How Popeye Changed Video Games

Popeye lives — just not so much in the medium that made him famous.

Earlier this summer, I was listening to a dauntingly thorough feat of podcasting about Who Framed Roger Rabbit. The episode clocked in at nearly seven hours, because a lot of animation history is crammed into the 1988 film. One of the things the episode pointed out is that even though Who Framed Roger Rabbit features most of the major players of classic animation, it does not feature Popeye, a fact that had never previously occurred to me

Then again, there might be good reason why I never thought about it before: Popeye’s star was dimming, even back when Who Framed Roger Rabbit was released. I knew who Popeye was because I’d seen some of his classic shorts, and also because Dave Coulier did his Popeye impression on Full House like it was going out of style. (It was.)

The 1980s were not as kind to Popeye as they were to other old-school cartoons. Hanna-Barbera’s Popeye & Son ran for just 26 episodes, all of which were burned off two at a time on CBS every Saturday between September and December of 1987. This reboot was a result of the same “quick, remake it for ’80s kids!” impulse that also produced The Flintstone Kids and Pink Panther and Sons. I’m not sure the Popeye version was all that memorable, aside from giving Olive Oyl an excuse to wear aerobics gear.

Unless I’m mistaken, Popeye and Son was the last series to realize Popeye in new animation, aside from a 2004 CGI Christmas special. Based on an animatic leaked in July 2022, there may yet be an animated Popeye movie directed by Samurai Jack creator Genndy Tartakovsky. For the most part, however, Popeye has fallen out of the public eye. And that’s too bad, considering how beloved the character once was.

But even if he’s no longer a cartoon star like he once was, Popeye lives on in video game form in ways that his creators would have and could have never envisioned — and in ways video game fans may not even realize. These legacies testify to the tremendous sway the character once held over pop culture the world over. In this post, I’m going to list off the ways Popeye has endured, if sometimes invisibly.

Popeye is (indirectly) responsible for Mario existing

This is probably his most well-known video game legacy. It’s also the contrinbution most people reading this probably thought of when I suggested a connection between Popeye and gaming. The short version of this story is this: Nintendo wanted to make a Popeye video game, but after abandoning that plan, the company just invented new characters. As a result, we got Mario, Donkey Kong and Pauline.

This TL;DR version of the story leaves out a few details, however. For example, in a 2009 edition of Iwata Asks heralding the release of New Super Mario Bros. Wii, Shigeru Miyamoto says he does not know why Nintendo was denied permission to make a Popeye game, especially because the company was already making Popeye merchandise in the form of playing cards, possibly as far back as the 1960s.

Miyamoto: Having rigorously analyzed what exactly made people want to play one more time, I sketched out ideas for five games. At this point, Nintendo was the licensee for Popeye.

Iwata: Yes, the company was releasing Popeye playing cards and Popeye Game & Watch titles.

Miyamoto: That’s why at first I asked if I could make a game using Popeye. The basic concept of Popeye is that there is the hero and his rival who he manages to turn the tables on with the aid of spinach.

Iwata: When you put it like that, it's the same as Pac-Man, isn’t it? (laughs)

Miyamoto: Yes, it’s identical to Pac-Man! (laughs) So I sketched out a few ideas for games using Popeye. At that point, Yokoi-san was good enough to bring these ideas to the president’s attention and in the end one of the ideas received official approval. Yokoi-san thought that designers would become necessary members of development teams in order to make games in the future. And that’s how Donkey Kong came about.

Iwata: But originally it was going to be a Popeye game.

Miyamoto: That’s right. But while I can’t recall exactly why it was, we were unable to use Popeye in that title. It really felt like the ladder had been pulled out from under us, so to speak.

Iwata: So even though you were making a game about climbing ladders, you had the ladder pulled out from beneath you before you even got started! (laughs)

Miyamoto: Great gag! You deserve a standing ovation for that one! (laughs) Anyway, at the time we were at a loss as to how to proceed. Then we thought: “Why not come up with our own original character?”

Iwata: So basically Donkey Kong and Mario came about once the ladder had been pulled out from beneath you.

Miyamoto: Exactly.

Iwata: Miyamoto-san, you really do lead a charmed life!

It is interesting to me that Nintendo’s first attempt at licensing another company’s copyrighted character was Popeye and not, say, Mickey Mouse, seeing as how Nintendo had a deal with Disney to put its characters on playing cards at least as long as it had a similar deal with King Features, the Hearst-owned syndicate that controls Popeye. As I will discuss in the third section of this post, Popeye enjoyed a great deal of popularity in Japan, so perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that Nintendo would try to get him — a character with a lot of recognition, but who might come somewhat cheaper than Mickey Mouse, let’s say — into a game early on.

What’s curiously absent in any discussion of this early attempt to make a Popeye-themed Nintendo game, however, is the fact that it would have been happening around the same time as the 1980 Robert Altman-directed live-action Popeye film. Starring Robin Williams as Popeye and Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl, the film was critically panned and deemed a flop upon its initial release, though it would eventually earn back its $20 million budget three times over and experience a critical reappraisal as the decades ticked on. (The next week, 9 to 5 opened in theaters and blew Popeye out of the water, raking in more than any 1980 film other than The Empire Strikes Back. It also starred Lily Tomlin, who at one point was meant to play Olive Oyl opposite Dustin Hoffman’s Popeye.)

This movie is… weird. If this is a thing you have not experienced firsthand, watch a bit of the trailer. It’s disquieting seeing the physics of Popeye’s cartoon world translated to real life realized in drab ’70s colors. It plays like a dream, but not a particularly nice one.

