Who Put the ‘P’ in the P-Wing?

It’s one of Super Mario Bros. 3’s most valuable items for people who are bad at video games.

It’s the P-Wing. And it’s hiding a connection to the Mario series lore that’s not obvious in the western localization. This is weird because Super Mario Bros. 3 seems to be largely about bringing that lore to the forefront, commenting on it, and asking the player, “Hey, can you appreciate this lore we’re throwing at you?”

Regardless of which version of Super Mario Bros. 2 you got in your part of the world, Super Mario Bros. 3 showcased Nintendo’s desire to get past the previous game and instead return to the original, to grow and evolve the elements that made it great. It’s not just a harder version of the original Super Mario Bros., like the Japanese sequel was, and it’s not something that ditches those play mechanics for something altogether different, like the western sequel did. It’s something that loves that first game, to the point that it’s already showing reverence for it and treating the stuff introduced in that game like it’s important. It’s playing with its own canon, basically.

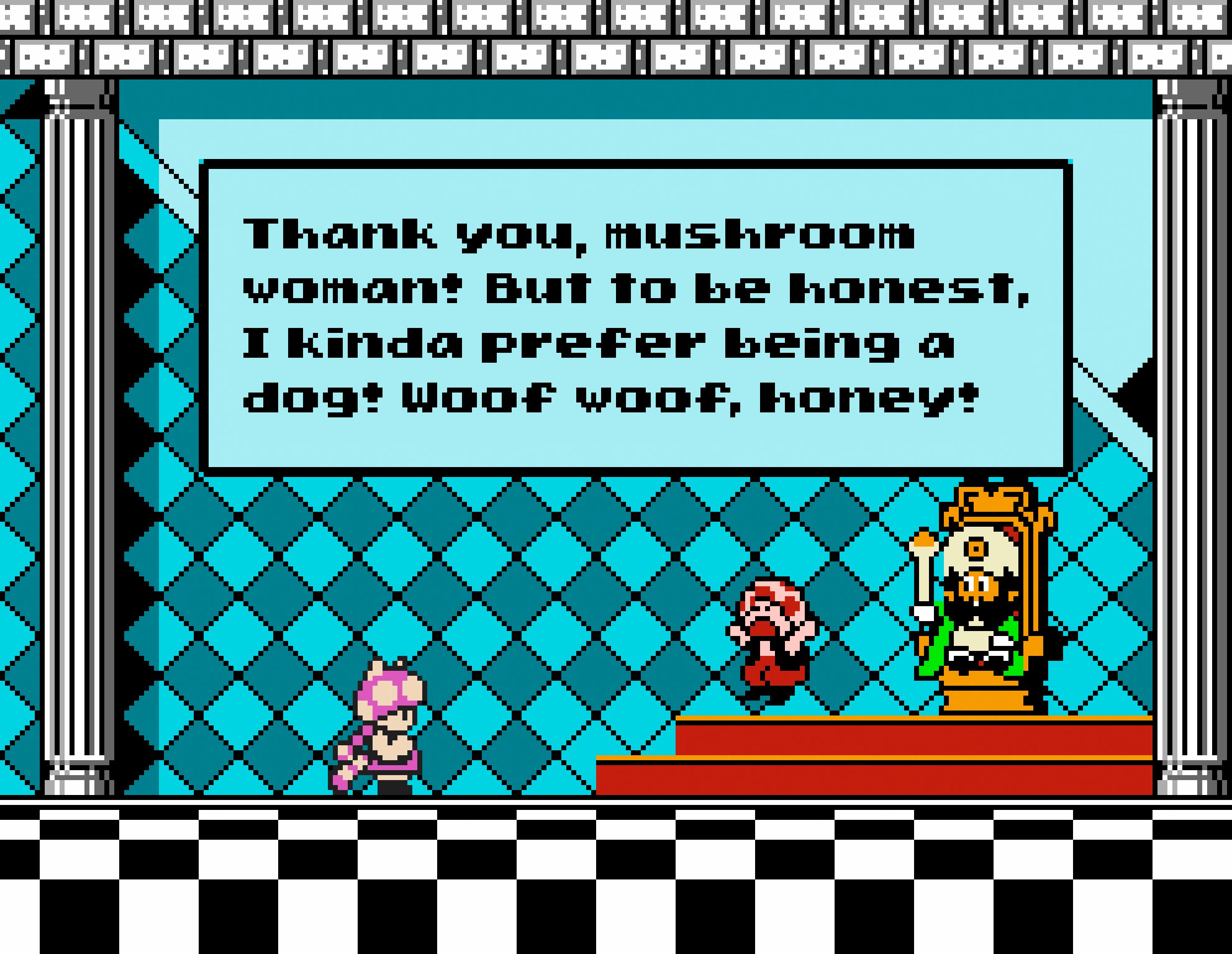

I’d imagine that a lot of players’ go-to example of Super Mario Bros. 3 looking back at the series so far would be the joke that Peach delivers upon being rescued. She’s making fun of the infamous dialogue that Mario receives in the first game after he beats a lesser Bowser and rescues what turns out to be not Peach.

While this is a great example of this trend, it’s one that exists in the western localization only, even if the “Thank you, Mario! But our princess is in another castle!” message was in both Japanese and English versions of the original game. In the Japanese ending to Super Mario Bros. 3, Peach just thanks Mario without jerking him around, saying (in Japanese), “Thank you! Finally, peace has returned to the Mushroom World. The end!” Yeah, it’s way less fun.

An example that’s in all versions of the game would be its newfound interest in making power-up items out of the enemy characters that appeared in the first Super Mario Bros. game. Most obviously, there’s the Hammer Suit. In addition to the Frog Suit and Tanooki Suit, Mario can dress up like the Hammer Bros. (ハンマーブロス or Hanmā Burosu), the hammer-tossing Koopas that bedeviled many a tentative player trying to get through the original game. Using this power-up, Mario gets the ability to throw hammers at enemies and even gets a shiny black shell that he can use to deflect fire attacks, which is something the Hammer Bros. themselves never had.

