Esper, Eidolon, Eikon, Aeon: The Evolution of Final Fantasy’s Summoned Monsters

Every few years, I recall the fact that Akira the anime was adapted from a much longer manga, and I get to wondering about what all is missing from the movie version. This never motivates me to read the actual manga, however. I just read a summary of the longer version of the story, which means I will forget the details almost immediately, ensuring that at some future date this will all happen again.

During the most recent iteration of this cycle, I was reminded that the English localization of the manga uses a curious term to refer to the three creepy psychic children: Espers. The primary context I have for this term is Final Fantasy VI, the English localization of which uses it to refer to a kind of summonable monster that wields magic. Though creatures like these had been a part of the franchise since Final Fantasy III, we didn’t know this in the west because the only other game translated into English back in the day was Final Fantasy IV. Its first localization referred to this class of creatures as Summon Monsters, which I think we can agree lacks a certain spark. When the English version of Final Fantasy VI called them Espers, I assumed it was a correction and that this is how they were known in Japan and how the series would refer to them moving forward.

I was wrong on both counts, however.

Final Fantasy VII would call them Summons. Final Fantasy VIII would call them Guardian Forces. And Final Fantasy IX would call them Eidolons. What’s more, these English terms frequently have no bearing on what they’re called in Japanese, which does not change from game to game nearly as much as their English counterparts do.

Maduin, an Esper in Final Fantasy VI and one of the few summoned beasts in the entire series that the player can control as if he were a playable character.

There’s something in this that intrigues me because it connects to a larger idea. What might seem like inconsistent branding is actually representative of the human inability to discuss the metaphysical other — something here from somewhere else, something that is not human and is not beholden to our laws. Some religions spend a lot of time trying to get their adherents to understand a specific notion of intelligent life that is not human, and in more than one instance, two different ones end up offering wildly divergent conceptions of what seems like the same thing.

I know I’ve jumped from Akira to Final Fantasy to world religion already, but I’m going to do it again and bring in a sitcom, of all things. The second episode of the classic series Bewitched features a line that describes the otherworld a lot more beautifully than I think most of us would expect from TV comedy. Endora, an elder witch, is trying to convince her daughter to abandon the dull human she’s married and return to the realm of witches. This is how she describes that which is seemingly beyond language:

We are quicksilver, a fleeting shadow, a distant sound. Our home has no boundaries beyond which we cannot pass. We live in music, in a flash of color. We live on the wind and in the sparkle of a star.

I truly love that, especially the way Endora uses abstractions to limn an existence for which English seems to lack words. Maybe any human language would fail to describe this, because we’re bad at naming what we can’t even perceive.

By design and by accident, the Final Fantasy series has mirrored this in the multiple ways it refers to its summoned monsters, who teleport into battle to launch a single attack before returning to the unseen dimension from which they came. With the English localized names especially, it’s almost as if no one single term can fully convey what they are, though each manages to convey an aspect. And it’s for this reason that I wanted to look at the evolution of how we’ve referred to these creatures since their debut.

In the original Japanese version of Final Fantasy III, these creatures are called 幻獣 or Genjū, which is usually translated in the context of this series as “phantom beast,” but the kanji 幻 can also be translated as “illusion,” “fantasy,” “dream” or other similar terms. Outside the context of Final Fantasy, genjū is sometimes translated as “mythical beast” or even “cryptid,” and these both make sense too, seeing as how the majority of the creatures appearing in any given Final Fantasy title are drawn from mythology and folklore. Whatever the translation and perhaps because it can draw together such a great many meanings, this name remained as the Japanese way to refer to them for a long time. In fact, in my head, it’s the default, even if the newer games use something different. English, meanwhile, changes the name more often, and I think it’s interesting how so many different localizers have come up with neologisms attempting to convey what’s packed into this original Japanese name.

