There’s Super Mario DNA in Doki Doki Panic

The game originally known in Japan as Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic was never supposed to become part of the Super Mario series. It did anyway, and as a result, the game known in the west as Super Mario Bros. 2 has always fought the reputation that it didn’t really belong. It’s for this reason that my first posts on this blog specifically list off the ways in which characters and concepts from this game ended up recurring through the franchise to the point that arguments about Super Mario Bros. 2’s legitimacy ultimately stopped mattering. Like, you can insist that the game is somehow less than the other two in the NES trilogy, but Birdo is still playable in Mario Kart World, you know?

In this post, I want to do the opposite of those original two posts, more or less — not kick Super Mario Bros. 2 out of the canon but point out that Doki Doki Panic had a fair bit of Super Mario DNA in it from the get-go, hence why it was so easy for it to be positioned as part of the series outside Japan.

Detail from a 1987 phone card showing corporate synergy between Nintendo and Fuji TV but also putting Imajin and Lina next to Mario and Peach before Doki Doki Panic became Super Mario Bros. 2.

If I were more conspiracy-minded, I might point out that it’s a little too tidy that Nintendo had a more or less Super Mario-like game sitting around, ready to have Mario and his friends plopped into it. If there were concerns at Nintendo of Japan that the “real” Super Mario Bros. 2 — the sequel we in the west know today as The Lost Levels — either wasn’t that great of a game or at least was a joyless exercise that might alienate gamers abroad, then it might make sense to create a similar enough platformer starring characters that could not travel overseas because they were owned by a different company. (Doki Doki Panic was developed by Nintendo but published by Fuji TV as part of promotion for its Yume Kōjō ’87 event, for which Imajin and his family served as mascots. For more information on this, read this post.)

As it turns out, however, it really did just work out all that easily, or at least that’s what Howard Phillips told me some years ago. In his recollection, Phillips was the person who told his bosses at Nintendo of Japan that the official, Japanese-produced sequel to Super Mario Bros. would have killed off Mario’s growing popularity in the United States because its difficulty verged on cruel. Phillips’ objections kicked off a chain of decisions that ultimately resulted in Doki Doki Panic getting transformed into the western Super Mario Bros. 2, stripped of its original heroes but still retaining a certain “Arabian nights” flair that would go unexplained until this origin story became widely known.

The account that Phillips shared with me very closely matches one offered in Jon Irwin’s 2014 book recounting the history of Super Mario Bros. 2. As far as I know, this is the best and most detailed work of scholarship related to this game, and if I’m being fully honest, I am jealous that he wrote it and I did not. But I’m also glad he wrote it, because as it turns out, Irwin fills in some crucial details that link Doki Doki Panic to the Super Mario series even before Howard Phillips figures into this story.

Doki Doki Panic began with a tech demo that, unless I’m mistaken, has never been beheld by anyone outside Nintendo. I think it’s a 2011 Wired article by Chris Kohler that brought this bit of prehistory to light, at least in the west, and it reads as follows:

[The game] grew out of a mock-up of a vertically scrolling, two-player, cooperative-action game, Super Mario Bros. 2 director Kensuke Tanabe told Wired.com in an interview at this year’s Game Developers Conference. The prototype, worked up by SRD, a company that programmed many of Nintendo's early games, was intended to show how a Mario-style game might work if the players climbed up platforms vertically instead of walking horizontally, said Tanabe. “The idea was that you would have people vertically ascending, and you would have items and blocks that you could pile up to go higher, or you could grab your friend that you were playing with and throw them to try and continue to ascend,” Tanabe said. Unfortunately, “the vertical-scrolling gimmick wasn't enough to get us interesting gameplay.”

“The game was mocked up [so that] when the player climbed about two-thirds of the way up the screen, it would scroll so that the player was pushed further down,” Tanabe said. The game-design team led by Miyamoto was tasked with coming up with a game that used this trick of programming. But Tanabe and Miyamoto weren’t too hot on the concept. While the prototype featured two players jumping, stacking up blocks to climb higher, and throwing each other around, the technical limitations of the primitive NES made it difficult to build a polished game out of this complex action. And playing it with just one person wasn’t very fun.

“Miyamoto looked at it and said, ‘Maybe we need to change this up,’” Tanabe recalled. He suggested that Tanabe add in traditional side-scrolling gameplay and “make something a little bit more Mario-like.”

