A Speculative Origin for Final Fantasy’s Tonberry

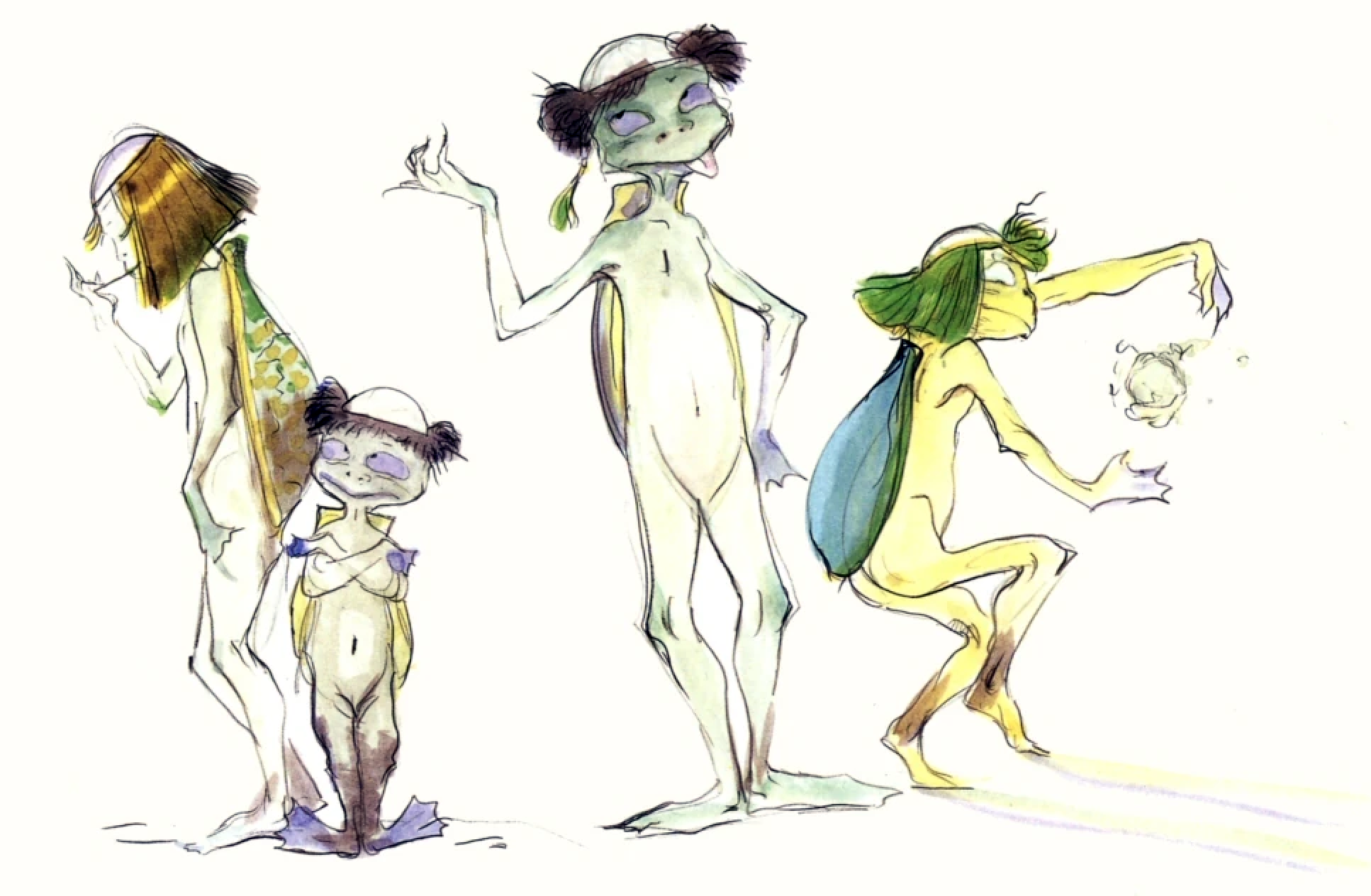

Because so many Final Fantasy monsters come from mythology, folklore or pop culture, it stands out when one doesn’t readily line up with something from the real world. One that has perplexed me for years is the Tonberry, which debuted in Final Fantasy V and which looks more or less like a green salamander wearing a robe and holding a lantern in one hand, a kitchen knife in the other.

Left: The pixelly goodness of the Final Fantasy V version. Right: The smoothed-out version from Final Fantasy VII Remake. I want to kiss his shiny lil head so badly.

