The Legacy of Super Mario Bros. 2

To promote the 1991 release of Super Mario World, Nintendo Power magazine released its Mario Mania guide, not only to help players conquer the fourth console Mario game but also to celebrate Nintendo’s mascot, from his inception for Donkey Kong to his debut in the 16-bit generation. It is this publication that informed many Mario fans that the game we westerners called Super Mario Bros. 2 was, in fact, not the same sequel that players in Japan got. As a result of his growing awareness, there began a belief that our SMB2 was a vegetable-plucking, vegetable-chucking imposter, somehow less authentic than the first and third Mario games.

I vividly remember reading in the guide how Super Mario Bros. 2 was “originally developed in Japan as a game called Doki Doki Panic with a completely different cast of characters.” That’s it, along with a single screenshot of the first stage of the game, featuring a yellow fellow where I’d only previously seen Mario and his friends. This information set my nine-year-old brain on fire, frankly, because SMB2 was by far my favorite game, and the knowledge that other, “different” characters once populated it and were therefore Mario-adjacent just made me want to know everything about them. The internet would, in time, tell me everything I needed to know, but interacting online would also eventually introduce me to other Mario fans who treated SMB2 as a sort of black sheep — or, if you will, a poison mushroom or spoiled turnip — that didn’t deserve to be held on the same level as every “proper” sequel that came after it.

An inset on page 21 of the Mario Mania guide

That is a bias that has receded in recent years, perhaps because institutions tend to gain respect over time but also perhaps because objectors have since realized that the Japanese sequel, the game we in the United States would come to call The Lost Levels, isn’t a perfected piece of standard Mario “hop and bop” gameplay so much as a retread of the original game made more frustrating and cruel.

Or perhaps I’m projecting. I am, I should say, very much so biased in favor of Super Mario Bros. 2.

