deepen the worlds of their respective franchises. I feel like if such a thing existed for the Zelda games, Nintendo would just show us — perhaps even selling it in a hardbound book, not unlike how the Hyrule Historia forced upon us the idea of the various games fitting into an interconnected timeline. I mean, I know I’d buy it if it existed. Nintendo probably knows that too.

Rather, I think the scant evidence we have for any sort of linguistic continuity is more likely proof that the people who work on these games share our love for them — and understand what it means to be fluent in the worlds that these games inhabit. Sure, some additions to the series come from out of nowhere, but a lot of them call back to the games that came before, sometimes in subtle ways, and that attention to detail lets superfans know that the creatives tasked with making new Zelda games have done their homework.

I think about this in context to how the series figured out what it was, so to speak. The first Legend of Zelda introduced a host of new names, and as I said earlier, some of those names come from Japanese, some from English and some neither and possibly no real-life language at all. Next came Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, which sought to differentiate itself from the predecessor in scope, gameplay style and also in its bestiary, which is why a lot of monsters from the first game don’t appear. In their place are new ones who largely don’t appear again. I’d guess this results from the fact that while considered a success in its day, Zelda II never enjoyed the prestige the original did and still does, and that’s why the next three mainline Zelda games — A Link to the Past, Ocarina of Time and Wind Waker — each hew more closely to that first game. As a result, what might seem like a new thing in one of these games often turns out to be rooted in something from the original, with a linguistic callback helping to make the connection clearer. Hence the Lizalfos and the Wolfos becoming mainstays of the series when very similar monsters introduced in Zelda II — Geru and Wosu, in that order — have yet to appear again.

This theory makes the most sense of the weird pre-history of the Gerudo, who are every bit as new to the Zelda series as the Gorons and the Kokiri are when introduced in Ocarina of Time. I know I said the Zora date back to the original game, and they technically do, but if you compare how they look and function in Ocarina of Time versus the previous games, they’re drastically different. You could say that the friendly, civilized versions are Zora in name only — essentially a new invention given a literally nominal tie to something that came before, to reinforce the idea that these games share a continuity.

Left: The Zora as it appears in Adventure of Link, all toothy and monstrous: Right: The most famous Zora in Ocarina of Time, Princess Ruto who is much more humanoid, essentially nude the entire time and also sexy (???). Also why does a merperson have breasts?

This is basically the case with Gerudo too. It’s not that the Hylian language was hinting at their existence in Adventure of Link and A Link to the Past, with the actual Gerudo tribeswomen existing just beyond the confines of those games. It’s that they were invented wholesale for Ocarina of Time, and I’d guess that when picking their name, someone on the development team looked back at the previous games and saw a little chunk of syntax that had previously been used in connection to desert-dwelling things and decided to repurpose it and expand it beyond what it was ever intended to mean. As a result, the Gerudo become a major recurring part of the series lore, and they just make sense, as if they’d always been part of the game, even if they were technically a late addition.

