Why Is the Big Bad of Bubble Bobble Named ‘Super Drunk’?

I need to tell you why Bubble Bobble is weird.

No, it’s not because it’s a game about bubble-spitting dragons trapped in a candy-colored labyrinth and forced to turn various monsters into food products, although I have to admit that is weird, now that I think about it.

And no, it’s not because a game about bubble-spitting dragons ended up spinning off into a bunch of different ways, to the point that I’m still not clear what the actual sequel to Bubble Bobble technically is, although I will attempt to sort this out in the miscellaneous notes part at the end of this post.

What I’m actually talking about is more or less confined to the first game, which debuted in arcades in 1986. The original Bubble Bobble has more plot than you might guess, considering it doesn’t really need anything more extensive than “go kill all the monsters before they kill you,” but at the same time the backstory raises a lot of questions about the world in which the game takes place. For one thing, the heroic, bubble-spitting dragons you can control — Bub, the green one, and Bob, the blue one — aren’t actually dragons, but human boys who are named Bubby and Bobby and who were cursed into bubble dragon form by the same big bad who made off with the boys’ girlfriends, Betty and Patty. This villain is waiting for Bub and Bob on the one-hundredth level of the Cave of Monsters, which is an odd name for the candy-colored, food-filled labyrinth I mentioned earlier, but I suppose it’s not any stranger than the villain turning the boys into dragons that spit bubbles, since bubbles are the one thing monsters in the cave are weak against. Anyway, when Bub and Bob finally get to the hundredth floor, they square off against that big bad, whose name is… Super Drunk, which is a very odd name for the final bad guy in any video game.

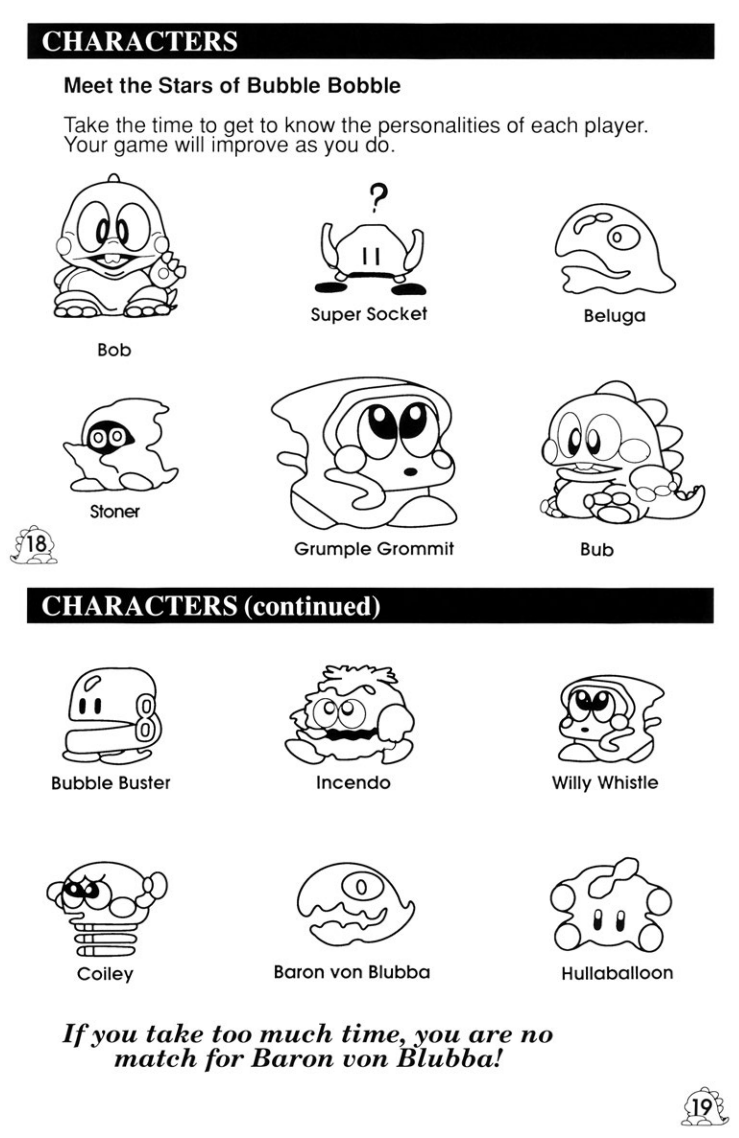

This is what Super Drunk looks like.