As I said before, the original English version of Final Fantasy IV would seem to whiff it pretty hard by calling them Summon Monsters, though this name at the very least gets across the point that they come when you call them. Maybe the biggest problem with the term is that while some of them fit the western conception of what a monster should look like, others are downright humanoid. I assume this is why starting with the PlayStation localization, they’re just called Summons, which in the wake of Final Fantasy VII had become a standard way to refer to them in English.

Ramuh, the lightning-elemental summon from Final Fantasy IV, looking more or less human.

Asura, queen of the summoned monsters in Final Fantasy IV, looking considerably less human.

Leviathan, king of the summoned monsters, looking not human at all.

Final Fantasy IV also fleshes out the lives of these creatures when they’re not in battle. They have a town they live in, and presumably they’re spiriting to and from here when Rydia, the game’s sole summoner, is requesting their presence. In the original Japanese, this location is 幻獣の町 or Genjū no Machi, literally “Town of Phantom Beasts.” In English, it’s Land of Monsters and then Land of Summons, but for the Nintendo 3DS remake, it’s given a proper name: the Feymarch, which I was surprised to learn is unique to the game. In an interview with RPGamer, localizer Tom Slattery explains how he came up with it.

Every other Final Fantasy had given them a name — Espers, Eidolons, Guardian Forces — but Final Fantasy IV simply called them summons or summoned monsters. … [I] felt the creatures’ world deserved a proper name. Who would call their own realm the Land of Summoned Monsters? And hey, inventing words is always fun. Feymarch had zero Google hits before the game came out; now it has tens of thousands.

He doesn’t say so, but the term would seem to be at least partly inspired by the Feywild, the faerie plane in Dungeons & Dragons, fey and fay both being English words whose etymologies are complex tapestries of death, fate and fairies, the otherworldly, the paranormal and the enchanted.

There’s not much to discuss regarding Final Fantasy V. The game didn’t get an English version for years, and when it finally came out, it sucked, famously referring to the Wyvern enemy as Y Burn, among many other localization sins. For what it’s worth, this and all subsequent English versions of Final Fantasy V have referred to the creatures in question as Summoned Monsters or Summoned Beasts. It’s Final Fantasy VI where things get interesting. While the Japanese version retains the tried and true Japanese name, Ted Woolsey’s English translation calls them Espers.

In the game, these creatures live in a universe parallel to the one of humans and also off-limits to visitors, as the Espers fear having their magic powers abused. The Japanese name for this place is very similar to the one in Final Fantasy IV: 幻獣の村 or Genjū no Mura — literally “Village of Phantom Beasts.” In English, it’s the Esper Realm or Esperville, which at the very least tells English-language players that this group of monsters is different from those that have appeared before. Unlike their counterparts in previous games, they don’t just refer to themselves by their relationship to humans; they have a proper name to refer to themselves.

Terrato a.k.a. Midgar Zolom a.k.a. Midgardsormr, a recurring summoned beast debuting in Final Fantasy VI.