The keyword for this prototype, at least as far as this discussion goes, is “Mario-style,” which could mean anything as general as any old platformer or as specific as something that actually starred Mario. Irwin’s Super Mario Bros. 2 book characterizes it slightly differently — and in greater detail.

An early, in utero version of [Doki Doki Panic] began as a follow-up to their most successful yet: They were experimenting with a new Super Mario Bros. game. This one, however, would pay homage to the past, placing the goal not far down a horizontal path, but at the top of the level, just like Donkey Kong. Only this time, the world would extend beyond the top of the screen. Secret areas of Super Mario Bros. existed above the clouds, but were rare and a single level above the main path. This new game would continually ascend, mirroring this company’s confidence after a century of finding its way.

But when Shigeru Miyamoto and a young developer named Kensuke Tanabe looked at this prototype, they felt something was off. Two characters stacked blocks on top of each other to progress ever-upward, but the screen only moved in single jarring swoops, shifting up once you approached the top, so that you’d begin again near the bottom.

[...]

Developers were still learning the new hardware; this prototype had not been optimized fully, its code not efficient enough to render images in the same smooth, scrolling fashion as Super Mario Bros. And the gameplay just wasn’t that much fun. Miyamoto stopped the project before it could continue longer. But he gave young Tanabe an idea.

“Make something a little bit more Mario-like,” Tanabe recalls his boss telling him. The compromise called for a game including horizontal levels such as [Super Mario Bros.], but smaller sections of this new kind of vertical gameplay. Lifting blocks turned into pulling up vegetables as projectiles. What began as an experiment shifted into an amalgam of past successes with new ideas.

And that’s exactly what resulted. It’s telling, perhaps, that the first thing that happens in the game, whether you’re playing it as Super Mario Bros. 2 or Doki Doki Panic, is that you fall from the sky, sailing down for a full screen before you land on any type of platform. This opening highlights the exact kind of vertical scrolling that didn’t exist in Super Mario Bros., but it also serves as a reminder that this kind of movement is where this game first originated.

Irwin’s description doesn’t say that the demo’s two player-controlled characters were Mario and Luigi, though that would have made a lot of sense, especially considering the “everyman working any job” role fulfilled by Mario back in the day. But it does tie the demo to the Super Mario series more explicitly than Kohler’s use of the adjective “Mario-style” because it states that the demo was created in an effort to make “a follow-up” to Super Mario Bros. and “a new Super Mario Bros. game.” Neither of these necessarily implies a full-on sequel, I should note, but I think that may be beside the point. If Irwin’s characterization is accurate, then it means that the earliest version of the western Super Mario Bros. 2 began as something at least as close to a Super Mario game as, say, Wrecking Crew or any other old school Nintendo game that had Mario working some random, one-off job.

This changes the story considerably. Instead of the western Super Mario Bros. 2 originating as this rando Arabian fantasy advertainment video game that was just sitting around collecting dust until someone decided the “real” sequel was too difficult, you have Doki Doki Panic evolving more organically from a concept that was at the very least Super Mario-adjacent, if not a test-run for something that could have been the actual sequel.

That one mythical tech demo is not the only piece of evidence suggesting Super Mario DNA in Doki Doki Panic, but I think it’s both one of the most compelling and also one fans are least likely to know about. Depending on your perspective, however, the other evidence may be easier to refute.

For one thing, Doki Doki Panic features POW Blocks, which debuted in Mario Bros. and which shake the ground like an earthquake when struck or thrown. Their inclusion might seem like an obvious indicator of Super Mario DNA because the POW Block is very much associated with the franchise now. But I’m not necessarily sure it would have been read this way when Doki Doki Panic was first released in 1987. In fact, Doki Doki Panic is only the second appearance of these items in any Nintendo game ever.

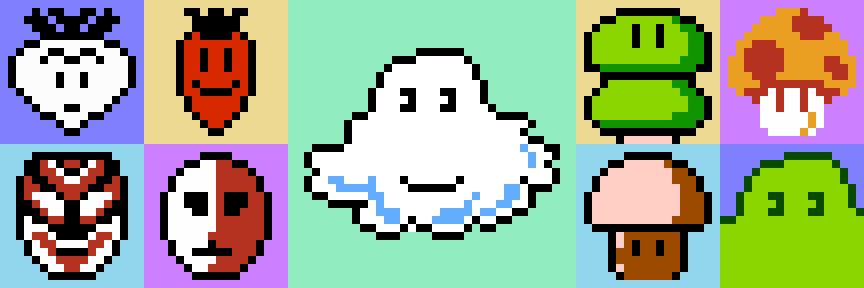

Clockwise from top-left: The POW Blocks from Mario Bros. (1983), Doki Doki Panic (1987), Paper Mario (2000) and Yoshi’s Island (1995). I don’t know how much you can shake up the design of a rounded square that says “POW” on it, but if anything, a lot of later Super Mario games use the red design from Doki Doki Panic, though many also use the original blue version too.