Despite my best efforts, I can’t find any definitive statement, from Nintendo or King Features, explaining why the latter refused the former the rights to the Popeye characters. I’m not even sure if the idea to make a Popeye game had anything to do with the movie. It’s possible that the Popeye movie being perceived as unsuccessful could explain why Nintendo staffers don’t bring it up in their recollections — they might just have forgotten that there ever was a live action Popeye, as many people do — but it also might explain why King Features was hesitant about licensing its characters out to other companies.

At the time, Nintendo wouldn’t have been viewed as a top-tier video game company. In fact, the reason Nintendo was scrambling to come up with a new game idea was in part an effort to recoup losses relating to the failure that was Radar Scope, a 1980 arcade shooter that found success in Japan but not the U.S. According to Chris Kohler’s book Power-Up, more than 2,000 of the 3,000 Radar Scope units the company had shipped to the U.S. went unsold, forcing the company to conceive of new software to sell the old hardware. Miyamoto famously came up with the idea for what would become Donkey Kong and would exemplify what we now call the platformer genre. Gunpei Yokoi was appointed to supervise the project, and it’s with him that we get another solid Popeye connection: the 1934 short “A Dream Walking,” which takes place on a construction site.

There is a quote from Yokoi about this short being a direct inspiration, and while it’s often credited to the blog The End of Deep Layer, the blog itself states that the quote comes from the book 軍平横井ゲーム館 (Gunpei Yokoi's House of Games), published in 1997 in Japan and consisting of an interview of Yokoi by journalist Takefumi Makino. Yokoi explains that the short provided the essence of the game, which remained even after they knew they would not get the rights to the Popeye characters.

Pretty early on we had decided that Popeye would go on the bottom of the screen and Bluto would be on the top, thus establishing the framework for the game, but we would later discover that we wouldn’t be able to get the rights to use the characters after all. With no other options, we decided to keep the content of the game as it was and just change the characters. And so it was that those characters became Mario, Donkey Kong, and Princess Peach.

A considerable time later, when a certain movie company contacted me and said that our game was infringing on the copyrights to King Kong, I told them this story too; that we were originally trying to make a Popeye game.

Mr. Miyamoto created the character Mario. He said he was thinking about how he should change Popeye, and decided that since the setting for the game was a construction site that he would make a character wearing a work uniform. He was also the one who gave the character a mustache. At first though, we simply referred to the character as “Ossan” But when we sent the finished character design to Nintendo of America, there was talk that the character greatly resembled an employee working there named Mario, and before long the name stuck.