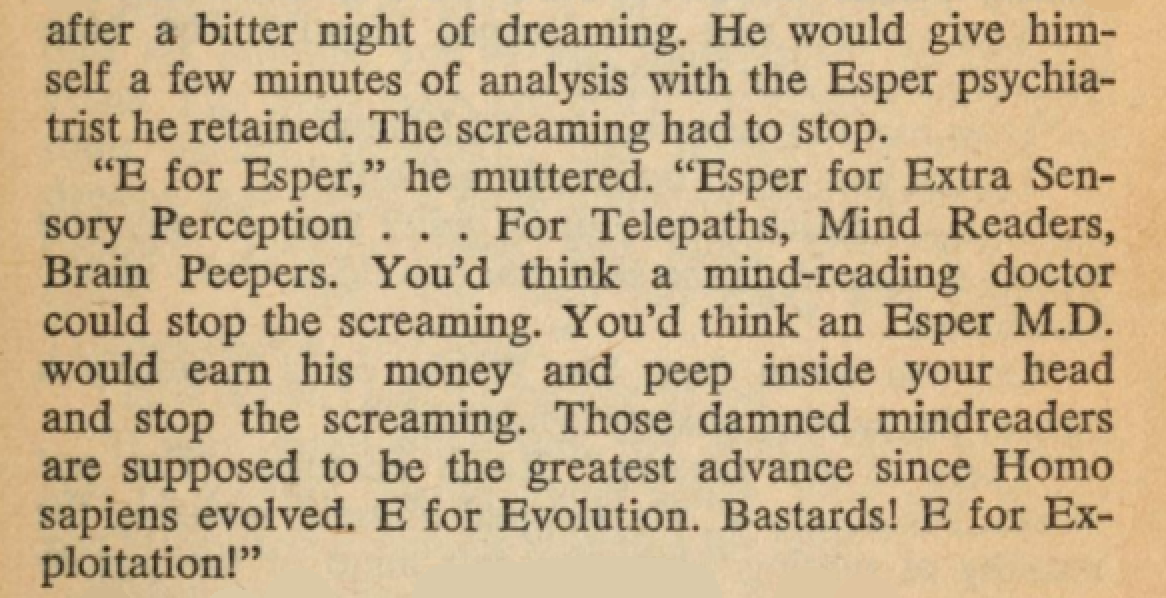

The origins of this term esper, however, are murky. The oldest usage of it in print that we can find is in the science-fiction short story “Oddy and Id” by Alfred Bester. First published in the August 1950 issue of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, it tells the story of scientists investigating a young man who seems to have preternaturally good luck. But if you actually read the story, Esper is used in a casual, off-hand manner that doesn’t necessarily make it clear what it’s supposed to mean. To me, this passage reads like the author would have expected the reader to understand the term, which makes me think it must have appeared in print before this.

The passage in question, reprinted in the 1975 short story collection Strange Gifts.

Bester used the term again in his 1953 novel The Demolished Man, a detective story taking place in a future in which telepathy is commonplace. On second reference, he makes it clear how he’s using the word. Possibly the audience for sci-fi novels was different from the one that bought sci-fi magazines, but also maybe the publishing company paired him with an editor who pointed out that this is not a word everyone would know.

Both Bester’s uses would seem to corroborate the suggested etymology that the term comes from the abbreviation ESP, in that someone who has psychic abilities is an “ESP-er.” (The use of ESP as a shorthand for “extrasensory perception” goes back to at least 1934, in case you’re wondering.) In fact, some renderings of the term in the English localization of Akira are styled to emphasize this — ESPer rather than Esper — and that would make sense given that these children are defined by having their paranormal powers. For reasons I can’t pinpoint, it seems that this term has caught on more in Japanese pop culture than it did in any English-speaking region. The series Mami the Psychic, for example, is called エスパー魔美 (Esupā Mami) in Japanese, the mascot for the Toshiba company is a character named 光速 ESPER (Kousoku Esper or “Lightspeed Esper”), and the Japanese title for the British series Misfits is ミスフィッツ-俺たちエスパー! (Misufittsu: oretachi esupā! or “Misfits: We’re Espers!”).