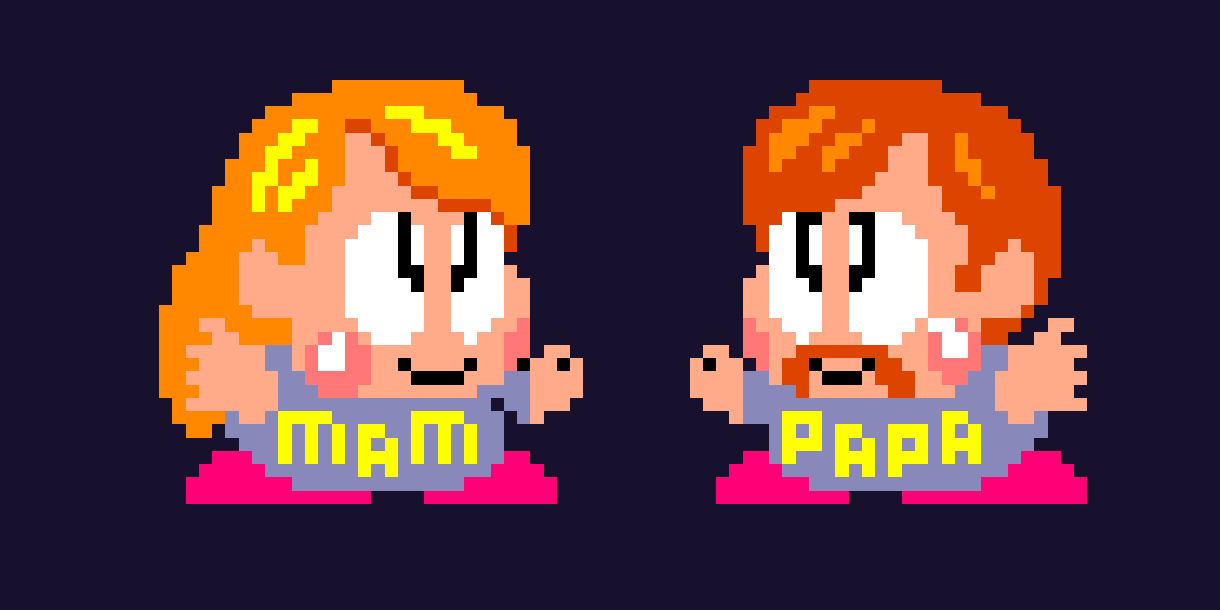

All of this is made even stranger, however, when the boys emerge victorious and it turns out that the villainous Super Drunk is actually their parents, who helpfully wear shirts identifying their relationship to the heroes.

It’s quite the reveal, as previous to this point in the game, we didn’t even know the hero characters even had parents, much less that they’d be lurking in the form of the game’s big bad.

To summarize, two twin boys (both ten years old) who are dating two twin girls (also ten years old) venture out into a magical forest, where they’re accosted by Super Drunk, who kidnaps the girls but also turns the boys into magical dragons whose special bubble powers ultimately bring about his own undoing, at which point it’s revealed to everyone’s surprise that Super Drunk was actually Bub and Bob’s own mother and father, fused together Crystal Gem-style into a single body at some unspecified point in time before the game’s story takes place.

If I explained this basic outline to my therapist as a story I’d written, I think he’d have some really understandable follow-up questions about my relationship to my parents, the role alcohol played in my household growing up and, quite possibly, trauma that I might be sublimating into a fairy tale that uses some archetypal imagery and then also a lot of weird stuff that just does not make much sense. None of this arose from my subconscious, however. It came from Taito designer Fukio “MTJ” Mitsuji, whose psychological underpinnings I don’t feel qualified to comment on. In a 1988 interview with Beep, a Japanese gaming mag, Mitsuji explained that he came up with the idea for Bubble Bobble in an effort to create a video game that appealed to girls. And in a 2005 Taito Legends interview, he said that his plan seemed to have worked, as he’d often see women playing Bubble Bobble with their boyfriends. In no interview could I find Mitsuji or anyone else associated with the game explaining why the heroes’ parents should body-meld into a villain named Super Drunk.