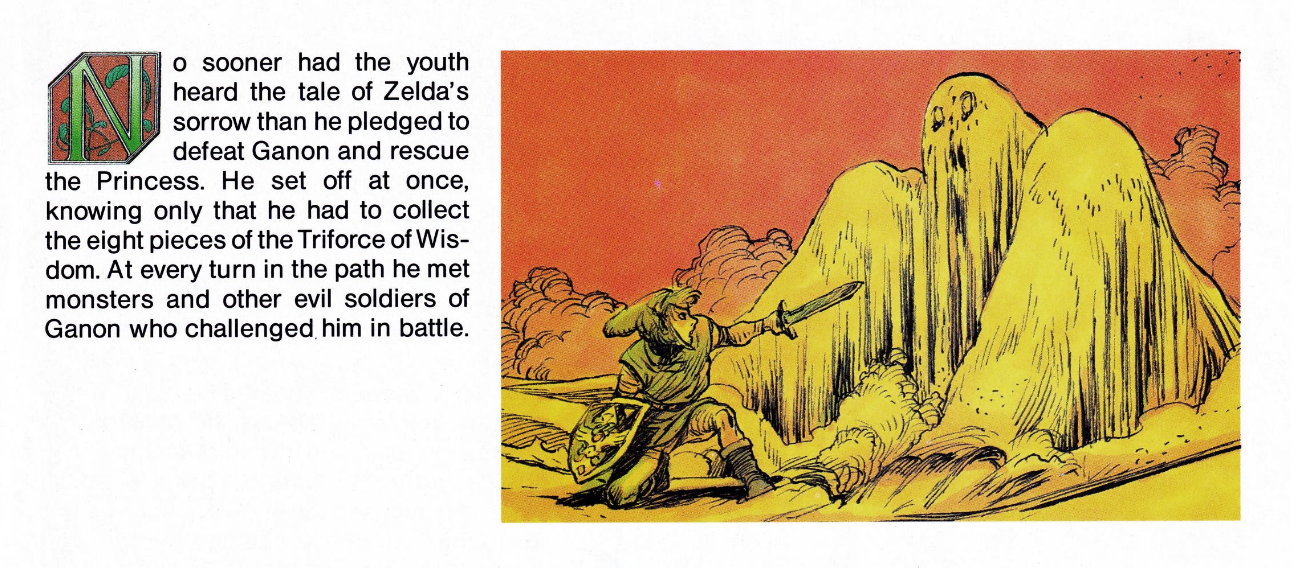

It’s probably just a mistake, but there’s actually one more way that Nintendo attempted to fudge the timeline, so to speak, and make it seem like this desert presence truly had existed in the series going back to the first game. The official Nintendo Power Player’s Guide for A Link to the Past devotes a few pages to telling the story of the first two games, complete with original illustrations. In depicting the original Legend of Zelda, the guide shows Link battling what looks like a Geldman and certainly doesn’t look like anything that actually appears in that game.

Obviously, the simplest explanation is editorial oversight. But even if that’s the case, this does reinforce the idea that no, these elements were always part of the series, even from the beginning, even if you don’t remember them, even if you could swear that no desert sand monsters appeared in the original game. Based on the way the lore of the series has evolved, the Gerudo probably should have been there from the beginning. And if you squint just right, I guess they kind of were?

Miscellaneous Notes

Initially, I was going to discuss the usages difference between Hyrule and Hylia — and by extension Hyrulean and Hylian — but the more I looked into it, the more I realized this deserved to be its own post, so for the moment I say look forward to that in the future. If you have any usage notes on how these terms differ or what their etymology might be, hit me up.

If we’re talking about Hylian in terms of being a conlang, I should probably point out that there are a few people who have attempted to create a working version of the Legend of Zelda’s language. There’s one at Kasuto.net, for example, and I’m sure there are others. I think it’s cool that they exist, but until Nintendo puts out something more official, they’re not something I’m going to look at too closely.

Some discussions of Hylian roots will also point out that -tula gets used in the names of various spider-like creatures, most notably the Skulltula. And this is true, but that suffix is so obviously just borrowed from the English word tarantula that it just didn’t seem interesting to me. Unless it’s used more subtly in other forms, I didn’t think there was much to say. Is there? Ditto uses of -roc in names associated with birds, mostly because there is the mythological Roc that I feel like they’re all named for?

There’s an interesting sense of linguistic drift that starts to appear in the more recent entries in the Legend of the Zelda series, in which you can see names reflecting those that appear in previous games but they’ve evolved to the point that the reference isn’t always immediately clear, much in the way that language evolves in real life. For example, it’s in Ocarina of Time that we first get the names of the three Hylian goddesses, Din, Farore and Nayru, who each represent one of the three Triforces. Twilight Princess features locations whose names seem to reference these deities: Eldin Province, Faron Province and Lanaryu Province, each changed just enough that their namesakes aren’t obvious. Nintendo really doubled down on this in Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom, in which a lot of less major Zelda characters are seemingly referenced in location names. Aquame Bridge and Aquame Lake, for example, seem like they’re named for Aquementus, the first dungeon boss from the original Legend of Zelda. Similarly, Rebonae Bridge sounds like a nod in the aforementioned Rebonack from Zelda II. Malin Bay is probably named for Marin from Link’s Awakening. Aldor Foothills are probably named for Aldo, a Korok from Wind Waker. Lake Kolomo might be named for the Lokomo from Spirit Tracks. And Brynna Plain is probably a reference to Labrynna, the setting of Oracle of Ages. Like I said, the people creating these games want to make it seem like they did their homework, and as far as I’m concerned, the harder to spot the reference the better. I’m sure there are more subtle ones I’ve missed.

Maybe one of the more famous incidents of a Zelda game re-using names to enforce a connection to a previous entry would come from Ocarina of Time’s sages. Nearly all of them share their names with towns from Zelda II, in a way that suggests later generations of Hylians named these places in honor of them. What’s interesting is that the associations don’t always line up. Saria, for example, is the forest sage, but the Zelda II location is specifically called Water Town of Saria due to its location on a river. Meanwhile, Ruto is the water sage, but Ruto Town has no water affiliation. Nabooru, the spirit sage, is the leader of the Gerudo, but Nabooru Town is not one of Zelda II’s desert towns. Only Darunia, fire sage and the leader of the Gorons living up on Death Mountain, gets a town that makes sense: Mountain Town of Darunia. And unfortunately, I don’t have great theories for how any of these characters get their names, though I was amused to point out that Rauru, the sage of light, has a name that is rendered in katakana as ラウル, which is also how you’d render the name Raoul. I don’t know why, but I think it’s funny for this exotic-sounding, wizard-looking character to be named Raoul. And then that little bully Mido also somehow gets a town named after him, but at least it’s an unremarkable one. To this day, we have no idea whom Kasuto is named after, but I guess since it’s a hidden town that sort of checks out.