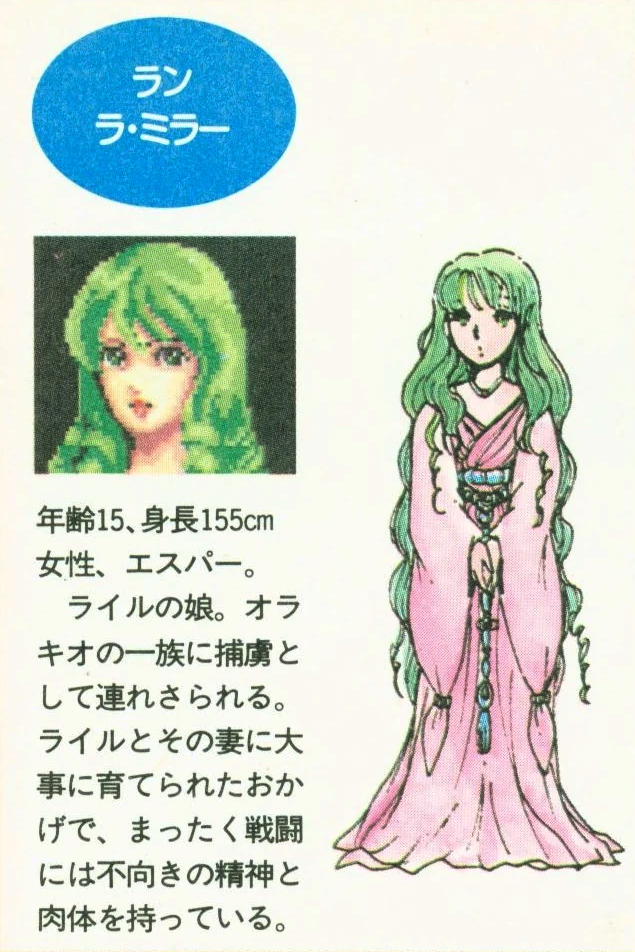

This wider Japanese use of the term does not exactly line up with the idea of the legendary beasts and full-on magic users in Final Fantasy, though I suppose moving from people with psychic powers to people with magic powers isn’t really that much of a stretch. A character who has pyrokinetic abilities in a sci-fi context might just seem like a fire magic-user in a fantasy one, after all. And it’s perhaps worth mentioning that the Phantasy Star series of RPGs, which takes place in a world that combines sci-fi and fantasy elements, uses the term for a certain kind of mage-type character.

Meet Thea, one of many Espers appearing in the Phantasy Star series. (Note the katakana “エスパー” appearing in the second line.)

As near as I can find, Woolsey has never stated on the record how he arrived at calling the Final Fantasy VI creatures Espers. It’s one of many questions I’d ask him if I ever got the opportunity, but until that happens, I can only point out a common analysis of the term used in this particular context, and that’s its similarity to the French espérer, “to hope,” as well as many other Latinate words meaning similar. Magic may destroy the world in Final Fantasy VI, but it also ultimately gives the heroes a chance to save it.

Neither the Japanese nor the English versions of Final Fantasy VII gives a special name to the summoned beasts. In fact, their existence goes oddly unexplained in this game, though some cut dialogue gives the vaguest of backstories. What’s interesting here is that the game refers to this class of creatures as 召喚獣 or Shōkanjū, meaning “summoned beasts,” which is a departure from what they’d been called in Japanese since Final Fantasy III. For whatever reason, the localization team decided not to re-use Esper or come up with a new name, instead just sticking close to the Japanese original.

Perhaps as a reaction to the relatively little attention paid in Final Fantasy VII, the summoned beast figures more centrally into the plot of Final Fantasy VIII. Both the Japanese and English versions rebrand it as Guardian Force (ガーディアンフォース or Gādian Fōsu). I suppose a name that was essentially English already meant there was no need for anything new on the localization team’s end. Besides, it makes sense in any context to call them something new because in several key ways they function differently than their counterparts in previous games never did. In either language, however, I have to say that this name sounds less like an attempt to describe an mystical other and more like a branding exercise; in fact, Guardian Force sounds like a game mechanic, I guess because it is.

While Final Fantasy IX is in many ways a throwback to the first six titles in the series, the Japanese version makes the odd choice of bringing back Shōkanjū instead of Genjū. The English version, meanwhile, introduces a whole new element into the series by calling them Eidolons, which you may be shocked to learn is actually a real English word, if an extremely obscure one. The word can mean “an idea” or “an ideal form,” but the sense that I’m guessing got it picked for a Final Fantasy entry is the third definition: “a phantom,” which puts it closer to the original Japanese “phantom beast” term than the Japanese term actually used in this particular game.