If we are being nit-picky about series lore, the Hammer Bros. in Super Mario Bros. 3 do, in fact, have black shells and helmets, but I feel like this power-up might also be referencing a different Mario enemy. (See the miscellaneous notes section.)

Thus, the Mario Bros. get to take on the powers of the only other pair of siblings in the original game. Honestly, it never occurred to me until I wrote this post that the Hammer Bros. are supposed to be a mirror of sorts to the Mario Bros. in that they come in pairs and they’re wielding the weapon that used to be Mario’s back in Donkey Kong. That’s some nice symmetry there, Nintendo.

The Hammer Bros. are not the only enemies to generate an item, however, though the next two I mention wouldn’t be as obvious to people playing in the localized western version of the game. One of the items that Mario can use on the map screen in between levels is the cloud belonging to Lakitu, the little punk who in the first game throws eggs that hatch into Spinys. In SMB3, the item allows Mario to move past a stage the player would rather skip, much in the way Lakitu’s cloud would allow him to stay above the fray in an actual stage.

Oddly, the English instruction manual for the game doesn’t identify the item in a way that doesn’t make the reference to Lakitu clear, because it calls it Jugem’s Cloud — clearly a direct translation of the Japanese name, ジュゲムの雲 or Jugemu no Kumo.

In Japan, Lakitu’s name is Jugemu (ジュゲム), presumably a reference to a Japanese folktale about a boy with an absurdly long name. The first part of his name is Jugemu Jugemu (寿限無 寿限無), which translates to “limitless life,” which I can only suppose would be assigned to this Mario character because he is persistent and, unlike other enemies in the game, will eventually return if defeated. For the record, I haven’t got a clue where this character’s western name might come from. If Clyde Mandelin also doesn’t know the etymology of Lakitu, I’m assuming the answer is lost to time, though if you have a clue, please speak up.