Despite looking cute, they’re quite vicious, and their knife attacks can often instantly kill party members. Other special techniques imply a personal vendetta of sorts; the Tonberry frequently uses an attack that damages someone in proportion to how many enemies they have killed, for example, and in Final Fantasy VI another is based on how many steps the player character has taken in the game.

But neither of these aspects accounts for the name, which doesn’t correspond to any one thing in the English-speaking world that I know of and whose Japanese equivalent, トンベリ or Tonberi, apparently so confounded localizers that the monster was renamed Pug and then Dingleberry in the first two games released for English-speaking audiences. It’s been officially the Tonberry from Final Fantasy VII onward, however, and every time I’ve encountered these guys in any subsequent games, I’ve wondered how they got that name, to the point that I included it on this website’s wanted list of video game mysteries. Site analytics show me I’m not the only person wondering about the etymology of the Tonberry’s name, and today I can present you with some well-researched theories — not from me but from reader Lucian Gallacane, whom you may remember as the creator of the video explaining connections between Cammy from Street Fighter and other brainwashed blondes in fighting games. This was also posted on the wanted list, and I gave Lucian’s video its own post when he sent it in.

For this one, I’m not sure we have arrived at a definitive explanation for how the Tonberry got its name, but the research was solid enough — and interesting enough — that I felt like it was worth laying out the various overlapping theories. And because the internet can still sometimes be a fun, collaborative place, perhaps someone reading this post will come up with a way to solve this once and for all.

First of all, the name may result from a connection to Glastonbury, the English town known for various connections to the legends of King Arthur. Most notably, both Arthur and Guinevere were purportedly buried at Glastonbury Abbey, which was allegedly founded by Joseph of Arimathea. I should point out that both these claims are disputed today and have been for a very long time, in addition to a third one about a hill overlooking the town hiding the long-lost Holy Grail. (That hill, Glastonbury Tor, is conjectured to actually be the Isle of Avalon, even if it’s technically a peninsula.) It’s perhaps notable that the Japanese Wikipedia page for Glastonbury is almost exclusively about its legendary associations, whereas the English equivalent gives the kind of comprehensive overview you’d find for any municipality. Today, the name of this town is rendered in Japanese usually as グラストンベリー (Gurasutonberi), but you can also find it as グラストンベリ, as in the title of this Japanese book, and those last four characters are identical to the Japanese name for the Tonberry, トンベリ. And that might seem odd, but I think a plausible connection could stem from the prominence of the monastery in the history of Glastonbury and the fact that the Tonberry looks like it could be wearing a monk’s robe.

There’s something of a precedent for monstrous monks, it turns out. I referred to the Tonberry as looking like a salamander, and it does, but some renderings of it give it a fish’s tail.

The version of the Tonberry from Final Fantasy XII: Revenant Wings has a fishtail and somehow looks even cuter.

That tail might connect it to the seamonk, a fantastical sea creature described as a fish that looks like a monk. Also called monkfish — and not to be confused with the fish in the genus Lophius, which are also called monkfish — this creature was allegedly captured in the waters between Denmark and Sweden in 1546, and it’s not clear by the telling of the story whether it’s supposed to be a variety of fish heretofore unknown to these seafaring people or an actual mer-person. I guess it depends on who is recounting the story, and some weighing in on the subject suggest it could just be a squid, although you’d think people familiar with the ocean would know a squid when they see one.