Carbuncle, looking more monstrous in Final Fantasy V than he’d look in basically any subsequent game.

According to Etymonline, eidolon comes from the Greek word meaning “appearance, reflection” and then from there “mental image” or “apparition.” These suggest to me a sense that had been hinted at but not explored explicitly before; rather than being extant beings summoned from a faraway realm, perhaps they’re the user’s own projections, pulled from within, where they’re encoded into the brain not unlike Jungian archetypes. Enticingly, the Greek eidōlon is also the source of our word idol, which brings into the mix associations of false and lesser gods, which is how Abrahamic religions often regard the entities whose existence they can’t or won’t explain. As a Final Fantasy term, Eidolon was reused for the more recent remakes of Final Fantasy IV as well as in Final Fantasy XIII and its sequels.

Final Fantasy X puts summoned beasts to the forefront again, as much of the game’s story centers on Yuna, a summoner. And while the Japanese game uses Shōkanjū to refer to these creatures, the English version picks another new term: Aeon. To me, it makes sense to introduce a new name because this version of the summoned beasts is yet again radically different from previous versions. That new name might look just like a gussied-up version of our word eon, and indeed it might just be that, because a lesser-known definition of the word is an entity purported to exist in various gnostic philosophies. I will be honest; I read more about gnostic aeons than I expected to, yet I still don’t understand exactly what they are. That may be the point, even if the gnostic aeons are meant to be somewhat more comprehensible, nameable manifestations of a supreme deity that is otherwise impossible to describe. That’s enough, I suppose, to make them make sense in this essay, and I’ll even point out that this puts them in opposition to Eidolons in the “false god” sense, as Aeons are implied to come from the one unknowable creator entity.

The Final Fantasy XI term for the summoned beast is Avatar, and I should say that it’s more in the Hindu sense of the word rather than the mundane way we use it in English today. Do people realize that this word we use so often in online contexts comes from the Hindu concept of a god manifesting on earth? It’s sometimes in human form specifically, but technically the Sanskrit term, अवतार or avatāra (literally “descent”), refers to making the intangible tangible, so in that sense it’s actually very close to the gnostic aeons being a way to present an aspect of a god too great to be perceived all at once. I think it’s a striking use of what might otherwise seem like too ordinary a name for these fantastic creatures. The Japanese version of Final Fantasy XI, meanwhile, just terms them 神獣 or Shinjū, literally “divine beasts.” It gets the point across, but I actually prefer Avatar, considering what its etymology brings to mind.

Final Fantasy XII brings back Esper, and then Final Fantasy XIII brings back Eidolon. In Final Fantasy XIV, we get multiple terms for summoned creatures — or at least that’s my understanding, as this is a game I’ve not played at all. The main term, Primal, would seem to suggest that these creatures pre-date whatever age the game is meant to occur in, and I have to admit that it’s maybe my least favorite of any of the English terms in the series.

Because this installment is an MMORPG and takes place in a larger world, it offers some linguistic variations for its various geographic regions, with Eidolon being one regional term for summoned beasts and Eikon another. A new term, Eikon would seem to come from the Greek eikon, whose meanings range from the mundane to the fantastic: “likeness, image, portrait; image in a mirror; a semblance, phantom image,” according to Etymonline. But icon also captures a sense of the divine, as it can refer to paintings displayed in various Christian churches. Curiously, Final Fantasy XIV introduces an array of names for these creatures in the Japanese version: 蛮神 or aragami (“wild god”), 蛮神 or banshin (“savage god”) and 闘神 or tōshin (“warring god),” according to the Final Fantasy Wiki.

I haven’t played Final Fantasy XV either, and I’d be happy to have had someone who has fill me in on the two classes of summoned beasts in this game: Astrals and Messagers, or in Japanese 六神 or Rokushin (“six gods”) and 二十四使 or Nijūyonshi (twenty-four messengers). At the very least, I would agree with the Final Fantasy Wiki’s entry, which likens the latter group to angels interceding between humans and gods. And then in Final Fantasy XVI, they’re called Eikons once again in English and Shokanjū in Japanese.