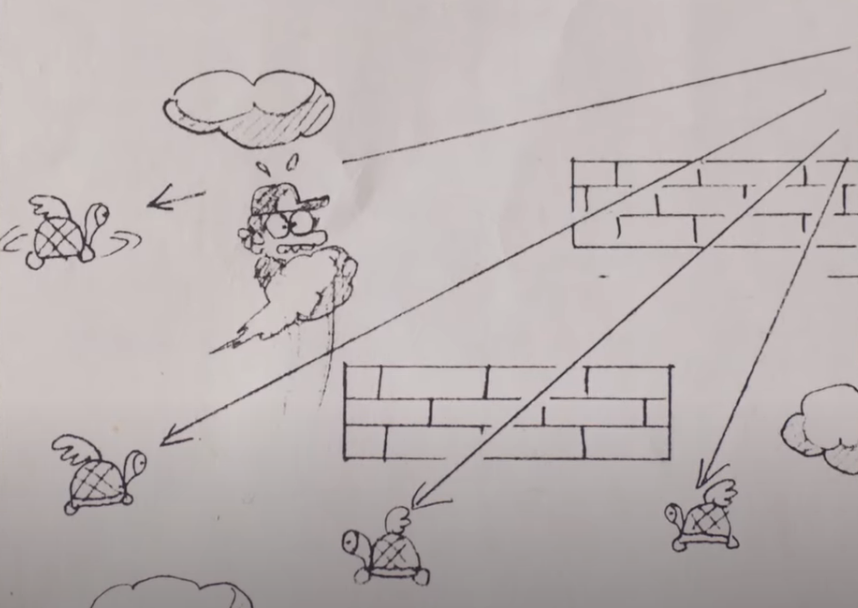

Since the early days of the original SMB, there has been the notion of letting Mario ride around in a cloud, if not specifically Lakitu’s cloud. In this video — a joint interview of the game’s creators, Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka, on the occasion of the the thirtieth anniversary of the game — they show sketches for how it could have worked. (Miyamoto said no, it turns out.)

It would be finally realized in Super Mario World, where Mario can knock Lakitu out of his cloud, climb into it and use it to cruise around the sky, but I’d bet a lot of non-Japanese players wouldn’t have made the connection that something kinda sorta similar existed in Super Mario Bros. 3 as well, just as a result of the name chosen for the instruction booklet. Perhaps the person localizing the manual didn’t recognize Jugemu as being the Japanese name for Lakitu and just thought it was a different character?