Aside from retreads of Mario Bros. appearing throughout the Game Boy Advance era, POW Blocks didn't start appearing regularly in Super Mario platformer games until New Super Mario Bros. Wii in 2009. In 1987, I think the POW Blocks showing up in Doki Doki Panic might be viewed more as one of the cute, cross-franchise cameos that Nintendo was doing early on, such as the Piranha Plant showing up as dungeon bosses in Legend of Zelda. Or it could be Nintendo devising an object that early on that wasn’t tied to any one game series, kind of like how the fire bars appearing in Bowser’s castle in Super Mario Bros. were originally designed as obstacles for Legend of Zelda.

Doki Doki Panic also features the power-ups that are variously known as Starmen or Super Stars or just stars, depending on what Super Mario game you’re playing. Touching these grants your character temporary invincibility in Super Mario Bros. and Doki Doki Panic both, even if the stars move around the screen differently in either game.

The Japanese manual for Super Mario Bros. calls it スター (Sutā), from the transliteration of the English word star, whereas the Doki Doki Panic manual just refers to it using the kanji 星 (hoshi, “star”), but this item gets called a lot of things in English and Japanese.

Now, items that give you the ability to bulldoze through enemies were common in platforming games, and I wouldn’t be surprised if another game also had a star as its version of this, but the way the Doki Doki Panic version has eyes makes it harder to dismiss this one as a more likely Super Mario reference.

In fact, there are faces throughout Doki Doki Panic and The Lost Levels both. The trend started off in a small way in Super Mario Bros., with cloud blocks that appear in coin heaven, and it continued for years, eventually reaching critical mass in the Nintendo 64 era. But it’s interesting that that Doki Doki Panic and The Lost Levels both double down on it. Someone at Nintendo clearly had some kind of fixation on making everything look happy at all times.

While some of the extra faces appearing in Doki Doki Panic are part of the game’s mask motif, The Lost Levels stuck them on items and background elements that hadn’t in the first game.

Another difference with the star is the music. In Super Mario Bros. 2, tagging the star means hearing a new version of the classic Super Mario star theme, but it’s not present in Doki Doki Panic.

But for what it’s worth, tagging a star in a Super Mario game doesn’t always get you the standard star theme. In Super Mario Land, for example, you hear the cancan song even if the star otherwise behaves normally.

I tend to write this off as just one of the many ways Super Mario Land tries to answer the question, but weird and different?”

At one point, I was going to argue that Doki Doki Panic borrows the jumping sound effect from Super Mario Bros. It’s so similar that it didn’t need to be changed when it became Super Mario Bros. 2, but I think this might just be how Nintendo decided that jumps should sound in platforming video games, Super Mario-affiliated or not. For example, the jumping noise in Ice Climber is virtually identical, even closer to the one from Super Mario Bros. than the one on Doki Doki Panic, but it’s not a sign that Ice Climber is any kind of Super Mario game.

But then again, there are more assets shared by unrelated Nintendo games than you’d think. The noise used in Super Mario Bros. 3 for the transformation into Tanooki Mario came from Mysterious Castle Murasame, for example.

Finally, the way Doki Doki Panic uses vases in many ways parallels the way Super Mario Bros. uses green pipes. You can enter both to search for goodies, and both sometimes have enemies popping out of them. But the more interesting, more specific parallel is that both games use them as part of their respective warp system mechanics. In Super Mario Bros., the various warp zone areas offer three pipes that lead to different worlds, and you enter the pipe you want to take. Doki Doki Panic also has you entering a vase to warp. It’s just not clearly demarcated where it’s going to take you, but at the very least entering a special version of the thing that normally just takes you underground seems notably similar.

If you have more examples of curiously Super Mario-style mechanics, graphics, sound effects or anything else happening in Doki Doki Panic, do let me know. It wasn’t until I wrote this piece that I realized that the ones that came to mind quickest were also the ones I could most easily explain away. But I think this mysterious block-piling tech demo is the best evidence in favor of putting Doki Doki Panic on the Super Mario family tree even before anyone had the idea to rework it into Super Mario Bros. 2. Sure, it might just turn out to prove that Nintendo was either nuts about Mario even then or that he was just the go-to guy to stick into any game you wanted.