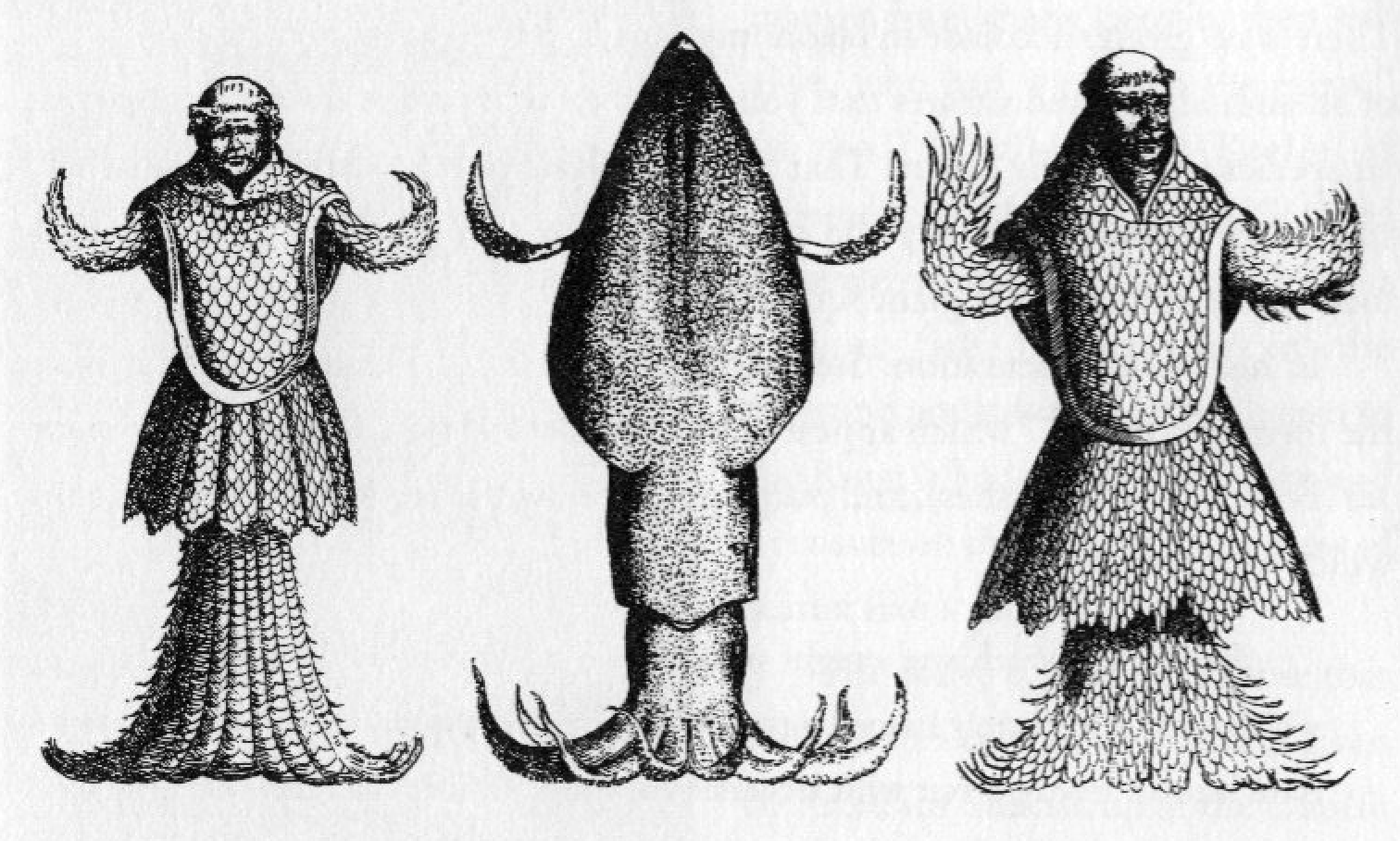

Illustration comparing alleged seamonk to a giant squid by Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup, via Wikipedia. Left: Steenstrup’s take on the alleged seamonk as reported French professor Guillaume Rondelet. Center: An example of the Loligo genus of squid. Right: Steenstrup’s take on the seamonk as reported by French naturalist Pierre Belon.