When I first began writing this, I intended it to be a short post about the history of the word esper. That may still be the most interesting part, at least on an etymological level, but I do find something profound in the way this long-running series has struggled to express something that humankind has tried to put into words ever since we began wondering if we were alone on this planet. Either because we felt existential dread at the thought of being the only sentient race or because we had the nagging sense that we weren’t, we have come up with countless attempts to name an other that we could never really understand. It may be the reason we’re such inveterate storytellers, honestly, and if that’s the case, then it’s all too appropriate that any given Final Fantasy draws its summoned monsters from world mythology. Each one is a who’s who of our many attempts to imagine a way we weren’t on our own.

After having read all this, It may not surprise you to hear that I am interested in people’s experience of the paranormal — not because I believe any given account necessarily happened, but because it’s worth considering what narrative framework someone uses to tell their story. There’s a theory stating that if a person were confronted with something they could not explain, maybe even something their brain can’t understand because it doesn’t follow the rules of human perception, then they might classify it as a ghost or a demon or a fairy or an angel or a god or a djinn or an alien or a monster, all depending on their background and what their respective culture has conditioned them to see. Imagine that something existing in four or five dimensions showed itself to a human who can only see three dimensions; our brains might just flash an error sign and fill in the blanks with whatever fantastic entity made the most sense to us. And two different people viewing the same ineffable thing might walk away with two different understandings of what they saw. In that vein, it seems possible that the great variety of supernatural entities that have been purported to exist might all have sprung forth from our best efforts to cope with something we can’t understand.

I’m not saying that the evolution of names for Final Fantasy’s summoned beasts is a product of this phenomenon, of course. It’s more that it’s curious how the series wants to rename these creatures again and again, even when they haven’t changed enough from one game to another to merit a new name. At the very least, Final Fantasy’s treatment of them makes a handy metaphor for the real-life phenomenon. And I suppose that in the future Final Fantasy will continue to find new ways to refer to its summoned monsters, always glancing off a facet of what they’re meant to represent but never fully capturing the whole thing, just like how humans’ wildest dreams about an intelligent, sentient other will always fall short.

For culture’s sake, it’s nice that we keep trying.