Again, it’s not that Super Mario Bros. 2 needs much defending all these years later. Like I said before, Birdo is playable in Mario Kart World. At this point, she’s so much a part of the Super Mario games that it’s more notable when she’s not playable in a new spinoff than when she is. But in case you meet anyone in 2025 or beyond saying that Super Mario Bros. 2 doesn’t truly belong, send them this article and encourage them to study their history.

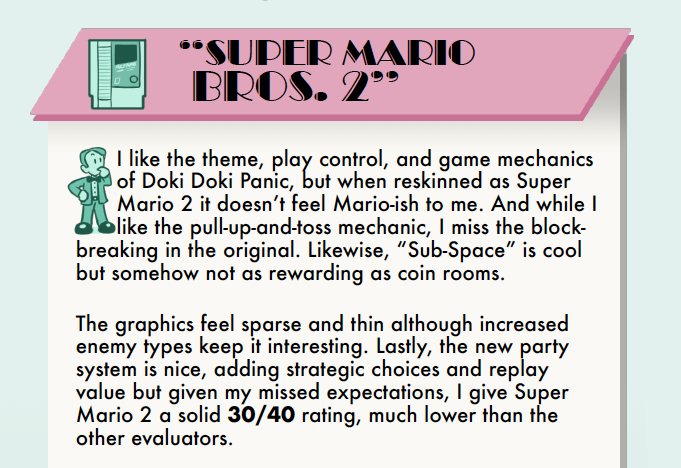

Now, I don’t need a reason to write about Super Mario Bros. 2. At this point, it’s the single game I’ve written about the most on this site. But in this case, I wanted to put something up as a means of also posting about how this past week, I was the guest on the podcast A Super Mario Moment, talking about this very game. Hosted by Hamish Steele, it exists in both video and audio forms, so if you think your experience would be improved by seeing my actual face make words, that option exists below.

As you can see from the key art, one of the topics we focus on is the innate queerness of this game, which manifests in Birdo, yes, but in a lot of other more subtle ways. Peach’s ability to hover in the air may make her the ideal player for beginning gamers who need extra help jumping from platform to platform, for example but she also allowed me and a lot of other little gay boys to play as a female character back when that wasn’t all that common. Super Mario Bros. 2 was actually the first game I ever beat, and I beat it for the first time as Peach, so I’m especially grateful for the unlikely series of events that ended up making this game part of the Super Mario series.

Would also recommend the Super Mario Odyssey episode with Drew Green, who happens to be the artist who made the Tanooki me art for my big piece on Birdo’s gender.

Miscellaneous Notes

As far as I know, the tech demo that became Doki Doki Panic has never seen the light of day, not even as part of the various leaks Nintendo has suffered over the past few years. If I’m wrong, however, please tell me. I would love to get my eyes on this one, just to discern for myself how much Mario is in it.

In reading various stories about how the western Super Mario Bros. 2 came to be, I was somewhat surprised to see Howard Phillips not get mentioned because it seems to me that his involvement is crucial. Had he not pointed out that the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2 kind of sucks, that game might have become the sequel here as well, and as a result, enthusiasm for the series might not have continued in the west and the whole of Super Mario fandom might have not remained a major factor in Nintendo’s continued success. For example, the Wikipedia page about Super Mario Bros. 2 doesn’t mention Phillips, and I would imagine that Jon Irwin’s book should be at least as reputable as the other sources cited on that page.

For what it’s worth, Phillips told me about his involvement in Super Mario Bros. 2 just during a regular conversation. I’m good friends with his daughter, food historian Katherine Spiers, and I met Howie, as Katherine calls him, an Indiecade in 2012. Of course, Super Mario Bros. 2 was the first thing I asked him about. I find it funny that in his book, Gamemaster Declassified, he actually admits to feeling like Super Mario Bros. 2 lacks the feeling of a true Mario game.

Also, in researching this specific topic, I came across quotes from Howard Phillips that don’t mention Jon Irwin’s book or the fact that this specific passage comes from the foreword, which Phillips wrote. Although I’ve clearly outed myself as a Super Mario Bros. 2 superfan, I have to say that Phillips eloquently describes why I prefer it to the “real” sequel.