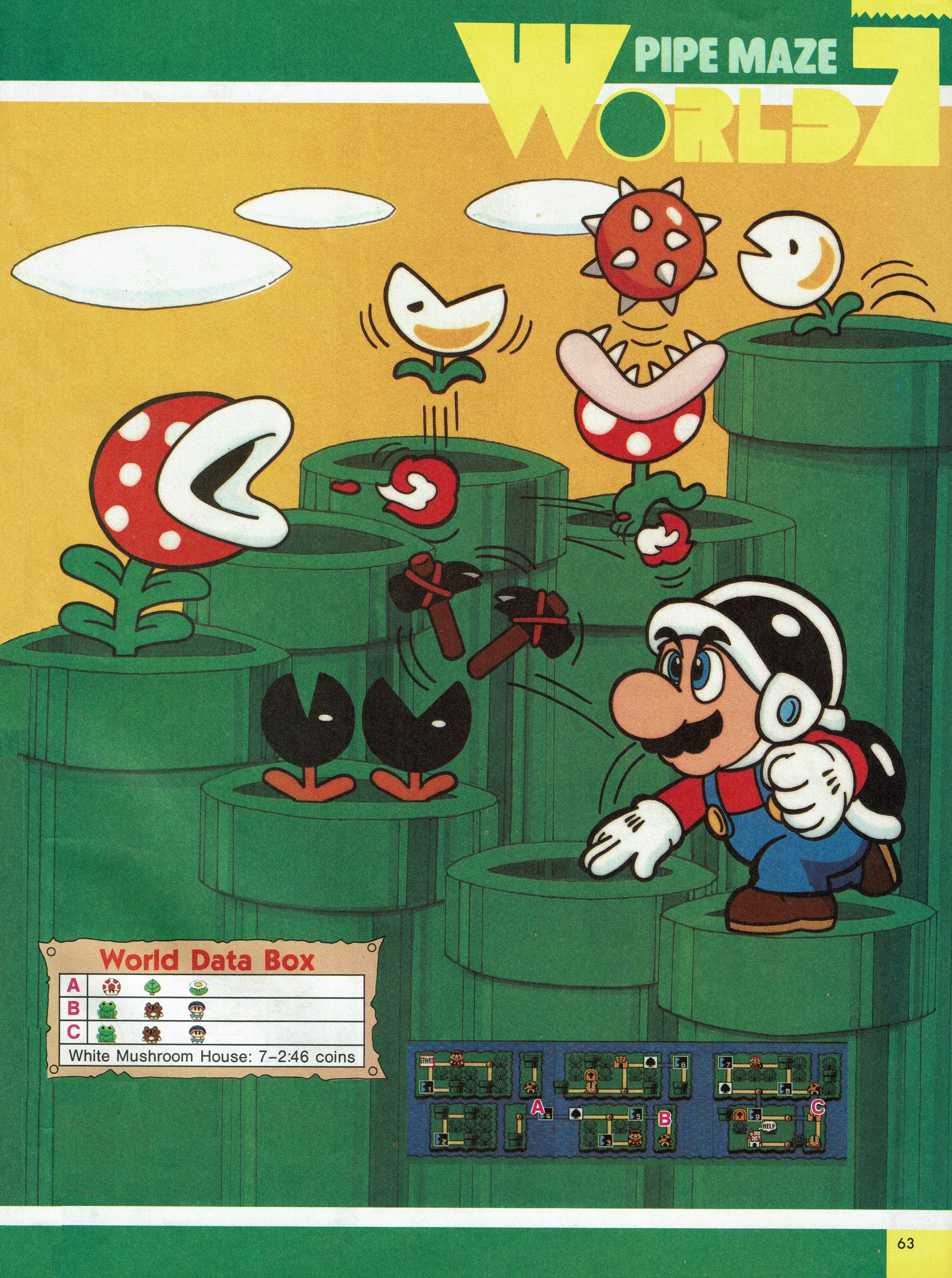

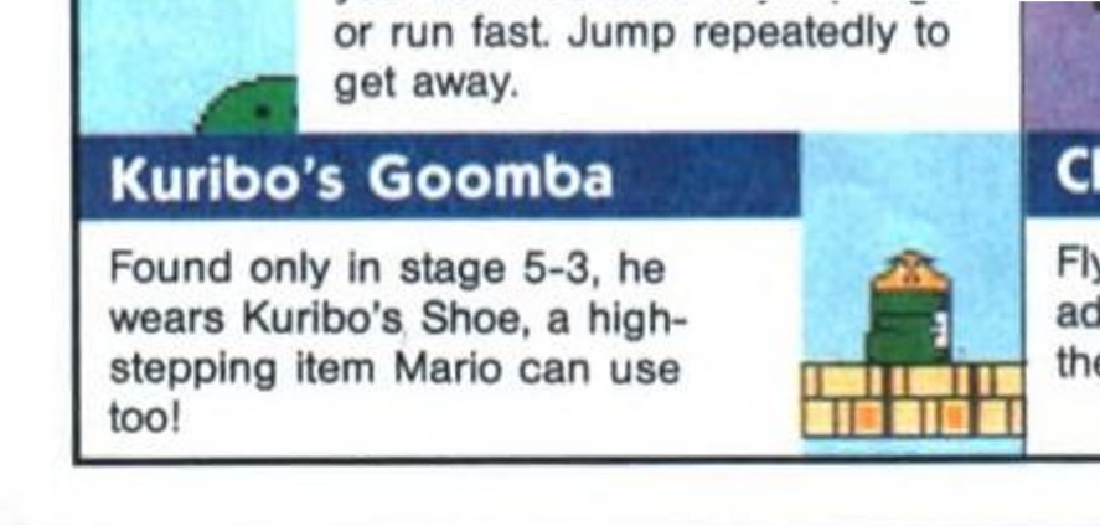

Whatever the case, something similar happened with another item in the game: Goomba’s Shoe, which isn’t mentioned in the instruction booklet but which the Nintendo Power official strategy guide for Super Mario Bros. 3 refers to as Kuribo’s Shoe, Kuribō (クリボー) being the Japanese name for the Goomba. (The Japanese name implies that Goombas are chestnuts and not mushrooms, and it’s complicated enough that I gave the matter its own post, not that it will resolve the confusion.) Goomba’s Shoe is one of the rarest power-ups in a Super Mario game, appearing only in Super Mario Bros. 3’s level 5-3 and not appearing in another Mario game until Super Mario 3D World, as an ice skate. Two years after that, it would become a core element of gameplay in Super Mario Maker, in both wind-up boot and stiletto heel variations.

The fact that this would translate as “Goomba’s Goomba” makes me think the translator wasn’t aware what Kuribo meant.

To this day, I have no idea why the boots have wind-up keys.