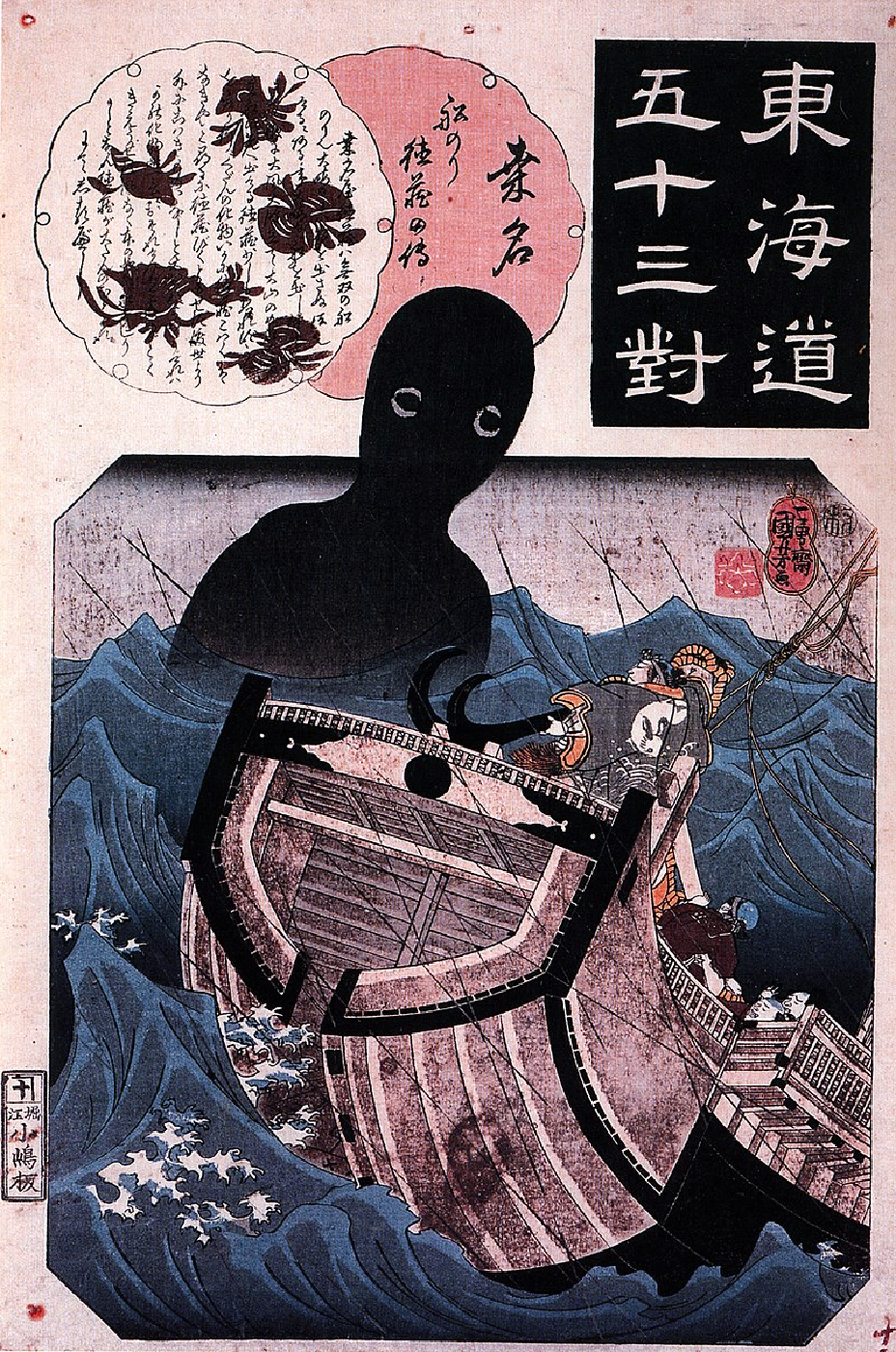

In his email to me, Lucian also pointed out the similarity of this creature to the Umibōzu (海坊主), a Japanese yokai whose name can literally mean “sea priest,” 海 meaning “sea” and 坊主 referring to a Buddhist priest or a person with a shaved head or close-cropped hair, depending on the usage. The Umibōzu is associated with calm waters suddenly turning violent and the shipwrecks that can result, and I’m not sure if this makes the seamonk explanation for the Tonberry’s name any more or less believable, aside from maybe providing a precedent in the mind of a Japanese person for monk + dangerous aquatic monster.

Illustration of the Umibōzu from Fifty-Three Parallels for the Tōkaidō, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, via Wikipedia.

Another connection may lie in a different monk: Dom Pérignon, a seventeenth-century Benedictine friar erroneously credited with inventing sparkling wine but for whom the fancy champagne is named nonetheless. The name, both of the monk and the champagne variety, is properly written out in katakana as ドン・ペリニヨン (literally Don Periniyon), but you see it shortened as ドンペリ or donperi, which is very close to the Japanese rendering of the Tonberry’s name, トンベリ. In fact, the disambiguation at the top of the Japanese Wikipedia page for the champagne actually points to the page for the Final Fantasy monster in case someone mistypes what they’re looking for. Not only that, there’s actually a character in Trials of Mana who is named Donperi, and the fact that it could be referenced in one Square franchise makes me think it could just as easily be referenced in another.

It’s not even the only instance of alcohol being linked with a Final Fantasy creature, and, in fact, researching the other one leads us down some odd connections to the kappa of Japanese folklore. In Final Fantasy VI, there’s a green cherry item that cures the status effect that causes a character to be turned into a strange, green creature known as an imp in the English localization but as a kappa in the original Japanese. In Japan, the green cherry is actually the イエローチェリー (Ierō Cherī), the significance being that the name of the Japanese sake brand Kizakura literally means “yellow cherry.” Not coincidentally, the brand’s logo is a kappa.