My experience with [the Japanese] Super Mario Bros. 2 began in the summer of 1986 when I received a new box from Nintendo that contained yet another set of new titles for both the Famicom and the recently released Famicom Disc System. One of these Famicom discs was Super Mario Bros. 2. I was surprised that the disc had arrived at my desk without any fanfare or advance warning. After all, it was the sequel to the NES’s most popular game. I quickly loaded the game and began playing. What came next was completely unexpected.

I was immediately killed by a mushroom that, unlike the mushrooms in Super Mario Bros., was now poisonous. Chagrinned but undaunted, I continued playing only to be taken by a strong, unpredictable wind and tossed into a chasm. Soon after, I succumbed to the jaws of a red piranha plant that uncharacteristically rose from a pipe that I was already standing on — a platform that in Super Mario Bros. had always been safe. As I continued to play, I found that Super Mario Bros. 2 asked me again and again to take a leap of faith and that each of those leaps resulted in my immediate death. This was not fun gameplay, it was punishment — undeserved punishment.

I put down my controller, astonished that Mr. Miyamoto had chosen to design such a painful game. It was only later that I came to understand that Mr. Miyamoto had handed off most of the design responsibility of Super Mario Bros. 2 to other Nintendo staff. Apparently, during the year prior to the Japanese release of Super Mario Bros. 2, Mr. Miyamoto had focused most of his energies on the design of future hit The Legend of Zelda.

Amazed at how dark and punishing the supposedly entertaining Super Mario Bros. 2 was, I immediately shared my thoughts with Mr. Arakawa. In his typical stoic manner, Mr. Arakawa simply acknowledged my comments. By this time, I was well aware of the cultural differences within Nintendo that made bad news known but rarely discussed.

Yeah, “undeserved punishment” hits the nail on the head pretty squarely. Do go read Irwin’s book, BTW. It’s very good.

I wanted to check the staff credits to see if it’s true that Miyamoto had more to do with Doki Doki Panic than he did with the game we refer to in the west as The Lost Levels, and I was surprised to learn that I couldn’t do that. Rather cryptically, this is all that’s written on the Super Mario Wiki page on the subject:

Like the original Super Mario Bros., Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels does not feature a staff roll or any sort of credits. Unlike its predecessor, however, very little has been written about the game's development, leaving its precise staff composition a mystery. In a promotional interview for the NES Classic Edition, the game is referred to as Takashi Tezuka's directorial debut.

Miyamoto was credited as the producer for Doki Doki Panic, for whatever that’s worth.

It seems like a safe assumption that because Imajin, his family members, Lina and their pet monkey were created as mascots for Fuji TV’s Yume Kōjō ’87 event, Nintendo wouldn’t have owned the rights to them, hence why they’ve not shown up in any subsequent game. Kohler’s piece in Wired sort of implies otherwise, with Tanabe saying that Imajin’s crew just wouldn’t have been well-received in the U.S.

“I remember being pulled over to Fuji Television one day, being handed a sheet with game characters on it and being told, ‘I want you to make a game with this,’” Tanabe said.

Released in 1987, Doki Doki Panic was one of the biggest hits on Nintendo’s Disk System,

System, a floppy drive that worked with the Japanese version of the NES. Since this hardware was not released in America, many Disk System games were ported to standard game cartridges for U.S. release.

“Because we had to make this change, we had the opportunity to change other things” about the game, said Tanabe. “We knew these Fuji TV characters wouldn’t be popular in America, but what would be attractive in America would be the Mario characters.”

As far as I’ve ever seen, none of the enemy characters from Doki Doki Panic appear in any of the festival’s promotional materials, and they’re all there in all versions of Super Mario Bros. 2. What’s weird about the Yume Kōjō ’87 is that one of the main visual motifs was masks, and that is very much present in Doki Doki Panic and Super Mario Bros. 2, but I guess since the masks in question are based on various real-world cultural traditions, that’s not the kind of thing that you can legally own. But it is interesting to think about all the masks in the game as being a vestige of Yume Kōjō ’87 that did make the transition, leaving kids like me to wonder what was up with all that until I finally learned.

And finally, was I very excited to see that Phanto was making a long-overdue return in the Switch 2 version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder? Yes. Yes I was.

Phanto is such a great concept that I’m surprised the greater Super Mario series hasn’t made better use of it in all these years. I still feel just thinking about grabbing a key and seeing that creepy mask shake to life and then chase after me like Michael Myers. He can pop out of any corner of the screen. What a monster. What a pleasing terror.