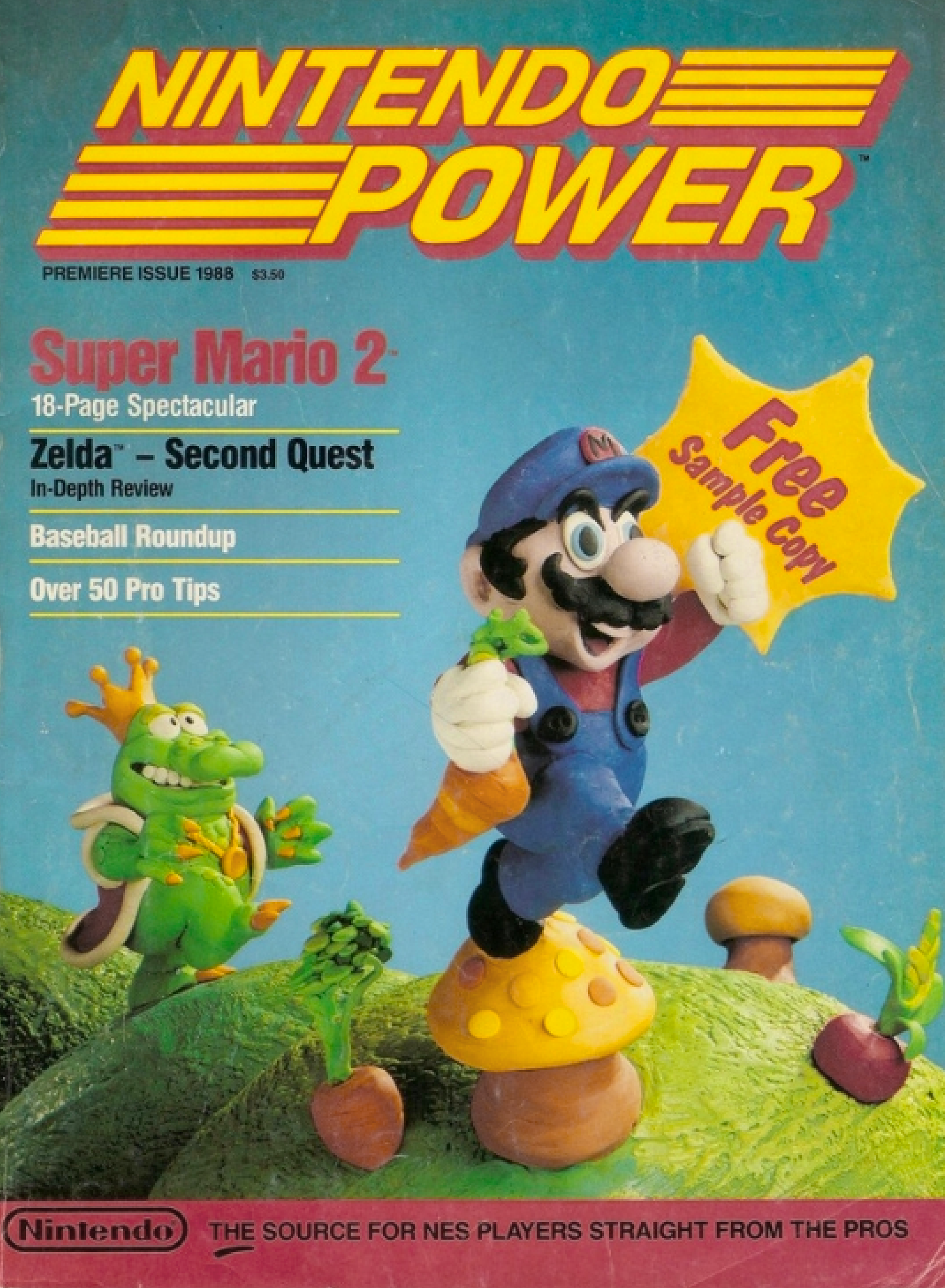

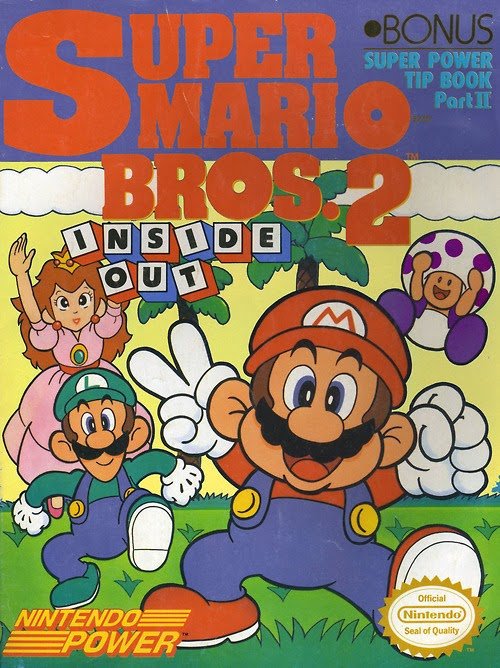

Shortly following SMB2’s release in the United States on October 9, 1988, the many elements it introduced to the series were inescapable. Merchandise featured the versions of Mario, Luigi and the princess that you’d see in the SMB2 instruction manual, for example, Mario often leaping into the sky with turnip in hand. It was the clay-modeled SMB2 version of Mario that graced the first-ever cover of Nintendo Power, July-August 1988, and the first animated version of the game series released in the United States, The Super Mario Bros. Super Show!, featured Shy Guys, Beezos, and Tweeters as part of King Koopa’s army alongside the baddies introduced in the first game; Wart, SMB2’s big bad, was nowhere to be seen on the show.

If you’d been touched by Mario madness at the time, you’d have every reason to believe that those Super Mario Bros. 2 elements would remain part of the mythos for the foreseeable future, through the release of Super Mario Bros. 3 and Super Mario Bros. 4 and Super Mario Bros. 5. I sure did. But I was wrong, because Super Mario Bros. 3 saw a return to the style of the first game, including Goombas, Koopa Troopas, and Piranha Plants, and by the time Super Mario World was released, it seemed like the stuff of SMB2 would be gone for good.

It wasn’t, in the end, and I thought it would be interesting to see what did eventually re-emerge into the Mario series and how long it took to see them become regularly recurring in the games to come. This is a two-part post chronicling SMB2’s gradual return from… not obscurity, exactly, but at least from relatively less prominence.