This item works somewhat differently from the rest in that it’s just not as available, for one — you can only get it in this one level, and you can’t score a random one from a Toad House, where you can get most other power-ups. If Mario beats the level wearing Goomba’s Shoe, he won’t have it in the next level. But it’s also different in that the shoe wasn’t associated with Goomba before level 5-3; Mario wasn’t scoring a thing that was long associated with Goombas so much that he was just stealing a thing Goombas has just discovered in this one level. No, when it comes to the one last item that Super Mario Bros. 3 offers up to Mario as an iconic enemy thing he can use for himself, it’s actually the P-Wing.

Now, “P” is a powerful letter in the Mario series. Super Mario Bros. 3 also introduces the P-Switch, the magical item that temporarily turns coins into blocks and vice-versa, and while I’d venture a guess that the “P” stands for “power,” I can’t actually find any proof of that online. (In the Japanese instruction booklets for Super Mario Bros. 3 and Super Mario World, it’s identified as the Switch Block — スイッチブロック, or Suicchi Burokku, and the “P” goes unexplained.) Then in Super Mario World, Mario got a new power up in the P-Balloon, where the “P” apparently *is* short for “power” — the Japanese name is パワーバルーン, or Pawā Barūn — even if all it does is inflate Mario and make him float upwards like a helium balloon.