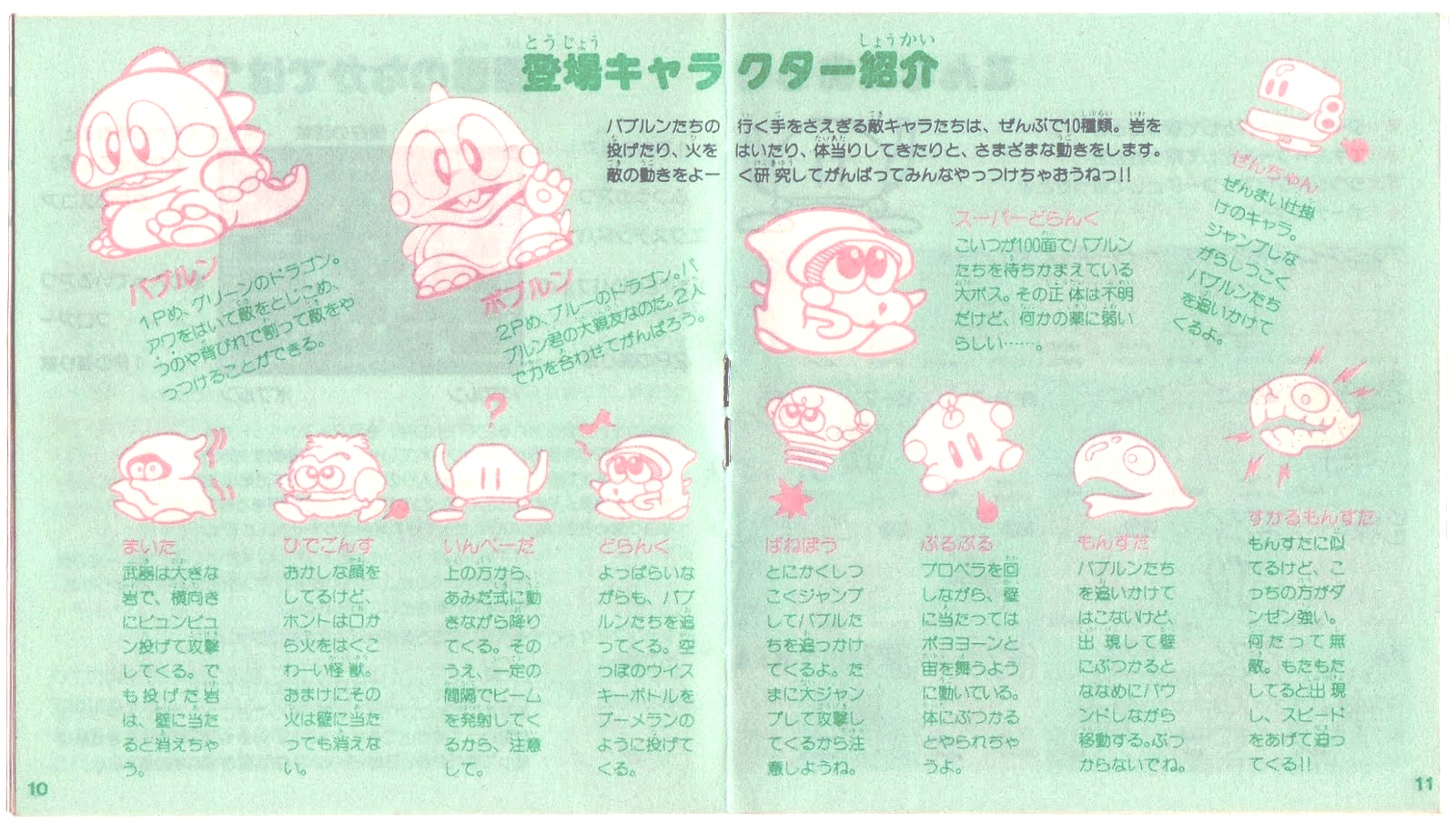

Just because it’s often the case, I assumed this character name had to be a mistranslation. It is not. In Japanese, he’s すーぱーどらんく (Sūpā Doranku), and he’s actually just a supersized version of a regular recurring enemy, Drunk (どらんく). And the generic Drunk is named that for good reason, too, as his method of attacking Bub and Bob is chugging whiskey from a bottle and then hurling the bottle at them.