Gameplay Elements

Not gonna lie, a lot of the things that technically debuted in Super Mario Bros. 2 and appeared again in Super Mario Bros. 3 or Super Mario World were mainstays of the platformer genre and would have made their way into the series even if Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic hadn’t been retrofitted into a Mario game. These include ice levels, desert levels, themed levels in general, quicksand, spike traps, conveyor belts, vertical scrolling, horizontal backtracking, keys you’d need to unlock doors, life meters, and bonus games as a means to earn extra lives.

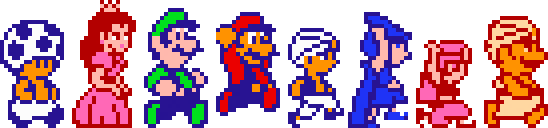

Perhaps the game’s most distinctive feature — the option to play as characters who were not Mario, each with their own abilities and shortcomings — would not be featured again in a standard Mario game until the Nintendo DS remake of Super Mario 64, where you can play as Mario, Yoshi, Luigi, or Wario. For what it’s worth, Super Mario Kart games and Mario sports games starting with the 1995 Virtual Boy title Mario Tennis also allowed this, but there wouldn’t be a second Mario platformer with the option to choose from SMB2’s cast until 2013’s Super Mario 3D World, which is as close as a proper sequel as SMB2 has ever gotten.

Left to right: floaty but weak, jumpy but slippery, boring and boring, strong but heavy as a lead paperweight.

The other standout feature of the game, pulling vegetables from the ground and flinging them at enemies, would only rarely return. Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker features pluckable, chuckable turnips, and a mission in Luncheon Kingdom in Super Mario Odyssey has Mario carrying giant turnips above his head, SMB2-style. Notably, there are certain e-Reader levels made for Super Mario Advance 4 that feature SMB2-style vegetables, but these levels featured the return of elements from other Mario titles as well, in the way the NES Remix games exist specifically to make a mad jumble of Nintendo nostalgia.

Oddly enough, there is some presence of this projectile mechanic in 2014’s Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze, where the plucking and chucking of enemies and items is central to the gameplay. By his own admission, this is a result of Kensuke Tanabe, director of Doki Doki Panic, serving as producer of both Donkey Kong Country Returns and Tropical Freeze. It’s worth noting also that Tropical Freeze, like SMB2, features four playable characters, each with their own physical attributes. It’s also worth noting that Tropical Freeze and Super Mario 3D World were released for the Wii U in the span of less than three months, as if Nintendo just suddenly realized in 2013 that Super Mario Bros. 2 is a game that exists and some players might want to revisit.

Vegetable-plucking also exists as part of Peach’s moveset in the Smash Bros. series, though that’s hardly the only thing she inherits from SMB2. Her ability to hover in midair exists in the Smash games and also in Super Mario Run and Super Mario 3D World as a callback to the original game. Technically, she can also hover or float in Super Mario RPG, Super Princess Peach and Super Paper Mario, but in those games it seems like she’s doing that with her umbrella, Mary Poppins-style, and not under her own power, which probably seems like a pedantic distinction but hey — that is what online discussions of video games specialize in.

If you didn’t know about SMB2, this would just look wacky.

Just as Peach inherited all her traits from Doki Doki Panic’s pink cutie Lina, Toad inherited his ability to run fast, lift heavy things, and jump like a sack of garbage from Doki Doki Panic’s Papa, but Toad only functions this way in certain games, like 3D World and arguably Wario’s Woods. You might guess that Luigi’s standard attributes originated with Doki Doki Panic’s Mama, but I don’t think that’s the case: He was already jumping higher than Mario while exhibiting worse traction in The Lost Levels. Luigi’s scuttling, bicycle kick-style jump as seen in Super Mario 64 DS or Super Mario Galaxy 2, however, does originate in SMB2, and that’s unique to him; Mama doesn’t do that — or at least she doesn’t do it in an obvious way beneath her ankle-length dress.

Lookit them legs go!