Is it widely known that excluding Impa and the shrine monks, Sheikah characters in the Zelda series are generally named after fruit? I’m not sure I knew this before working on this post, but it’s apparently true. Paya = papaya. Pura = apparently apple but it’s complicated? Robbie = strawberry. Dorian = durian. Symin = persimmon. Cado = avocado. Steen = mangosteen. Granté = pomegranate. Lueberry = blueberry. Koko = coconut. Mellie = melon. Nanna = banana. Lasli = apparently raspberry? Cottla = apricot. Olkin = pumpkin. Cheria = cherry. Ollie = olive. Trissa = citrus.

Similarly, all the Koroks are allegedly named after trees — and I must say that makes a lot more sense than the Sheikah being named after produce — but the fact that Wind Waker identifies the Koroks as the evolution of the Kokiri is another example of the linguistic evolution/mutation that this series does in order to connect new things to previous games. Yeah, I can imagine that the name Kokiri might morph into Korok over time. Sounds shift about and end syllables get chopped off. Anyway, this list was a bit harder to put together since some of them are obvious — Rown is a rowan tree, Hollo is a holly tree — but others are more obscured. Hestu, for example, is apparently a chestnut tree, but I don’t think I would have guessed that on my own. I’ll leave this detective work to someone more keen on Koroks, I guess.

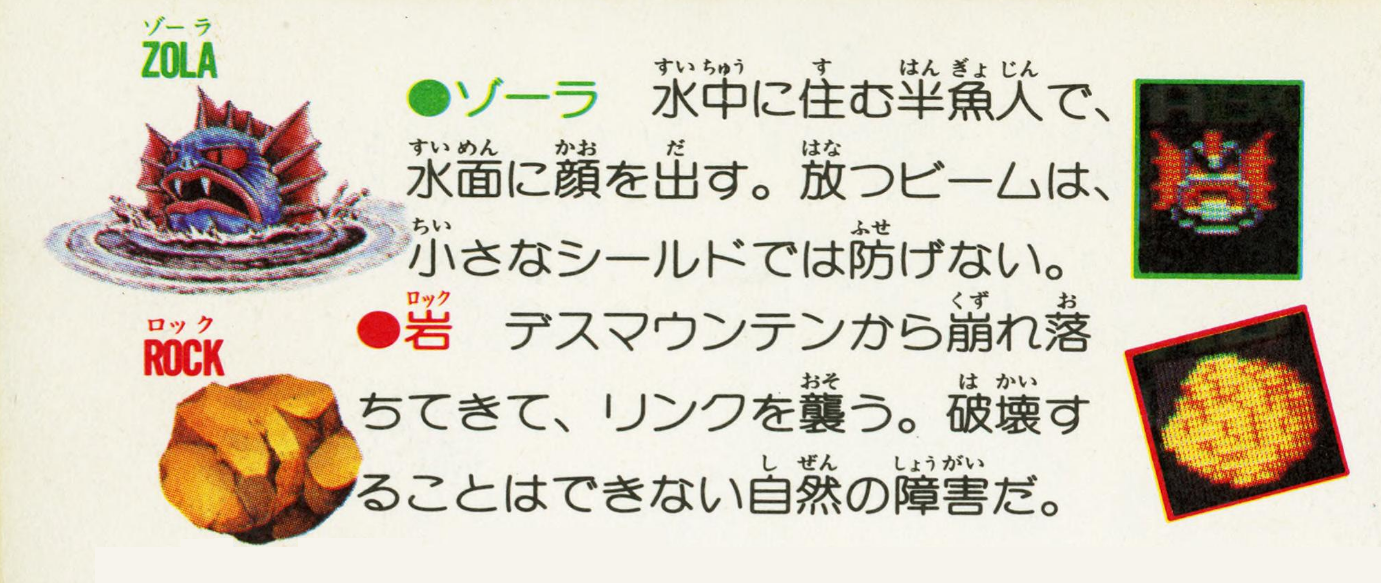

Back in the day, Zora’s name was rendered in English as Zola frequently enough that this is how I knew the character. I probably got this from the DiC cartoon, but I’m pretty sure it got it from the Japanese version of the instruction manual, which renders the monster’s name in romaji that way.