“But wait a minute,” you may be saying, “if he’s a drunk who throws liquor bottles, why does he dress like a wizard and carry a wizard’s staff?” That’s a good question, I say, because nothing about his appearance suggests anything I’d associate with a chronic alcoholic. Also, it’s only Super Drunk that seems to command magic powers, at least in this first game. Despite dressing the same, the regular, generic drunks cast no magic and just throw empties. That’s confusing, from a world-building standpoint, but just the name alone would seem to violate Nintendo’s policies forbidding objectionable content. This would be the same set of rules I discussed in posts about the Tower of Babylon in Super Mario Bros. 3, a devil character in Wario’s Woods and overall satanic imagery in Ghosts ’n Goblins, but in addition to banning most religious imagery, Nintendo also forbade references to alcohol, hence, for example why Bowser and Peach’s victory screens in Super Mario Kart were censored so they wouldn’t be shown chugging champagne. The timeline for these policies is a little shaky, however. Per this Legend of Localization post, we know that these rules were in full effect by 1994, but as far as I know we don’t have much evidence for how soon before that Nintendo of America began asking for booze references to be stripped out of games before their release on the North American market.

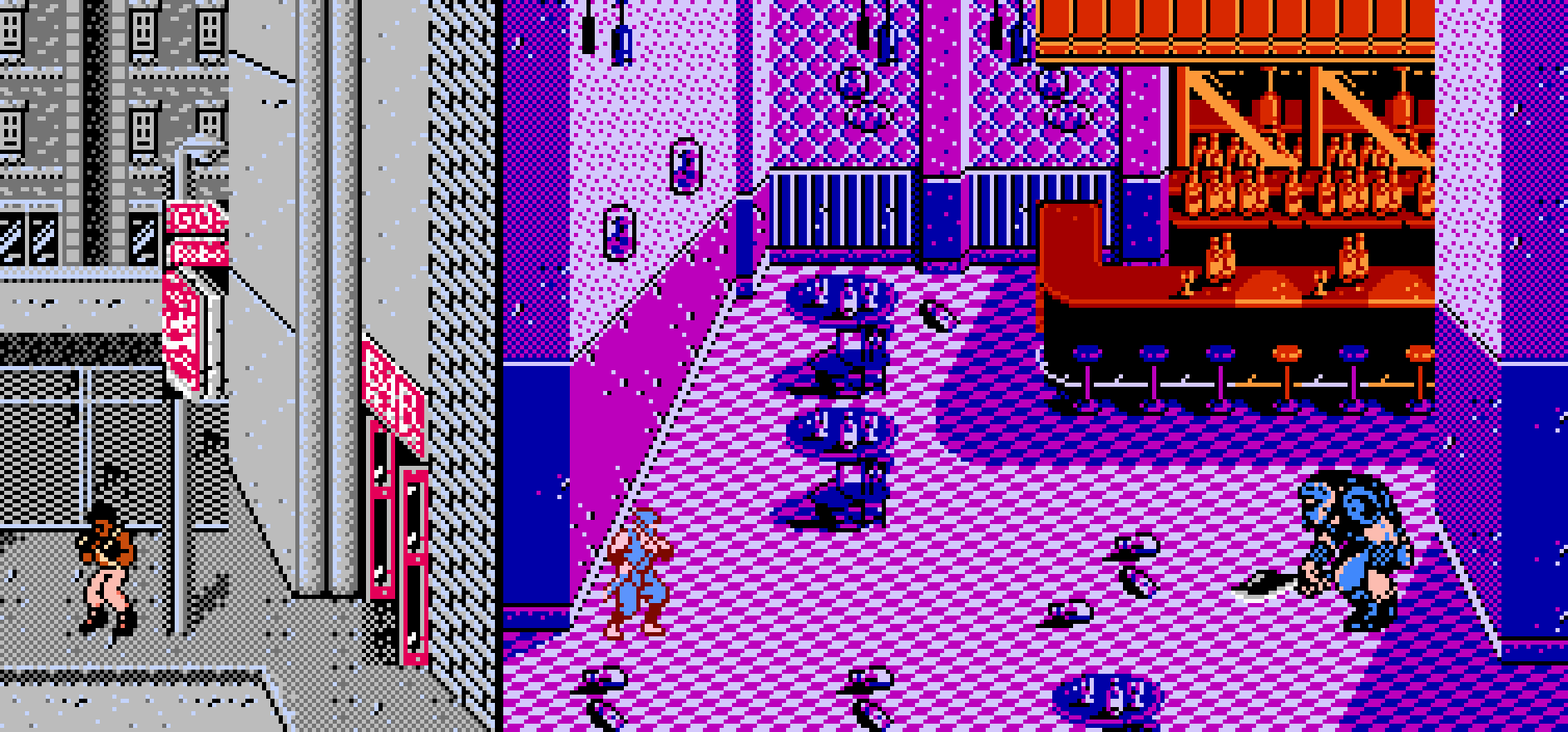

The NES port of Bubble Bubble was released November 1988, and by then alcohol censorship was a bit of a mixed bag. For example, the character that debuted in the 1984 Nintendo arcade game Super Punch-Out!! as Vodka Drunkenski became Soda Popinski for the home console version, but that happened both in the North American release and the