Because Super Princess Peach is to some extent a follow-up or homage to SMB2, you could also argue that its mechanic of picking up and throwing enemies using Peach’s talking parasol is an evolution of the SMB2 style of play, but I think that it hasn’t been officially, fully revisited until the SMB2 Mushroom item was added to Super Mario Maker 2, allowing Mario to look and play like he did in this game, hopping onto the backs of monsters when jumping onto them would normally result in them being stomped.

Finally, the last major gameplay innovation added to SMB2 would be the creation of Subspace, the sort of photo negative version of the world that Mario can enter to gather coins, find a power-up mushroom or use a warp. Although it’s namechecked directly in Scott Pilgrim, I don’t think this version of a subspace has ever made its way back into another game — and the Super Smash Bros. Brawl story mode, the Subspace Emissary, doesn’t seem like a direct reference despite the fact that the Smash Bros. games basically exist only to reference video game history. The concept of a subspace, after all, is not owned solely by SMB2.

However, it should also be noted that Donkey Kong Country Returns, the game to which Tropical Freeze was a sequel, was also produced by Kensuke Tanabe, and I’m guessing it’s his involvement that resulted in plans to have areas levels rendered in a style distinctly reminiscent of SMB2’s Subspace, though this did not come to pass in the final product.

Even though Doki Doki Panic was not created with the idea of it being or becoming a Mario game, the original version featured both the POW Blocks (which originated in Mario Bros.) and Super Stars (or Starmen, or whatever you want to call them, which originated in Super Mario Bros.). Both these items function like they do in the Mario series, although tagging the star in Doki Doki Panic does not play the SMB invincibility theme. Some people take this inclusion as evidence that Nintendo always wanted to make Doki Doki Panic Mario canon, but I would credit this to the idea of Nintendo being liberal during its early days, in the way Zelda-style rupees appear in Clu Clu Land or the third dungeon boss in Legend of Zelda is supposed to be a supersized Piranha Plant. (In 2011, Tanabe gave an interview where he discussed how much of an influence Mario-style gameplay had on the game that would eventually become Doki Doki Panic.)

Finally, I don’t think any subsequent Mario game ever implemented digging downwards through sand as a gameplay element. Not even Super Mario 3D World attempted that. Maybe that’s for the best?

Music and Graphics

This is a short section to just point out that callbacks to the look, feel and sound of SMB2 seem rarer than those of Super Mario Bros. 3, Super Mario World or Super Mario 64, although the music has begun to fare better in recent years. And with good reason — the game’s soundtrack is all classic-era Koji Kondo, and it’s as good as what Kondo made for any other tentpole Mario game. Not including Smash Bros. games where all music in any game ever is fair game to be remade, here are all the instances of the SMB2 music being reworked into later Mario games.

The first example I can find comes from 2005’s Dance Dance Revolution: Mario Mix, which by virtue of being a nostalgia-mining jukebox-style game does work somewhat like a Smash Bros, but it is technically the first time the series reached back to SMB2.

The next example is Mario Hoops 3 on 3, of all games, which was released a full eighteen years after SMB2; the music that plays when Wart is conquered is repurposed as a victory theme.

The Coaster Hills area in Mario vs. Donkey Kong: Mini-Land Mayhem! features a remake of the overworld theme, plus a few more nods.

The title theme to Paper Mario: Sticker Star seems like it might be a reworking of the SMB2 ending theme.

The slot machine theme from Super Mario 3D World is a remake of SMB2’s character select theme. Even though 3D World is basically one giant lovefest for SMB2, this is the only musical callback, unless I’ve missed something.

The theme of the Spinning-Door Game in Paper Mario: Color Splash is another reworking of the SMB2 overworld theme.

And most recently (as of the original posting of this) the Scamper Shores theme from Bowser’s Fury features a callback to the SMB2 overworld theme around the one-minute mark.

And finally, as detailed in the below video, the introduction of the SMB2 Mushroom to Super Mario Maker 2 meant the revival of not only the game’s overworld theme but also its underground, boss and ending themes, though essentially unchanged from their original versions.