The first official Nintendo art of the Zora (labeled Zola), along with everyone’s favorite original Legend of Zelda monster, Rock (later renamed Goron). Via archive.org.

But the cartoon at least consistently referred to the scaly, monstrous merpeople as Zola and not Zora.

In the episode “The White Knight,” you hear Link specifically address the fish monster as Zola, not Zora, at the 2:38 mark in this clip. Am I including this to prove my point? Sure. But I’ll also mention that my podcast covered this for a Patreon episode that I’ve now made so it can be listened to for free. Yes, we have theories about the choice to call the title character a fop and a braggart.

Once the “new” Zora were introduced in Ocarina of Time, Nintendo chose to standardize all of them, hostile and friendly alike, as Zora, and I guess I can see why this made sense from a branding perspective. But applying Zora to one group and Zola to another would have actually been a halfway decent workaround, at least for English-speaking audiences. That’s not what happened, and the first time I saw new and old styles interacting was just recently, in Echoes of Wisdom, which instead differentiated the “classic” ones as River Zoras and the new ones as Sea Zoras, which I suppose makes more sense.

Finally, in trying to find other possible Hylian roots, I did come upon some interesting bits relating to Zelda names, mostly belonging to monsters. Here’s what I thought was interesting, save for a few items that I decided to save for their own posts down the line.

Echoes of Wisdom reminded me that the generic snake enemy in the Legend of Zelda series is named Rope (ロープ or Rōpu). Even though the similarities between a snake and a length of rope are fairly obvious, it nonetheless has always struck me as strange that this is a thing, just because I can’t think of other recurring enemies that are essentially equivalent to a real-world creature but named after an ordinary object. For example, the bats in Zelda games are Keese (キース or Kīsu), even though they’re basically just bats, not that I can make anything of that game. Given how generative Dungeons & Dragons is for other fantasy game series, I wondered if maybe the Roper monster could be what gave the Zelda snake its name, but no, I think it really is just as simple as the fact that snakes look like rope, more or less. Unless I’m missing something?

Another recurring enemy introduced in the first Legend of Zelda is the Peahat (ピーハット or Pīhatto). Later games style them to look more botanical or outright floral, but in the original game, they really look like propeller beanies, and I wondered if their name could result from this style of hat being referred to as a P-hat, kind of in the style of the P-Wing from Super Mario Bros. 3, either in Japan or anywhere else. As near as I could tell, this is not a thing, and I therefore have no idea where the Peahat got its name. And from what I could find online, no one else has put out any other theories either.

Zelda II introduces a beetle-like enemy called the Lowder (ローダー or Rōdā), and according to a 2015 article in the A.V. Club, this thing is named after Greg Lowder, a former Nintendo gameplay counselor. Lowder’s version of the story states that it was a kind of joke:

Whoever did this one did it to insult me, because the description of it was all “slimy creature.” I’m like, “You know what? There’s now a creature in The Adventure of Link named after me, so I really can’t argue with that too much.”

I’m curious how true this actually is, because the Japanese name was already very similar to Lowder’s name, so either the original Japanese team named it after him or the person who was doing the localization noted how close the katakana was to Lowder’s name and then spelled the English to match. This particular creature did not ever appear again, but Zelda II also features a scorpion enemy called the Aruroda (アルローダ) whose name would seem to be based off Lowder’s Japanese name, and this creature actually did appear in Echoes of Wisdom. If the story is true, then I guess Greg Lowder’s legacy lives on.

One of the palace bosses in Zelda II is a long-necked dragon that emerges from one of three lava pits to attack Link. This creature’s name in the English localization of the game was Barba, which would seem to be a shorter version of the original Japanese name, Barubajia (バルバジア). This creature actually made a second appearance as a boss in Ocarina of Time, as the boss of the Fire Temple, Volvagia (ヴァルバジア). For reasons I explain in the Sypha Belnades article, there’s a fluid relationship between the B, P, F and V sounds when translating between Japanese and English, and as a result the fact that these two dragon bosses are one in the same becomes hard to notice. It’s similar to how early translations of Final Fantasy IV referred to Barbariccia as Valvalis.

Again, not counting a few additional Legend of Zelda-related posts I have planned for the future, that’s all I’ve got for you, which means that a lot of monster names introduced in the original game are unexplained as of yet. Maybe they always will be, but if you’re reading this and have an etymology or even a theoretical etymology for Dodongo, Ghini, Gibdo, Gleeok, Goriya, Lynel or Tektite, please let me know. Wallmaster I think I’ve got, at the very least.

Link and Zelda vs. a Lanmola, a Darknut, two Gibdos, some Keese aand what I’m guessing is an early version of Ganon that is not yet all that pig-like, via Legend of Zelda.