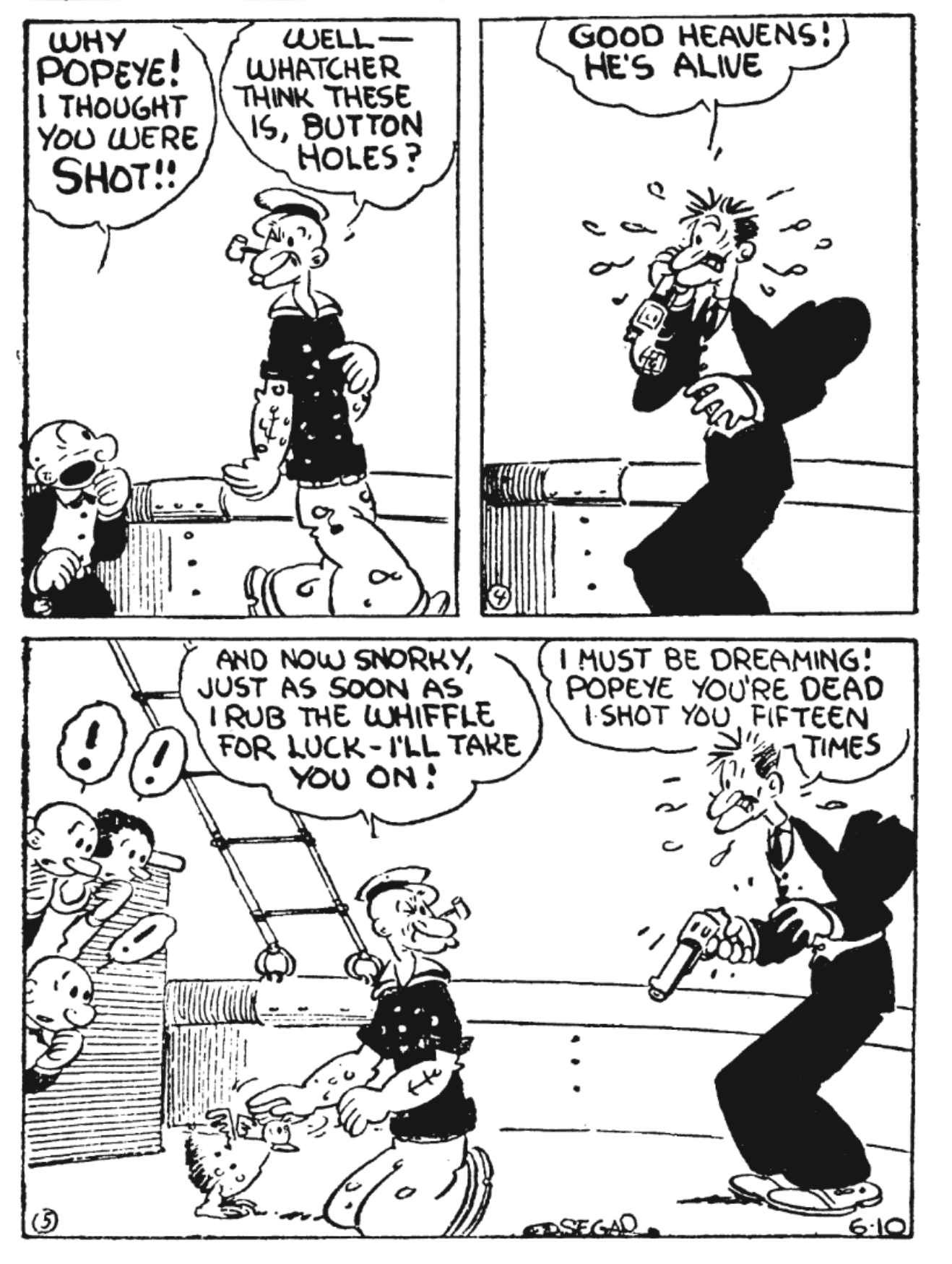

There was an episode in the cartoon show for Popeye in which Olive was sleepwalking and wandered around a construction site. Whenever she was about to lose her footing, miraculously enough another platform would come out of nowhere and support her, and this left quite an impression on me. So we figured by using a construction site as the setting, there would be all kinds of things we could do, and thus chose that as the setting for our Popeye game.

Once we had established that the game would be set at a construction site, Mr. Miyamoto suggested, “Let’s make it a game where there are barrels falling from above, and the player has to dodge them.” At that time, he had a simple gameplay idea which was that whenever a barrel fell the player could get on ladder and avoid it. Once the barrel had passed, the player would get off the ladder and then back on the platform to continue climbing.

Yokoi is misspeaking when he remembers Peach, not Pauline, being the damsel in distress in Donkey Kong. Nonetheless, this is more of a clear “we took the idea from here” admission than we often get in developer interviews, and it’s wild to think about the idea for a cartoon becoming so iconic in another medium nearly fifty years later. Whenever you see those magenta girders popping up in-game today, it’s a callback to Donkey Kong but also to a Popeye short you may never have even seen.

(EDIT: After the posting of this, it was brought to my attention that in a deposition in the 1983 lawsuit between Universal Studios and Nintendo, Yokoi recalls the facts of this differently, saying not that work on the Popeye game ceased because Nintendo failed to secure the rights, but instead that the graphical limitations of the time meant that Nintendo could portray Popeye characters in a way that was satisfactory. Per this version of the story, it’s unclear whether the ultimate decision to cease work on the Popeye game came from Nintendo or King Features. I will be exploring this matter in a future post.)