Super Mario Bros. 2 also has a distinctive look, as does every major Mario game, but I feel like it rarely gets nods in subsequent games, whereas, say, raccoon tails have a prominent place in the series today. I suppose you count the use of its trademark red doors in Super Mario Maker or maybe even Super Mario Odyssey as a callback, but the one instance I can point to where I can say, “Yes, this is an intentional visual callback,” is the Super Mario Kart 7 stage Shy Guy Bazaar, which features magic carpets and a pronounced pseudo-Arabian look that I think must be a nod to SMB2, whose own Arabian vibe is a holdover to the fact that Doki Doki Panic starred an family that was… if not Arab then at least vaguely Middle Eastern in the way that many game elements inspired by real-life places or ethnicities tend to color with broad strokes.

The stage even features clay jars that seem to represent the ones that served like pipes in the original Super Mario Bros.

This below video points out that the carpets you drive over in the game incorporate the original SMB2 pixel art for several bad guys who don’t otherwise appear in many other Mario games: Cobrat, Panser, and Phanto.

It’s about as loving and as subtle a celebration of SMB2 as I’ve seen in a later game. This whole stage exists as tribute to the game that gave us the Shy Guy. It’s rather thoughtfully done.

Characters

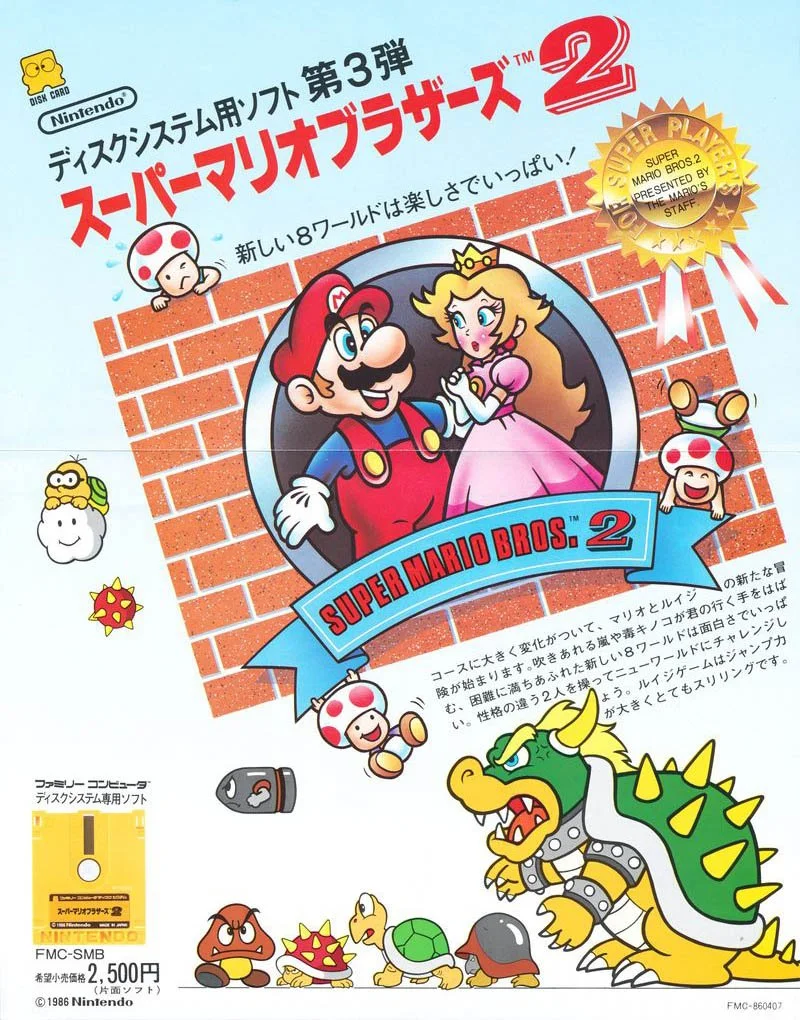

For non-Japanese gamers, the Super Mario Bros. 2 instruction booklet offered us our first glimpse of a version of Princess Peach (then Princess Toadstool) that didn’t look like a blocky mess or a little kid wearing jammies. No drawing of her appears in the original manuals for either the Japanese version or English version of the game. Only in the instruction manual and some versions of the box art for The Lost Levels does Peach finally look much the way she does now — taller than Mario, Farrah Fawcett flip, clunky brooch and all that, though in the below version she retains these odd red spots on her cheeks that also appear in the Japanese SMB cover art. I think they’re supposed to represent rosy cheeks, though they’re drawn in a strange way that kind of makes them look like acne. Either way, I’m glad Nintendo dropped this from her official design.