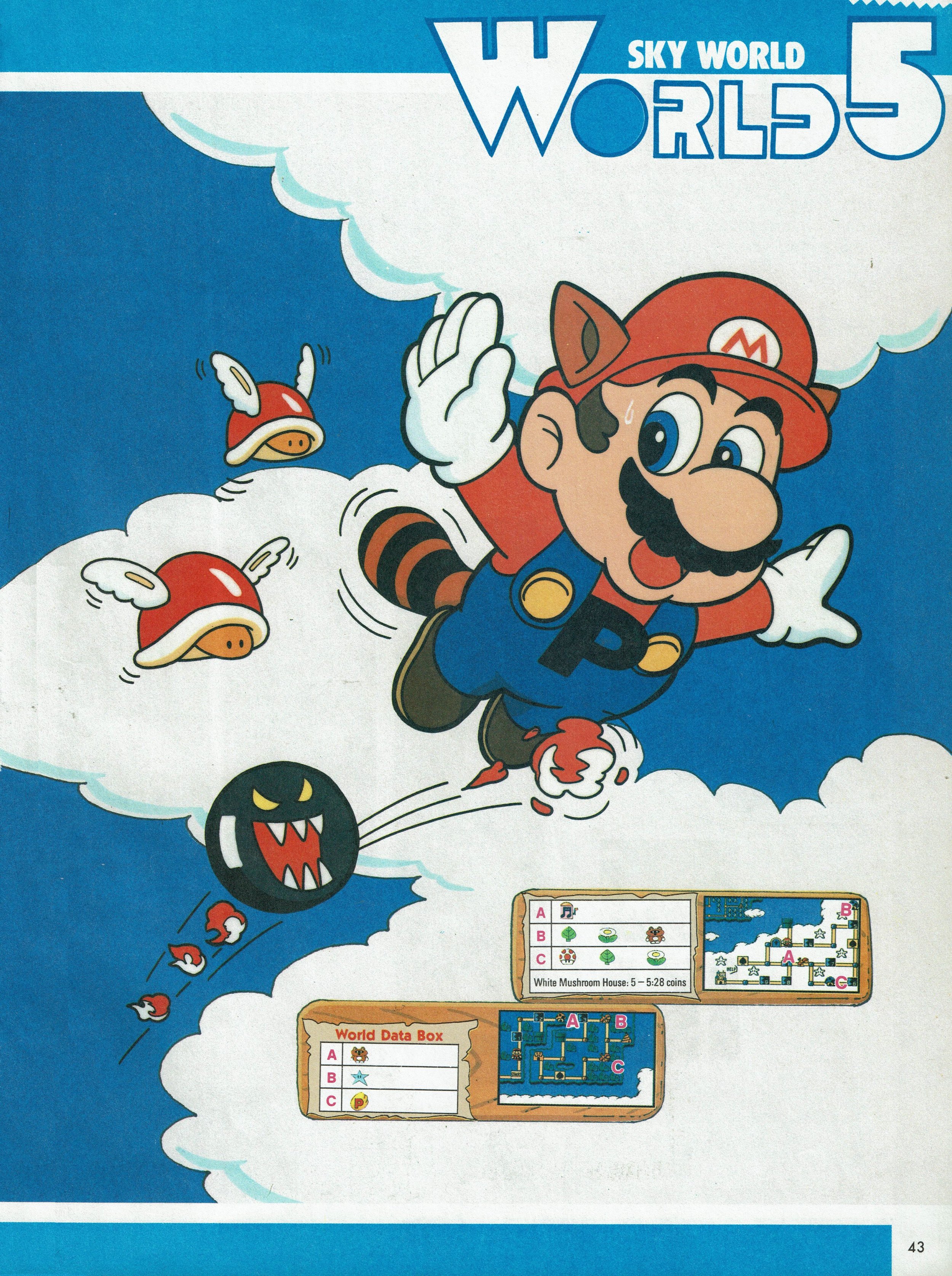

In the case of the P-Wing, however, the “P” specifically stands for the name of a known Mario series enemy. In Japan, the P-Wing is known as the パタパタの羽 or Patapata no Hane — in English, “wing of the Paratroopa,” though because patapata is the Japanese onomatopoeia for the noise of flapping, it could also be interpreted as “the wing that flaps,” which is not inaccurate, exactly, but it seems more likely Nintendo is alluding to the specific character and not using patapata in the general sense. In the original game, the standard version of the Koopa Troopa just scuttles along the ground. The Koopa Paratroopa, however, can either take giant bounds toward Mario or just fully hover in the air, though either reverts to a regular Koopa Troopa if stomped. Similarly, using the P-Wing only grants Mario the ability to remain airborne so long as he doesn’t take a hit. If he does, he’s stuck back on the ground, like the Koopa Troopas. So it’s really just Mario taking the Paratroopa’s wing and using it to give him limitless powers of flight, even if he’s not actually growing wings and instead using the raccoon tail to stay in the air.

Mario doesn’t grow wings, but he does get a “P” on his chest, though for the map screen only and never in the actual levels.

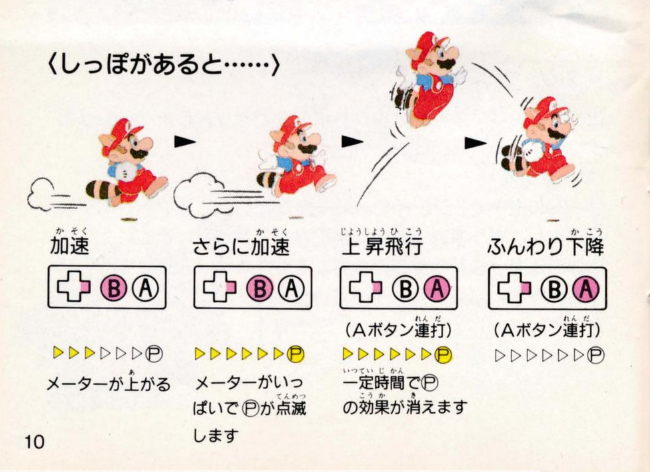

You’d be forgiven for assuming the “P” in P-Wing also stands for “power,” however, because the way the flight mechanic works in Super Mario Bros. 3 is that Mario must run a certain distance to charge his P-Meter. If fully charged (and if Mario is wearing the Raccoon Tail or Tanooki Suit) jumping will make Mario take off into the air. So what does the “P” in P-Meter stand for? “Power,” obviously. The Japanese instruction manual refers to it as パワーメーター or Pawā Mētā, literally “Power Meter,” even if the same document also refers to it as the Pメーター or P Mētā.

The bottom most text calls it パワーメーター or Pawā Mētā.

Again, I’m not sure why the English version of the game makes it unclear that this item is an allusion to a thing from the first game that most players would understand. You’d think Nintendo would want players to understand that this new game was returning Mario to his roots instead of sending him in a weird new direction like the western Super Mario Bros. 2 did. It’s especially odd because in the case of Jugem’s Cloud and Kuribo’s Shoe, you could assume it was a translation error, with the localizer not realizing that the Japanese name already had an English equivalent. In the case of a P-Wing, it wasn’t written in English as Patapata’s Wing but instead something that seemed to abridge the original name as much as possible, though perhaps whoever was in charge just saw that “P” and decided to keep it simple.

In the English-language instruction manual for Super Mario Bros. 3, it’s actually called a Magic Wing, leaving the “P” that’s clearly visible all the more mysterious.