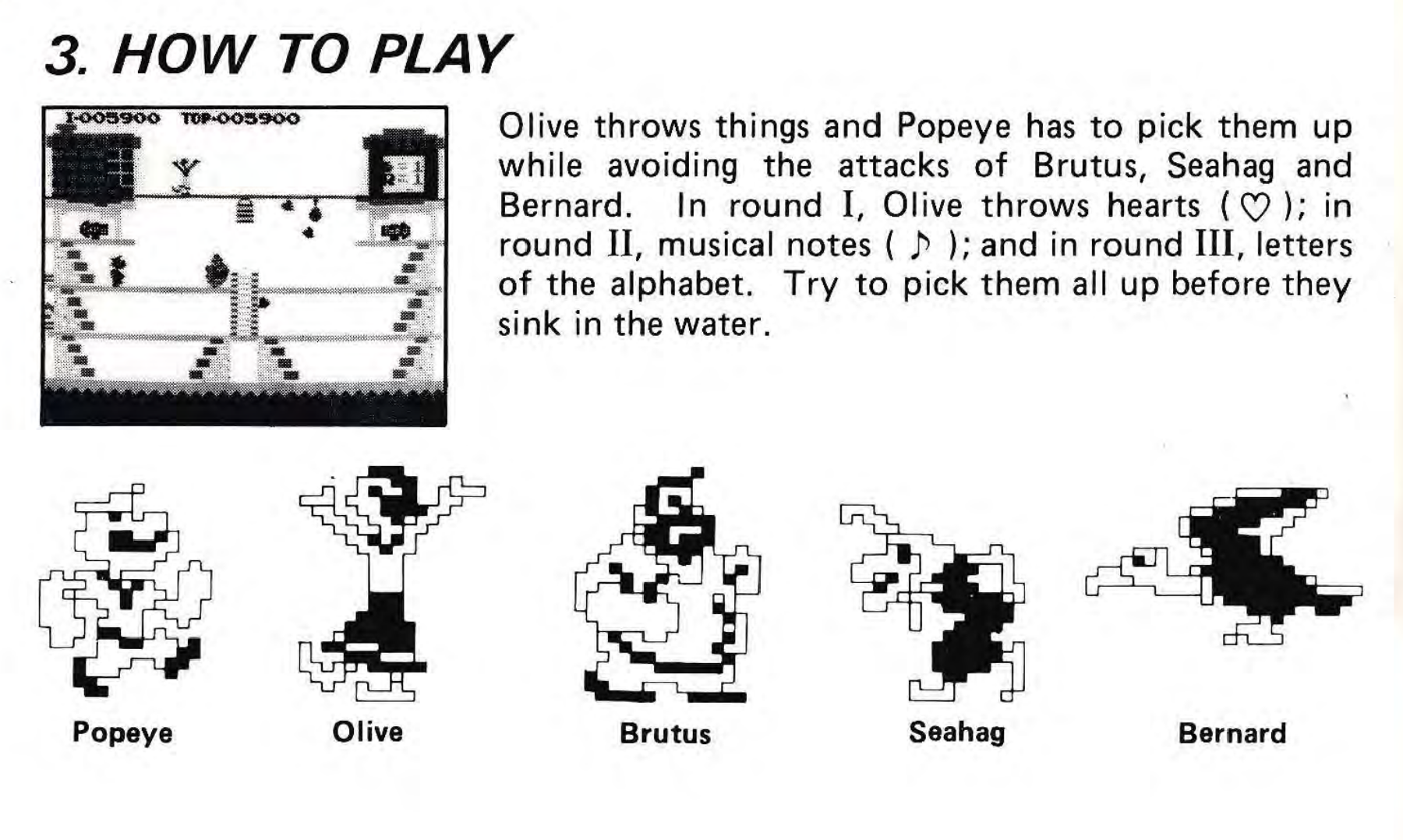

The following year, perhaps due to its demonstrated ability to turn out a smash hit with Donkey Kong, Nintendo did get the approval to use Popeye and friends in a new arcade release. And in July 1983, a port of that arcade game was one of the three launch titles available for the Famicom, alongside Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr., suggesting a certain shared genealogy. I never played the NES Popeye and never saw the original arcade version in action until doing research for this post. That’s too bad, because it’s a gorgeous game, with the sprites for these characters looking much bigger and better than those for Mario and Pauline in Donkey Kong; Popeye, Olive Oyl, and company actually look a great deal how they’d look in a non-pixel-art format

The Game & Watch Popeye came out in August 1981, just a month after Donkey Kong hit arcades, so Iwata is correct when he mentions the inconsistency in what King Features was willing to let Nintendo do with its characters and on which platforms.

Today, Nintendo’s Popeye games are all but forgotten, even if they once held celebrated places in the company’s canon. I assume Nintendo could work out an agreement with King Features to re-release them in some form; it just hasn’t happened, thanks to one or both parties. But this is also the reason I’d guess that Popeye hasn’t been featured in a Smash Bros. game, even if they’d actually be a pretty good fit for him.

To go back to the live-action Popeye movie for a second, I do wonder how much its perceived failure might have soured King Features on licensing out Popeye. Had the movie made more money at the box office — and had the company been riding high when Nintendo approached the company the first time to ask about making a Popeye video game — might it have said yes? If so, the complete history of Nintendo would have been rewritten: With the Popeye license in the bag the first time, there’s no need for Miyamoto to invent Donkey Kong and Mario. If more moviegoers had said yes to Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall doing their best impressions of cartoon characters, the most famous video game character might not exist and the entire industry might be different today.

Popeye is (indirectly) responsible for the concept of power-ups

Just reading the subhed for this section, you might be able to guess where I’m going with this one. And yeah, it’s what you’d think.

Power-ups are such a popular concept that people who do not play video games can still understand the reference. It’s passed into the mainstream lexicon. As a term, power-up is considered an example of wasei-eigo, or Japanese terms built from English loanwords. (Anime, a term formed from the English word animation, is maybe the wasei-eigo most widely known to English speakers.) Power-up, as a noun referring to the video game concept, was created as a separate piece of syntax to the English verb phrase power up — as in, “I need to power up the electric drill if I’m going to use it later.” And while sources are not clear on the official first usage of this term, most agree that it originated in reference to video games as the Japanese term パワーアップ or pawā-appu, made from Japanese renderings of the English words power and up.

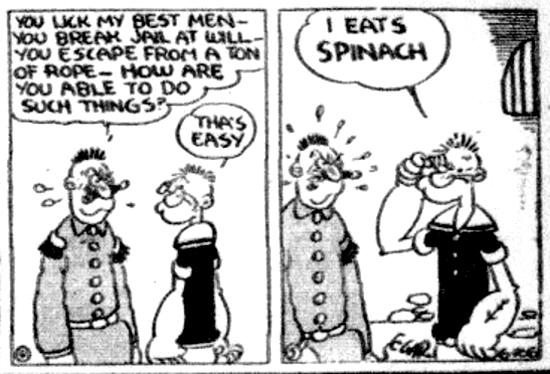

Regardless of when the term was becoming familiar with gamers, the first video game to feature a power-up is most likely Pac-Man, which debuted in Japanese arcades in 1980. Tagging the power pellet allowed players to turn the tables on the ghosts and at least temporarily send them back to where they came from. In my piece on how hockey pucks got wrongly tangled up with Pac-Man, I reference Pac-Man: Birth of an Icon, the superb 2021 book on the character and the game. One section in this book has designer Toru Iwatani explaining how Popeye cartoons provided a major inspiration, noting that the concept of the pursued character turning the tables and becoming the pursuer came from Tom and Jerry, but the idea of a specific item causing that turn to happen comes from Popeye. “In his normal state, Popeye is a delicate character who always loses to Bluto,” he says. “However, once Popeye eats a can of spinach, his position turns around and he unleashes superpowers to throw the big man Bluto. Pac-Man and his power treats are basically Popeye’s spinach.” A later caption makes the relationship more explicit, saying that Popeye’s spinach gimmick “came to define the character and also inspired Pac-Man’s ‘power up’ state.”

Pac-Man first hit arcades on May 22, 1980, and unless I’m overlooking an example that came in between, the second game to use a power-up is Donkey Kong, which was introduced to arcades on July 9, 1981. In the latter game, the hammer functions a lot like the power pellet, in that it allows Mario to take the offense against Donkey Kong’s barrels. It doesn’t make him invulnerable, however, so in the second instance of the power-up’s existence, the concept has already evolved slightly. It would continue to do so: The mushroom in Super Mario Bros., for example, isn’t temporary, and Mario keeps it until he’s damaged by an enemy. In Mega Man, you earn a power-up in the form of getting to use the powers of every vanquished Robot Master, but there’s no physical object that needs to be obtained.