(In April, manga artist Gaku Miyao posted to Twitter showing off some merchandise featuring a version of Peach that Nintendo ultimately did not use. He also posted a version of what a modern version of that design might look like today.)

Japanese box art for the original Super Mario Bros., featuring a proto-Peach who looks like she’s wearing jammies.

Flyer for the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2 (The Lost Levels), showing Peach looking more like her current incarnation.

The Lost Levels was released in Japan as Super Mario Bros. 2 on June 3, 1986. The anime Super Mario Bros.: The Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach! was released the following month — July 20, 1986 — and given lead times needed to make even an hour-long cartoon, it’s possible that this anime was in production before The Lost Levels was, the original Super Mario Bros. having been released in Japan on September 13, 1985, just nine months before the sequel. What’s interesting about this is that in the anime both Mario and Luigi look somewhat off-model compared to how Nintendo would be depicting them shortly thereafter, whereas Peach looks strikingly on-model. To this day, I wonder if the version of Peach we got in The Lost Levels and, later, the western Super Mario Bros. 2, was influenced by the version drawn for the anime or if the anime version was drawn from Nintendo’s ideas of how they were planning to make her over.

Left to right: a weirdly yellow Luigi, Mario, a very on-model Peach and the foppish Prince Haru, who tragically never crossed over into the games.

Super Mario Bros. 2 is also the game that introduced players to Toad, who is identified in the instruction manual as being one of the princess’s Mushroom Retainers, the Mushroom Kingdom servants Mario rescues at the end of worlds one through seven in the original Super Mario Bros. and who invariably inform Mario that the princess is in another castle.

It always struck me as weird that Nintendo decided to saddle the princess with the clunky name Toadstool and then also assign her little mushroom friend such a similar name; there are more mushroom puns to be made, after all. Toad’s Japanese name also has a mushroom connection — it would seem to be derive from キノコ — kinoko, “mushroom” — but allegedly it’s also a play on Pinocchio, which I suppose makes sense if you think that Pinocchio is a wooden boy brought to life and Toad exists somewhere between a human and a mushroom. That always seemed like a stretch to me, but it gets cited often online as if it’s an obvious connection. I’ve never seen an official Nintendo source confirm that this is the origin of the Japanese name.

The discussion of Toad as a unique character is… complex, to say the least, and I might revisit it in its own post at a later date, but here goes my best effort at sorting it all out.

The SMB and SMB2 instruction manuals, before Nintendo retired the term “Mushroom Retainer.”

What’s interesting about Toad, as he’d be referred to all subsequent English translations, is that it’s debatable how often he is *the* Toad, the one who is playable in SMB2 and who is especially good friends with Mario and company, or just *a* Toad, as the subjects of the Mushroom Kingdom are just generically known as Toads, much in the way there is Yoshi and the Yoshis, Birdo and the Birdos, Kamek and all the generic Magikoopas (カメック, Kamekku) that Bowser keeps on staff. It’s not clear if any of the Toads appearing in shops and castles in Super Mario Bros. 3, for example, are *our* singular Toad or just some rando other Toads.

Unless I misunderstand, this is a distinction that largely does not exist in Japan, where Toad is キノピオ, or Kinopio, who is both one and all of them. I wonder if a reason this distinction wasn’t made in Japan is cultural or simply because they didn’t get our version of Super Mario Bros. 2 early on and therefore didn’t need to force the distinction of *the* Toad versus *a* Toad. This is also not a problem that fans in any country have with Toadette, Toadsworth or Captain Toad — again, unless I’m mistaken. Arguably, if you’re looking at the next time the singular Toad appears in a game, it could be Super Mario Kart (where he is playable), Super Mario RPG (where one Toad uniquely spots the blue vest and red-spotted mushroom cap) or Wario’s Woods (where he’s the hero). To confuse matters further, the Blue Toad appearing as a playable character in the New Super Mario Bros. Wii games is treated as a separate character from *the* Toad, although in Super Mario 3D World that is *the* Toad, just colored blue to reflect his appearance in Super Mario Bros. 2.