What’s especially interesting about this is that the green cherry shows up in a different context in the back half of the game, during the battle with Umaro, the yeti you must defeat before he joins the party. In battle, Umaro uses the green cherry item and it inexplicably gives him a status boost. Based on this information, I think the implication is that he’s getting drunk? Or at least taking a swig of booze to help him win the fight?

That’s not the only connection between the Tonberry and the kappa, Lucian pointed out. In general, it’s a disadvantage for a character to be transformed into one of these creatures, but if properly outfitted, you can turn them into a lean, green powerhouse. You just have to collect all four pieces of equipment — the Imp Halberd, Imp Armor, Tortoise Shield, Titanium Helm in the original English localization and the Impartisan, Reed Cloak, Tortoise Shield and Saucer in the later, amended localization.

One of the ways you can collect these items is to fight a Tonberry and use the Ragnarok summon, which effectively kills enemies by transforming them into items. There’s not necessarily a reason why any given enemy is associated with any given stealable item, and in this case there doesn’t seem to be one aside from both the Tonberry and the imp/kappa green creatures with links to booze and real-world cryptids, but the connections actually don’t end there.

The Japanese name for the Impartisan is the Spear of Sagojō (さごじょうのやり or Sagojō no Yari). This name should be familiar, as it came up in my piece on how the kappa influenced the Super Mario series’ Koopa Troopa. He is the character in sixteenth-century novel Journey to the West whose name in the original Chinese version is Sha Wujing. In all versions of the story, he’s a bald-headed monster residing in a river of flowing sand who is recruited to join the party of the story’s hero, although in the Japanese version of the story, his monster form is specifically that of a kappa. Either way, he converts to Buddhism and dons a monk’s robe, and two of the names he goes by in English translations, Friar Sand and Sand Monk, reflect this. His other names, however, include Sand Fairy, Sand Orc, Sand Ogre, Sand Troll, Sand Oni, Sand Demon and Sand Monster, so he is, like the Tonberry, an odd combo of the monastic and the monstrous.

Like I said at the beginning of this post, I don’t think any of this adds up to a definitive origin for this monster, but I thought the research so far was notable enough on its own. If I had to take a wild stab at drawing all of this together, I’d say that the Tonberry is a monk-like creature, possibly inspired by the seamonk, with the connection to booze stemming from the fact that many varieties of alcohol are associated with religious orders, the liqueur Chartreuse being perhaps the most famous example. Furthermore, alcohol is not infrequently aged and stored in caves or underground, because these were one of the few reliably temperature-controlled spaces before the Industrial Age, and the Tonberry sort of looks like a monk patrolling for poachers. He’s carrying a lantern because caves are dark, and he fights with a kitchen knife because that’s what he had handy. He’s not a warrior; he’s just defending his turf from randos who aren’t supposed to be there.

That doesn’t encompass everything, I guess, and it doesn’t explain why these little guys hit so consistently hard, but I’m open to anyone else’s interpretation of some or all of what we’ve laid down in this post.

Again, credit goes to Lucian Gallacane, who reached out to me with the majority of what’s in this post. Follow his YouTube channel to see what kind of research he does in the future. And if you have an idea for what I should cover on this website, reach out to me, either in the comments or on the contact page.

Miscellaneous Notes

The one theory that I’m just going to nix altogether is that the Tonberry’s name comes from some combination of the words tomb and bury. It’s brought up on this Japanese site, and for whatever reason my gut feeling is that this is not correct, associations with King Arthur’s final resting place notwithstanding.

For what it’s worth, the Cactuar can also be transformed into the imp/kappa equipment in Final Fantasy VI, and the only thing it has in common with the Tonberry or the kappa is the color green… unless you consider that the Cactuar, like the Tonberry, is a rare enemy in the game and therefore all three of them have a sort of crytpid-like quality. Hmm…

In the Final Fantasy Anthology localization of FFV, released in 1999 for the PlayStation, the Tonberry is given the name Dingleberry. And I honestly don’t know exactly how to interpret that. That term has meant “a stupid person” for the last century or so, and while I’d assume that is the sense of the term being used in this game, there is a grosser definition that I am not discounting because this is, after all, the version of the game that named the hero Butz rather than Bartz, among many, many, many other bad localization choices. I’ve found that many people aren’t familiar with the older definition of the term and assume that all uses of the word refer to the newer definition — there’s a Seinfeld episode where someone refers to “Jerry Jerry Dingleberry,” for example — and that’s just not the case. Weirdly, a dingleberry can also be a type of cranberry, but I assume no one wants to eat it now.