original Japanese one, both in 1987. Hitting shelves in March 1989, however, the NES port of Ninja Gaiden has its first boss fight in a building clearly labeled as a bar — and once inside, bottles are visible both on the shelf and on tables. Clearly, no effort was made to disguise the fact that this was an establishment that served alcohol.

The NES port of Mappy-Land also preserves references to alcohol — as well as to religious iconography.

But alcohol reference in the detective noir game Deja Vu, released in North American in December 1990, did have its booze references scrubbed out, including a glass of whiskey transforming into just seltzer, even if the window in the background identifies the location as Joe’s Bar.

While the original Japanese version of the instruction manual for Bubble Bobble clearly identifies both Drunk and Super Drunk with their “correct,” boozy names…

… the English version gives Drunk a wholly new, alcohol-free name, Willy Whistle, which doesn’t mean much of anything. It also saddles Super Drunk with a name so cutesy-poo that it could come out of any third-rate line of western 80s toys: Grumple Grommit. You might think that these new names came about specifically because Taito wanted to avoid anything even remotely PG for this release, but weirdly all of the enemy characters were given new, worse names.

Inexplicably, the name the game assigned to the white-robed monster character, called まいた (Maita) in Japan, was changed to Stoner, seemingly referencing narcotics in a way where no such reference existed before. And this makes me think that whoever was in charge of localizing Bubble Bobble actually either wasn’t concerned at all about illicit substances or was just really bad at removing them. I mean, seriously.