But it should also be noted that Japan makes distinctions with Toad that we don’t make at least in English-speaking territories. In addition to Kinopio, there is also キノコ族, or Kinoko-zoku — literally “mushroom tribe” but also sometimes translated as “mushroom family.” Japan also has a distinct, separate Toad that we didn’t really get in non-Japanese-speaking areas: Kinopio-kun, the green-capped Toad who, the spokesperson for Nintendo’s LINE account. Nintendo retired the character in 2021 without giving him the presence on other social media platforms that he had on LINE, so he amounts to a version of Toad that exists there but doesn’t really in most other territories.

Kinopio-kun in a promo for Mario Kart Tour, where he is not actually a playable character.

Kinopio-Kun in a promo for the 35th anniversary of Super Mario Bros., replacing regular Toad in the art, even though he is not actually a playable character.

Kinopio-kun, in a promo for Fire Emblem Heroes, which I have not played but I am fairly certain he is not in this game either.

Finally, there’s Subcon. No, not the setting of the game — which has never reappeared in a Mario game since, and which, while we’re on it, is rather uncreatively named, given that the “It was all a dream!” ending is supposed to be a surprise. I refer to the inhabitants of Subcon, which are also called Subcon — again, uncreatively so. In both Doki Doki Panic and SMB2, there are Shy Guy-looking, fairy-like beings that Wart has stuffed in a jar, and once they’re freed, they celebrate Wart’s defeat and dispose of his corpse. Considering they’ve been a part of Mario mythos since nearly the beginning, we know next to nothing about them, though the similarly fairy-like inhabitants of Sprixie Kingdom in Super Mario 3D World sure seem like a callback to the Subcon, though I’ve never seen any official confirmation of that. (In Japan, the Sprixies are ようせい, or yōsei, “fairy.”)

Left to right: SMB2, BS Super Mario USA, Super Mario 3D World.

In Doki Doki Panic, the Subcon are known as ムウ or Mū, which also happens to be the title of the Osamu Tezuka manga whose title is stylized as MW and which features subject matter much more lurid than what you’d encounter in a Mario game. The manga uses “MW” to mean a lot of things, some literal and some figurative, but the interpretation that’s most relevant to the Mū fairies in this video game is the fact that mū when represented by the kanji 無有, can mean both “both existing and not existing” and “nonexistent.”

This would work nicely with the whole “it was all a dream, it didn’t really happen” ending, but technically speaking, that ending only exists in SMB2 and Super Mario USA. In Doki Doki Panic, the framing device is not a dream but a story, with the hero, Imajin, and his family members being pulled into children’s storybook. Everything they encounter there is both not real, because it’s a product of this fake fantasy environment, but also nonetheless real, because it’s there in front of them. Whereas in the translated Super Mario USA, the setting is called サブコン (Sabukon, obviously “Subcon”), in Doki Doki Panic the setting is 夢宇界 (Mū Kai, “Dream World”), even if the game doesn’t end with anyone waking up in bed and realizing the game never actually happened.

As I was talking to someone about these Japanese names, it was pointed out to me that there is a dream-based Sailor Moon villain named ムーリド or Mūrido. Reversed, that name is ドリーム or doriimu, “dream,” and this is something I will be exploring in an upcoming post about a similarly named Chrono Trigger character.

And with that, with the least memorable characters in the entire game, that’s it for this first post. In the second post, I’ll be detailing the Super Mario Bros. 2 bad guys and how they’ve fared since they made their debut.

EDIT: The day after this website went live, Jeremy Parish’s NES Works series did a video examining the legacy of Super Mario Bros. 2 and exploring some aspects I did not touch on here. Would recommend!