Over the course of four decades, the notion of what a power-up can be has changed a lot. However, because all of them, in all their myriad forms, descend from that original power-up in Pac-Man, and because the power pellet descends from Popeye’s can of spinach, Popeye kinda sorta gets credit for all of them. Like I said in the first section, Popeye being indirectly responsible for the creation of Mario, Donkey Kong, and Pauline is a big deal, and it makes sense that this is the video game connection people know best. However, I’d wager that the power-up thing is an even more important contribution. Without Mario, we wouldn’t have Mario games and all the innovations they’ve given to the rest of the medium. Without power-ups, however? While this basic idea would have materialized in one form or another at some point, without it hitting the way it did back in the day, the whole of video game history could have played out differently.

And yes, BTW, Popeye does get his own power-up in the arcade game, and yes, it’s a can of spinach and yes, tagging it does make the “I’m Popeye the Sailor Man” theme play in the same way touching the hammer in Donkey Kong makes the hammer theme play.

But there’s also one strange thing worth noting: Initially, it wasn’t spinach that gave Popeye his superpowers but instead Bernice the Whiffle Hen. In a June 1929 series, rubbing her head made Popeye invulnerable to bullets, although it’s not explained how or why.

Eventually, Bernice was phased out and by 1931, spinach became Popeye’s secret weapon, his anti-Kryptonite. The following three panels document Popeye’s growing affinity for spinach, and they’re all from the same page on the website Superheroes Eating Food, which I did not know existed but I’m glad it does.

Of course, Popeye’s iconic spinach sequence — gulping it down, the theme song playing, the power-up effect — didn’t become part of his persona until his first cartoon in 1933. It’s worth pointing out that this piece suggests that the sequence may have influenced the transformation sequences that would become common in anime. I’m willing to bet that it’s possible, though Billy Batson, the superhero previously known as Captain Marvel, might have a claim to that legacy too. For the moment, I’m comfortable giving Popeye power-ups and leaving it at that.

If, after reading this far, you find yourself asking, “But why spinach?” I’m still not sure, after reading lots and lots of information about Popeye. There’s a popular urban legend that a wrongly placed decimal point caused the belief that spinach is especially rich in iron, but it’s apparently not true. Even then, Popeye never extols the virtues of spinach as a source of iron. In the above panel, he says it’s good because it’s rich in vitamin A… which is one of the things spinach doesn’t actually have. If you know why Popeye eats spinach over any other possible healthy vegetable, please let me know.

Popeye has another (possible) Mario connection via a men’s fashion magazine

The character of Popeye debuted in E. C. Segar’s Thimble Theatre comic strip on January 17, 1929. Initially a supporting character, Popeye proved popular enough that he became the focus of the strip, with the name eventually changing to Thimble Theatre Starring Popeye and then, beginning in 1970, just “Popeye.” And while the character would enjoy popularity all over the world, he resonated in Japan differently.

This is perhaps especially surprising if you look at Popeye’s use in anti-Axis propaganda — in particular, the 1942 short “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap,” in which Popeye single-handedly fights the Japanese navy, rendered in the kind of offensive caricatures you’d expect from this sort of thing.

By June 1959, however, western Popeye cartoons were airing as part of the Fujiya no Jikan timeslot sponsored by the Fujiya candy company. These airings proved very popular, and viewership of Popeye rivaled or sometimes even outpaced that of popular Japanese cartoons.

This fame endured after Popeye was swapped out for Ghost Q-Taro in 1965. For example, a 1978 disco rendition of the Popeye theme — by a band called Spinach Power, no less — proved to be a hit, and the song then has apparently endured at baseball games in a way that seemed to parallel how “Y.M.C.A.” has lived on in the U.S., despite that song’s subject matter

By 1986, Popeye was the spokesman for Hitachi, selling refrigerators that, yes, can be used to store spinach.

And in 1989, he and Olive Oyl starred in a Suzuki ad featuring the pair taking a romantic sunset drive.

Now, a lot has been written about the ways in which Japan shifted its national identity following World War II. One of the ways this happened was through embracing pop culture — sometimes its own, sometimes reinterpreting stuff from other countries — and then sending its pop culture back out into the world in the form of movies, cartoons, comics and, of course, video games. This process has been the subject of many books, articles, and essays. Somehow Popeye got wrapped up in all this, and as a result, he ended up achieving a level of popularity in Japan that he hasn’t enjoyed in the U.S. in my lifetime, and I suspect never has. In short, he got cool. You’ll see his name on everything from a beer club in Ryōgoku to a sex shop in Shinjuku’s gay district.