Notably absent from the manual? Any mention of the Hammer Suit, though Nintendo Power had blabbed about that one and it was not a surprise for me.

Later, the English version seems to have adopted the term P-Wing, with a recurring kart model in the Mario Kart games going by that name in both English and in Japanese, where it’s the P Uingu (Pウイング).

So what can we learn from all of this? Well, for one thing, localization is an extremely complicated effort, and companies can sometimes fail to standardize things from one side of the ocean to another and in certain cases even between two pages of the very same document. (Note from Translator Fatimah: “Just from personal experience, clients often don’t give translators glossaries or official spellings for things, and we just have to do our best. We’re frequently asked to write up our own glossaries or pray to some higher being that there is already an official translation for something online somewhere.”) That’s not a knock against anyone. In fact, there’s an upside to all of this: Back in the day, when I was a kid without internet and no research skills, I would just sit there and wonder how much more of the world of Mario games was out there waiting for me, as a thing to enjoy but also as a means of answering a lot of the questions I had.

Did this line of thinking make me expect that fun new characters named Jugem and Kuribo were about to be introduced to the main cast of the Mario games, and I’d love them and their adventures forever and ever? Yes. Was I disappointed that this was not the case? Also yes, but it was gratifying to find out all these years later how these pieces fit together, and I hope that maybe this has answered some long-running questions for someone reading this post.

The goal for this project was to look into the decisions that made these games what they are. In a dream world, I’d actually get to talk to some of these people one on one, to find out what their thinking was in coming up with a concept or reframing that concept for an English-speaking audience. And I am trying to make that happen, but until then it’s fun to play with the stray bits we do have to see how we can make them fit together on their own.

Miscellaneous Notes

Just because if I don’t say it, someone will point it out to me: Paratroopa is a play on paratrooper. In the latter, it’s short for parachute, but in the former it’s just being used to represent the fact that it’s in the air. As far as puns go, it’s not a bad one.

You could consider the P-Wing a successor to the original wing item, which appeared in the Hudson Soft-produced Super Mario Bros. Special, a sort of remake/remix of the original game released for the POC-8801 and Sharp X1 computers. Once collected, it allows Mario to “fly” briefly by swimming through the air. The game also features the Donkey Kong hammer. It’s pretty wild to watch in action, even if this game in general makes me feel like I’m on cold medication. Skip ahead to the 29:00 mark in the below video to see the wing in action.

In addition to the Hammer Bros. Suit, which allows Mario to toss hammers in-level, there is also, separately, a hammer item that allows Mario to break rocks on the map screen and access routes he can’t otherwise. It looks like the Hammer Bros. hammer. It’s not, for example, a reference to the Donkey Kong hammer. But it’s a weird bit of redundancy in the game’s item set, though, and having the Hammer Bros. Suit doesn’t allow Mario to break rocks on the map screen.

The shell part of the Hammer Suit allows Mario to deflect fire attacks, but that’s not actually something the Hammer Bros. can do. The recurring Mario series enemy that can do that? Buzzy Beetle, who also has a shiny black shell, to the point that I wonder if the Hammer Suit is allowing Mario to have the powers of multiple baddies. The Japanese name for Buzzy Beetle is メット (Metto or just Met, presumably from the English word helmet). That is interesting because there’s another iconic, recurring baddie with a very similar form, function and name: the thing in the Mega Man series variously known as Met, Mattaur or Mettall or in Japanese メットール or Mettōru. It’s a walking hard hat, which is more or less what Buzzy Beetle amounts to.

Other Mario enemies might also get their Japanese names from the name of Jugemu Jugemu, from the Japanese folktale about the boy with the long name. Part of his name is Paipo, Shūringan, Gūrindai, Ponpokopii, Ponpokonā, with Paipo being a kingdom in ancient China. In Japan, the eggs that Lakitu throws at Mario are also called Paipo (パイポ). The similarly spiked balls that enemies throw at Mario in various games are known as Shūringan (シューリンガン), named the king of this kingdom. Spiked Piranha Plant eggs that Lakitu throws in New Super Mario Bros. are Gūrindai (グーリンダイ), the queen of that kingdom. And a teenage boy and girl Lakitu in Paper Mario — Lakilester and Lakilulu, in the English version — are in Japan called Pokopī (ポコピー) and Pokona (ポコナ), the prince and princess of this kingdom. Which is to say that there is a profound connection to spike-covered things in this series and this folktale, but if there is a deeper meaning, it’s lost on me.