Miscellaneous Notes

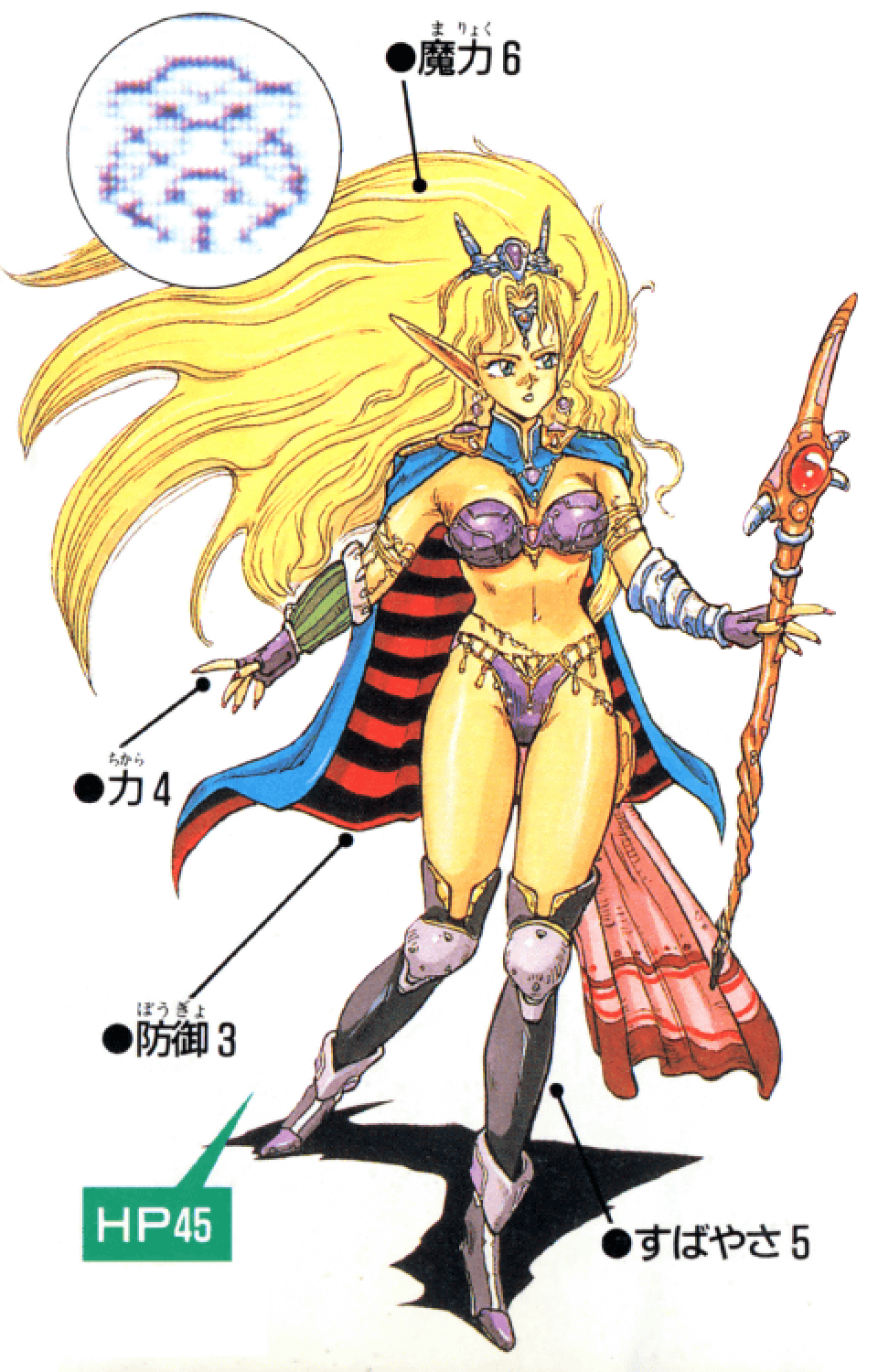

I couldn’t fit it into the essay proper, but it’s also worth looking at the names of the class that’s able to summon these beasts. While the first English localization of Final Fantasy IV dubbed Rydia a Caller, it’s been more or less consistently Summoner ever since, even in games where the action command exists but the class does not. It’s a little more complicated in Japanese, however.

Final Fantasy III splits the class into “beginner” and “advanced” levels, much in the way it does that with the White Mage and Black Mage and their more powerful levels, Devout and Magus. The “beginner” version of the Summoner class is Evoker, the Japanese name for which is 幻術師 or Genjutsushi, “Illusionist.” That’s an interesting name for the class, since the series was at this point 幻獣 or Genjū, which is usually translated as “phantom beast” but can also be translated “illusion beast.” (For what it’s worth, Anna Cairistiona’s essay on this subject translates it as “Conjurer.”) The Japanese version of Summoner, however, hits even harder: 魔界幻士 or Makai Genshi, “Demon World Illusionist,” I guess with the notion that the spellcaster in question is pulling inhabitants from makai, a location that’s come up repeatedly on this blog. By Final Fantasy IV, however, it’s more or less standardized as 召喚士 or Shōkanshi, “Summoner,” with 召喚 or shōkan just being the word for a legal summons or subpoena. It’s stuck ever since, and I suppose it’s surprising then that it took until Final Fantasy VII for the term 召喚獣 or Shōkanjū, “summoned beasts” to become how the game refers to the entities being summoned.