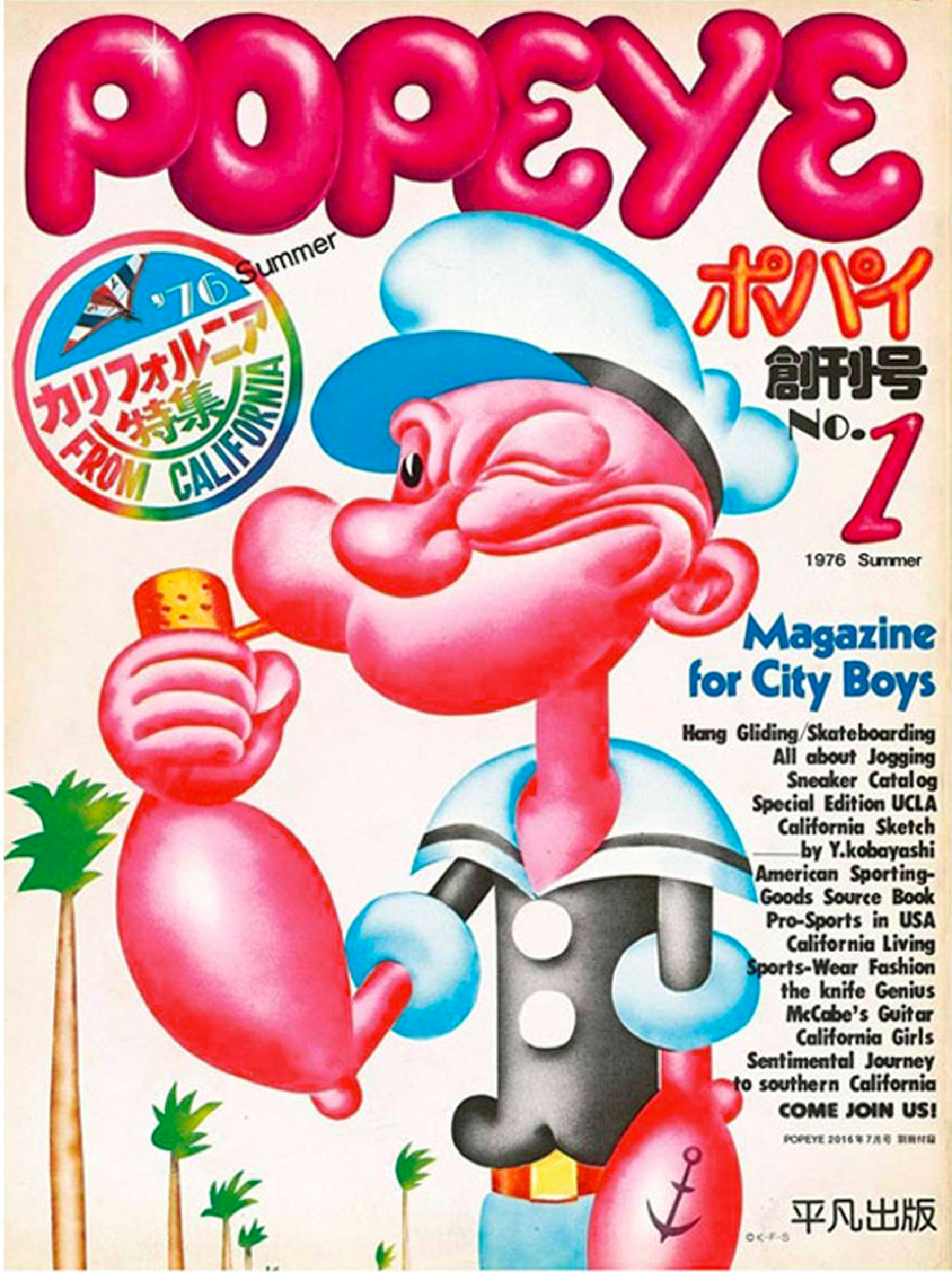

The most surprising example of Popeye’s upward mobility in Japan, however, would have to be the long-running magazine Popeye — a publication that has been advertising itself as a must-read “for city boys” since July 1976.

If you are just learning of this publication’s existence right now and feeling like Popeye is not the first character you’d expect to be namechecked by a magazine that aims to appeal to hip, fashion-savvy urbanites, you’re not alone. It’s explained in this post and backed up by this 2016 L.A. Times piece that the name is both a reference to the character and a play on the idea of it (and its readers) having an eye on all things pop. What’s more, the extended Popeye magazine family also includes Brutus (and I’ll get to the business of Bluto vs. Brutus in the miscellaneous notes section) and Olive, a women’s magazine that shuttered in 2003.