The soundtrack for Super Mario Bros. 3 offers almost entirely new music rather than variations on themes composed for previous games. The original Super Mario Bros. overworld theme, for example, exists only in-game as a sort of Easter egg when Mario uses the music box item. The one exception is the underworld music, which is a remix of the first game’s underworld music.

I would be curious to know why Koji Kondo decided to revisit his original composition. Whatever the reason, this is the single most prominent callback to the music from the first game, and it occurred back when it was less common practice to do this. Super Mario World, for example, doesn’t call back to any music from the previous games at all, save for an Easter egg hidden in Special World, although that’s maybe because Kondo was playing with the notion of reusing the same basic melodic structure again and again. Only with Super Mario 64’s Hazy Maze Cave theme does it become a series-wide rule that “this is what underground sounds like” and less so a specific callback to the first game. The invincibility theme and the “hurry up!” theme both get re-used in Super Mario Bros. 3, I should point out, but both are things you hear for a brief amount of time, as opposed to looping throughout the entire stage. That’s a difference that’s maybe significant only to me, but it seems like a worthwhile one, but I also think that even by SMB3, these are established “rules” in the sense of “this is what this sounds like.”

The fact that the magic flute melody is reused from Legend of Zelda, however? That’s indicative of Nintendo not just referencing Mario’s own series lore but instead establishing a company-wise canon, something that they’ve continually been building ever since. (The Japanese name for this item, フエ or Fue, can be translated as “flute,” “whistle” or “recorder,” and it’s also called this name in the original Japanese version of Legend of Zelda.)

There’s actually a noise that’s heard a lot more often in Super Mario Bros. 3 that calls back to a different non-Mario game. It’s the one you hear when Mario transforms by touching a power-up. It’s almost exactly the noise used in Mysterious Castle Murasame for when enemies materialize onscreen.

And although the reference would have been clear for Japanese players who experience this Nintendo title, it would have been lost on most everyone else, because Mysterious Castle Murasame was not officially released in the west until 2014.

Work on Super Mario Bros. 3 began in 1986, and the game hit shelves in Japan in 1988. It’s tough to say for sure, because we don’t have precise development timelines for every bit of Super Mario Bros. 3, but it’s entirely likely that Nintendo made the decision to borrow the Bob-Omb long before there was any notion of turning the game it originated in, Doki Doki Panic, into a Mario game. In the west, we think of the Bob-Omb being the one holdover from Super Mario Bros. 2 that made it into Super Mario Bros. 3, but it’s actually more likely that this was just another cross-series “borrowing,” in the style of the Piranha Plant boss in the original Legend of Zelda. Regardless, I maintain that the Bob-Omb is the element of Super Mario Bros. 2 most successfully integrated into later games, even with this timeline flub.

There’s one final example of self-referential humor in Super Mario Bros. 3, and that’s the map for the third world, which is variously called Water Land, Ocean Side, Island Land, Sea World or Sea Side. (So many names!) The royal castle exists far to the east side of the map, on a chain of islands that resembles the islands that form Japan, with the castle more or less being placed at Kyoto, home of Nintendo’s headquarters. The king, once restored to human form, looks a great deal like Mario, the implication being that Nintendo’s headquarters is the castle and Mario is the king of Nintendo.

This particular king is the one given the most prominence in official Super Mario Bros. 3 materials, as he appears in transformed form in the art showing the Koopalings’ airship.

Here, he looks somewhat like a frog, and in-game, he looks more like a turtle. He’s likely meant to be a kappa, a creature from Japanese folklore, so there’s probably some humor meant in the guy who looks like Mario being turned into something that sounds a lot like Koopa. But the Koopa-kappa connection is one I will explore in a later post.

Believe it or not, even with this overlong miscellaneous notes section, I still have more to share about Super Mario Bros. 3! Look forward to another post in the not-too-distant future about the callback to Super Mario Bros. 2 that is actually not that at all. Development timelines are weird!

Two sections from this miscellaneous notes section ended up spawning their own solo posts: one on the history of the Goomba and whether it’s a chestnut or a mushroom, the other on how Mario’s sprite for Super Mario Bros. 2 looks better than the one from Super Mario Bros. 3 because it was designed after.