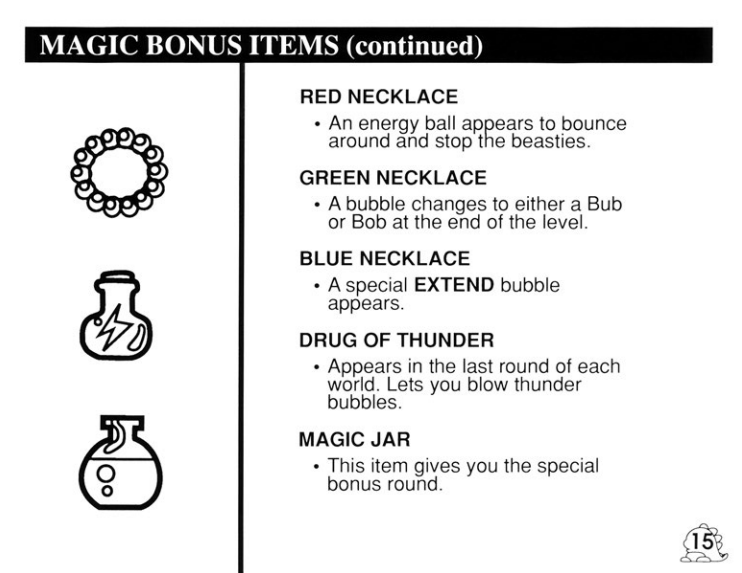

The one thing about this game I haven’t explained yet is that in the final fight against Super Drunk, you will quickly find out that Bub and Bob’s regular bubbles don’t seem to affect him. Instead, they’ll need to snag these potion-looking items in order to give them the power to create thunder bubbles that, when popped, send lightning bolts whizzing across the screen. Only when you’ve shocked Super Drunk enough does he transform first into an extra large bubble dragon and then into the heroes’ parents. Bizarrely, the official name for this item — in both the original Japanese version and the localized English version — is Thunder Drug (ドラッグ・オブ・サンダー or Doraggu obu Sandā). Again, this is a weird name choice.

I should preemptively point out that I do understand that the word drug can refer to more things than just illegal narcotics. I have been to a drug store, after all. But also you have to understand that both I and the video game Bubble Bobble were born during a time when the only real use this word had as far as American children were concerned was referring to a bad thing that Nancy Reagan wanted us to say no to. I don’t know to what extent this double meaning exists with Japanese words referring to pharmaceuticals and narcotics, but at the very least the loanword ドラッグ (doraggu) would seem to carry those connotations abroad. And even if it didn’t, it’s surprising to me that the English language manual for Bubble Bobble would retain that word when potion would have avoided the narcotic associations easily. (Some later games apparently localize it as tonic, which also works.)

I bring up the whole Thunder Drug thing because if you’re looking at Bubble Bobble as a work that is commenting on the dangers of substance abuse — and yes, I realize how inherently ridiculous that sounds — then it kinda sorta tracks up until this point. Making the heroes take a drug in order to defeat the big bad muddles the message, if you’re telling yourself there actually is a message here. But also? Of fucking *course* this reading doesn’t hold up at all, because in all likelihood that message was never intended by anyone who made this cutesy game about bubble-spitting dragons. If that’s the case, however, then you also have to admit that for something that wasn’t meant to offer any kind of commentary on substance abuse, then there are a few bits here and there that seem like they almost add up to something but then just fall short.

Like I said at the beginning of this post, Bubble Bobble is weird, and in the end, the weirdest thing about it is not that it features some hidden anti-substance abuse message but instead that its big bad is named Super Drunk and it makes you take drugs and somehow it’s *not* intended to feature some hidden anti-substance abuse message. A lot of the time, you can’t find definitive answers for how these old video games ended up the way they did — and I’m saying this as someone who spends a lot of his time looking to see what’s there. In the case of Bubble Bobble, I suppose we won’t get answers, as Fukio Mitsuji died in 2008 without sharing his thoughts about any symbolism that ended up in the game, intentionally or otherwise. I have a feeling if it had been brought to his attention, he would have laughed it off as a coincidence, as these were not themes that video game creators were using the medium to explore back in the day.

That said, it’s also worth considering how someone else might find evidence of a thematic throughline in a work that its creator never intended. After all, our creative impulses often spring from the same part of our brain where dreams and other subconscious thoughts exist, and it happens not infrequently that we end up revealing more than we intended when we create something for public consumption. Of course, the fact that I’ve latched onto this theory probably says as much about me than it does Mitsuji, and now I’m wondering what themes I’ve woven into this blog, accidentally telling you the reader about things that I never intended to share.

What a weird thought. I want a drink.

Miscellaneous Notes

I’m going to keep this one vague for the sake of spoilers, but let’s say hypothetically there was a certain up-and-coming horror director who helmed two successful films. And let’s say both of them hinged around characters that were, in their own way, monstrously twisted versions of maternal figures. You’d have to wonder if anyone — his friends, his wife, his therapist, his mother — might have pointed this out to him and an effort to gauge what issues he might be repressing in a way that have surfaced twice in his work. Hypothetically speaking, of course.

Two of the enemy characters appearing in Bubble Bobble actually debuted in Chack’n Pop, a 1984 Taito platformer that is sometimes viewed as a spiritual predecessor: the aforementioned Maita and then also Monsta, the purple, whale-looking guy that’s known in the west variously as Beluga or Blubba. According to the sheets posted at Spriter’s Resource, the Zen-Chan enemy was also supposed to appear in Chack’n Pop but went unused in the final version of the game. Years later, the Bubble Bobble sequel Parasol Stars would debut a new generic baddied based on Chack’n Pop: an evil version named, of course, Ack’n Pop.