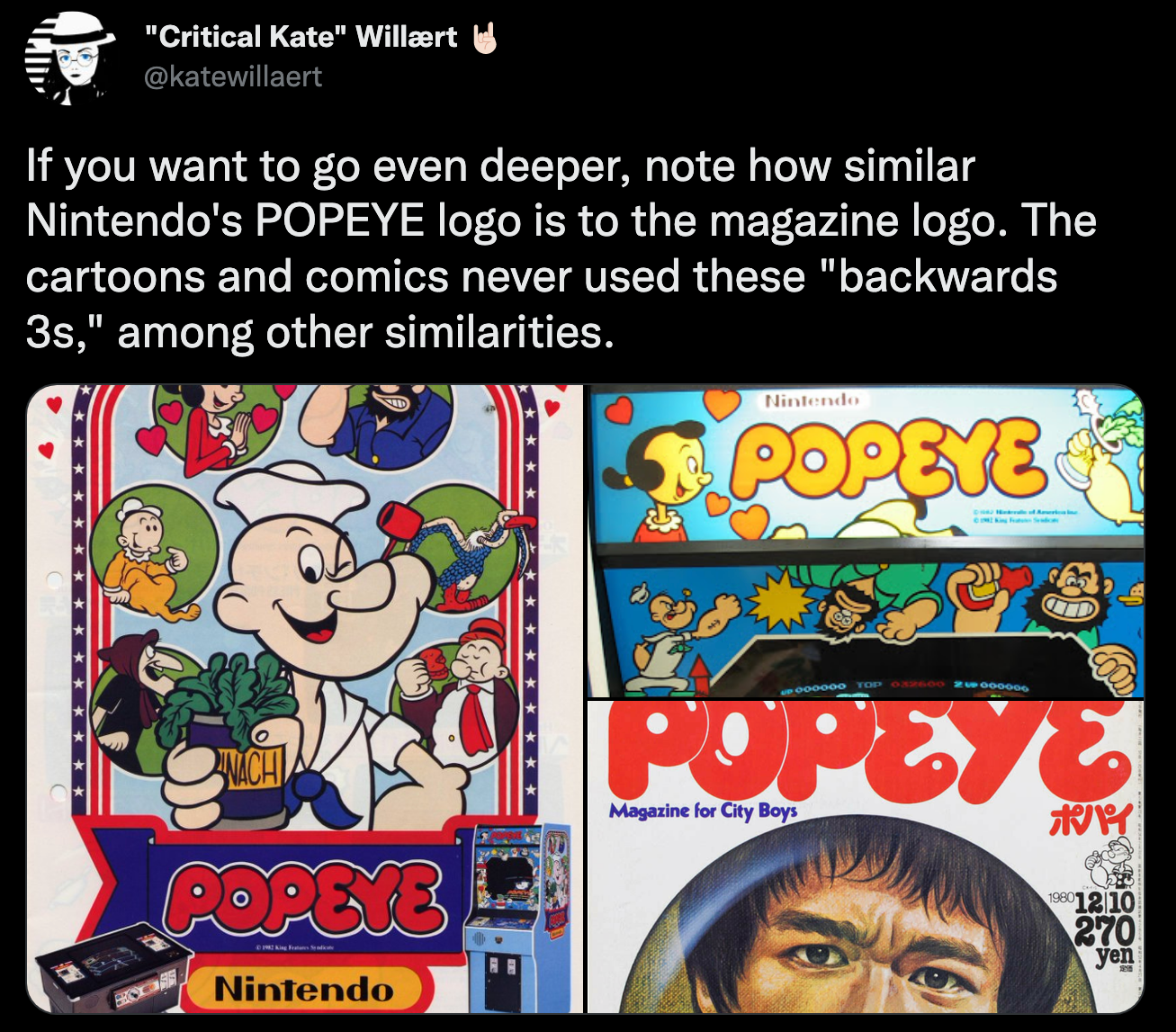

Back in 2020, the gaming history writer Kate Willaert pointed out a rather curious cover to one of Popeye’s March 1980 issues.

The resemblance, as Willaert points out, is striking. It’s not Mario, exactly, but it is a guy with a mustache. He’s smiling broadly, in that Mario way, and he’s wearing blue overalls and a red shirt. Could it be that Shigeru Miyamoto had seen this magazine cover and then drew upon it, consciously or not, when he was creating Mario? It’s possible! Though it might seem to conflict with the story that Nintendo usually tells about how Mario ended up looking the way he did: to look good while moving given the technical limitations of the programming.

It’s a story that has been told and retold many times, but the version I’ll point to is a 2015 NPR interview with Miyamoto in which he says, “When we first drew [Mario] in Donkey Kong, he was drawn using pixel dots in a 16 x 16 grid. So it was a very small space in which to draw the character, and it was a very small character on the screen. And so in order to emphasize the unique characteristics of the character, we made the big nose and the mustache and the overalls to make it easy to understand what the character was doing on the screen.” The overalls, for example, give Mario’s arms a reason to be a different color from the rest of his body, which allows him to show off movement. And the mustache breaks up the pixels forming Mario’s face in a way that reads better than if they’d tried to give him a mouth back in the day.

Does this official explanation discount Willaert’s theory? I really don’t think so. Sure, the technical reasons prompted Nintendo to make certain choices over others, but it’s also possible that Popeye magazine could have been the thing that suggested the solutions Miyamoto was looking for — and until he says that definitively no, Popeye had nothing to do with it, I’m going to hold out hope that this might be the case.

Given that Willaert was somewhat easier to get a hold of than Miyomoto, I asked her how she came to find this particular issue of Popeye. “I was trying to figure out what sort of Popeye media existed in Japan around the time Donkey Kong was being developed,” she said. “After I discovered the magazine, I started digging in further. I was browsing covers trying to get a general sense of what ‘city boy’ fashion was, and when I saw that one particular cover my jaw dropped.”

For what it’s worth, she thinks she might really be onto something: “My fellow historians are mixed on whether it’s a solid connection or mere coincidence. Some roll their eyes anytime it’s brought up, lol. But personally, I’m in the ‘solid connection’ camp. I think Miyamoto wanted to create a similar working class type character as Popeye, but without the baggage of trying to capture a likeness. I think maybe he saw that cover and realized, oh yes, overalls and a mustache would translate really well to pixels. But I’m not sure if we’ll ever see actual confirmation on that.”

Until someone asks Miyamoto, of course, and I’ll be impressed at the person who actually gets a few minutes of the man’s time and chooses to spend them on Popeye magazine. However, Willaert has one more connection between Nintendo and the magazine. The bubble letter font that Nintendo uses for its game versions of Popeye is modeled on the Popeye magazine nameplate. The design of the “E” is particularly unusual, in that it looks like the numeral 3 backward.

No American logo for anything Popeye-related logged on this font history site has looked anything like that. It’s unique to Japanese permutations of Popeye, and it appeared on the front of the magazine first. So at the very least, someone at Nintendo had Popeye magazine on their mind, regardless of whether it was Shigeru Miyamoto.