Both the Drunk and Maita enemies appearing in this series bear a certain resemblance to the Shy Guys from the Super Mario games. And I guess it could be just because that’s how you draw a weird little guy wearing a robe, but someone did recently ask me if the Shy Guy’s design was inspired by anything in particular in pop culture, and seeing how similar these Bubble Bobble guys look like, I’m inclined to ask. Is there something they’re all based on?

It’s maybe not surprising, but apparently Drunk is both a singular character and also a generic species, much in the way Toad and Yoshi are in the Super Mario games. I could be mistaken, but in the occasion that you can play as a Drunk in one of these games, it seems like it’s usually supposed to be the singular Drunk character and not just any other Drunk, if that makes sense. Weirdly, his name has been changed in more than one western release to Dreg, and I’m not sure why. It could be to differentiate this singular character from all the other Drunks, I suppose, but if it’s meant to limit the alcohol association, the name Dreg misses the mark because as a generic word, dreg is often used in reference to sediment in wine, to the point that the 1980s version of Strawberry Shortcake featured a wine-themed villainess, Sour Grapes, who had a pet snake named Dregs for the same reason. But in other localized Bubble Bobble games, Drunk keeps his original name, resulting in fun locations such as Drunk’s Castle.

There’s also a female version of Drunk, Dranko (どらんこ or Doranko), who is visually differentiated from her male counterpart by being extra cute. She even has a supersized version, Super Dranko.

So what’s the sequel to Bubble Bobble? Well, at first glance the most obvious contender would be Bubble Bobble Part 2, released in 1993 for both the Famicom and NES. The game focuses on descendants of Bob and Bob, Cubby and Rubby, though that’s made a lot less clear in the western release. But despite what the title implies, the game’s plot seems to take place after Rainbow Islands, the 1987 game that followed the adventures of Bubby and Bobby, the human forms of the heroic bubble dragons from the original game, who now fight monsters using some rando rainbow magic. To complicate matters considerably, the full title of this game is Rainbow Islands: The Story of Bubble Bobble 2, but the destruction of the big bad in this game, Super Skel-Monster, is a plot point in Bubble Bobble Part 2, so clearly there’s an intended continuity here. In 1991, Rainbow Islands got its own sequel, Parasol Stars (again starring the human versions of the hero characters), but in 1994, Taito released a new arcade sequel, Bubble Symphony, which is also known as Bubble Bobble II. This game featured the return of the bubble dragon forms of the heroes plus those of Betty and Patty, whose names are apparently Peb and Pab. (No, I don’t understand why they’d give themselves new names for when they become bubble dragons.) In 1996, Taito released another arcade sequel, Bubble Memories, the full title of which is apparently Bubble Memories: The Story of Bubble Bobble III, so I guess at that point Taito had officially moved onto a new number, but I don’t know how this retroactively affects the chronology of the other games that were also versions of Bubble Bobble 2. The series got two additional entries — Bubble Bobble Revolution in 2005 and Bubble Bobble Plus in 2009 — but I’m guessing neither of those count as official, canonical sequels meriting a number, because in 2019 Taito released Bubble Bobble 4 Friends, the title of which makes me think it’s meant to be considered the fourth game in the series.

In reading through a lot of Bubble Bobble lore to compile the previous paragraph, I found out that in at least one version of Bubble Bobble, Final Bubble Bobble, Super Drunk has two sons. I don’t know how this affects the fact that Super Drunk is also Bub and Bob’s parents. Are Bub and Bob just Super Drunk’s sons? What a weird continuity.

Finally, I realize anyone with a mouth that makes saliva can conceivably use it to make bubbles, but is there any reason the Bubble Bobble dragons and Wart in Super Mario Bros. 2 both spit bubbles as weapons? Like, reptiles and amphibians can’t do this in real life, but is there a pop culture reason why lizards or frogs do these in these two instances? Can you think of another example? Is it a reference to something I’m just missing?