These are the three ways I can think of that show how Popeye has had a lasting effect on video game culture. They’re all indirect ways, I realize, but that’s kind of the point. We don’t really think of Popeye as being a major player in video games today, because he’s not, but his influence was once so great that he could help shape things that we think of as being fundamental to the medium.

It’s entirely possible that you may know of more ways other than these. If so, let me know, and I’ll update this post.

Miscellaneous Notes

Some time after this post went live, I did one about the lesser-known Mario character Foreman Spike, who serves as a sort of predecessor to Wario. Wario’s creators have said on the record that Bluto inspired Wario, and I’m willing to bet that because Spike and Wario have so much in common, Bluto inspired Spike as well. Read that post here.

Technically speaking, the bad guy in the Nintendo Popeye game isn’t Bluto but Brutus, an essentially identical character invented to circumvent a legal snafu that, in the end, did not actually exist. Brutus was invented for the 1960 animated series Popeye the Sailor because at the time, it was believed that Paramount Studios, which produced the original Popeye shorts, owned the rights to Bluto. This turned out not to be the case; Bluto was created by E. C. Seegar for Thimble Theatre in 1932, meaning King Features owned the rights to him all along. In some later adaptations, Brutus was retconned to be Bluto’s brother. But ever since, there has been a Berenstain Bears–-style memory hole in pop culture about what the name of Popeye’s hunky archenemy actually is. To make matters more confusing, there is also a third brother — Burlo, a beardless variation on Bluto. Rendered in katakana, Bluto and Brutus’ names look even more similar: ブルート (Burūto) and ブルータス (Burūtasu).

The Popeye arcade game also features the Sea Hag as a minor antagonist. I’m pretty sure this makes her the first female villain in a Nintendo game.

Though today known as Popeye’s girlfriend, Olive Oyl actually predates Popeye by more than a decade. She debuted in the first Thimble Theatre comic strip, which ran on December 19, 1919, and was the main character before Popeye showed up.

At one point, this post was going to have a fourth section about Robin Williams — who played Popeye in the live-action film — being a longtime lover of video games, to the point that he named his daughter after Princess Zelda. I could swear I remember learning that Williams fell in love with video games in Malta, during downtime on the set of the Popeye movie, and I cannot find this anywhere. If you know where I can find that article, please let me know.

If the Nintendo arcade game Popeye had, in fact, been based on the live-action film, it would have been the second video game ever to be a movie tie-in, the first being Star Trek: Phaser Strike, released in 1979 for the Milton Bradley Microvision in promotion of Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Not only does King Features own Popeye but also many comic strips, including Blondie, Beetle Bailey, Hagar the Horrible, Flash Gordon, Prince Valiant, The Lockhorns, The Phantom, and Rex Morgan, M.D. Curiously, King Features also has its hand in Cuphead — not the video game but specifically the animated adaptation made for Netflix. King Features produced it, and its president, CJ Kettler, is an executive producer on the show.

While Donkey Kong is often credited as the game that solidified the platformer genre and sometimes even the first platform game ever, the 1980 Universal arcade title Space Panic is considered by others to be the first, even if it lacks a jump button and even if it was, at the time, considered an example of the “climbing game” genre.

One pop culture entity that does not apparently owe a debt to Popeye? The Popeyes chain of fried chicken restaurants, which is apparently named after Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, Gene Hackman’s character in The French Connection. No, I don’t know why either. Popeye (the cartoon character) has appeared in promotions for the restaurant, but it’s an association that was only made after the fact.

Just as the U.S. used cartoons as propaganda, Japan did as well, and the 1943 short Momotaru’s Sea Eagles features cute animals bombing Pearl Harbor. While the poster for the film features Popeye, Bluto, and Betty Boop alongside Franklin D. Roosevelt, the film itself only features Bluto, presumably representing a caricature of an American sailor.

Among the other major animation stars not to appear in Who Framed Roger Rabbit were Mighty Mouse, Little Lulu, Casper the Friendly Ghost, and Tom and Jerry. You can see storyboards for a never-realized funeral scene in which Popeye served as a pallbearer for the murdered studio exec at the crux of the film. Of course, he gets in a fight with Bluto.

In 2021, Ajinomoto produced a commercial featuring an animated Popeye and a live-action Olive Oyl… who, upon saying the tagline “Let’s olive!” transforms into a bottle of actual olive oil, but later we see her eating the finished meal, so I guess she eats herself? For what it’s worth, actress Ayami Nakajo makes a decent Olive Oyl. You know, before she transforms into food.

Unless I’m mistaken, Popeye hasn’t been featured in a commercial of note in the U.S. since 2001, when a Minute Maid commercial seemed to be making the case that Popeye and Bluto were a couple and that drinking orange juice made them gay. It caused a minor commotion back in the day, mostly because it’s the gayest commercial anyone had seen in a long time. Like, I host a podcast called Gayest Episode Ever, so I think I have some authority on this, and it’s very, very, very gay.

Finally, the Who Framed Roger Rabbit podcast episode I mentioned at the top of his post was part of What a Cartoon, itself a spinoff from Talking Simpsons, which I’ve been on a few times. The monthly movie deep dives are a Patreon-only feature, though I would suggest it’s worth the small monthly fee if you love cartoons, and you can listen to a preview of the episode here.

EDIT: In researching this post, I bought a reproduction of the first issue of Popeye magazine. As a native Californian who has lived in Los Angeles for the past decade, it was a trip to see a not-that-long-ago version of SoCal culture get celebrated by another culture. If you want to see my highlights of my flip-through of Popeye magazine’s issue number one, I have posted them in a thread on Twitter.

Magazine for City Boys!