Cairistiona’s history of summoned beasts also notes that various Japanese-language materials for Final Fantasy III also refer to the creatures in question as モンスター or monsuta, “monsters,” and as 冥界の精霊 or meikai no seirei, “spirits of the underworld.” However, if either of these were canon at the time, they didn’t reappear in the series in any significant way.

I’ve written before about how Final Fantasy pulled liberally from Dungeons & Dragons, especially early on, so I was curious to see if Summoners originated there as well. As near as I can tell, Summoners didn’t exist as a D&D class prior to Final Fantasy III, though summoning is a thing that various magic-savvy classes can do in one sense or another. But that leaves me wondering if a class dedicated to this particular form of magic was invented by Final Fantasy or if it’s pulling from somewhere else. I’d assume it’s the latter, given how letting a monster fight on your behalf is kind of the premise of Pokémon and every other Pokémon-like game series out there, but I’m betting someone reading this will know better than I do.

Speaking of the particulars of this class, one of the stranger elements of the Final Fantasy Summoner is the forehead horn, which doesn’t show up consistently. When it does, the horn is sometimes just an ornament (like in Final Fantasy III or any game where you can change a character’s class) and sometimes an actual horn growing out of their head (like Eiko in Final Fantasy IX). I looked around online and couldn’t find any indication that the horn was inspired by any preexisting work. And while I could argue that perhaps this animal part appearing on a human body might represent that person’s connection to nature, beasts and monsters, my gut feeling is that it might actually be a result of the Final Fantasy III programmers needing a way to visually distinguish the Summoner sprite from the others. Like, “We only have so many pixels. I dunno. Stick a unicorn horn on it?”

It’s hard to see clearly in the Famicom version, but the Evoker a horn too, just worn on the back of the head. I’d guess that the advanced version wearing it on the front is something akin to how college graduates move the tassels on their mortarboards from the right to the left during their ceremony. This read of it is possibly confirmed by the remakes, which show that it’s meant to be a sort of headband instead of an actual growth coming out of their head. I’m open to anyone else who has theories on this one, however.

The Wiktionary entry for the katakana rendering esper, エスパー (esupā), guesses that it may be an example of wasei-eigo, a category of… sort of loanword but not, using English words in Japanese but specifically in a way that a native English speaker wouldn’t. Think salaryman or coin laundry, which both make sense in English even if they’re not the terms we actually use. But I’m guessing esper is not a true example of wasei-eigo because the term at one point was used in English.

In fact, my friend Diamond Feit tells me there’s an episode of the original Star Trek that uses the term esper: the third episode of the first season, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” is about crewmembers acquiring psychic powers.

In the same way that the first Seiken Densetsu game was marketed outside Japan as Final Fantasy Adventure, the SaGa series also began on the Game Boy — as 魔界塔士 サ・ガ or Makai Toushi Sa·Ga (“Hell Tower Warrior Sa·Ga”) in Japan but as Final Legend elsewhere. All three Final Fantasy Legend games feature Mutants as one of the main character types, and it actually makes sense that they were called エスパー or Esupā in Japan. They’re more adept at magic, and I suppose then that calling them Mutants in the English version makes a lot of sense, especially considering how popular the X-Men had gotten in North America. In fact, I think this might back up my theory that magic powers and psychic powers might function very similarly, with only the genre of the work affecting whether someone sees them as the former or the latter. Maybe that linkage between the more psychic sense of the term and the magic-using Espers in these games is what inspired Woolsey to call the summoned beasts Espers in Final Fantasy VI.

One of the uncanny espers from Final Fantasy Legend II.

Finally, because I mentioned Endora from Bewitched, I wanted to point out that it really seems like she’s named for the Witch of Endor, a character from the Old Testament who acts as a medium and channels the spirit of the prophet Samuel. What’s interesting about her role in the Bible is that she’s either good or neutral, depending on your interpretation, which you’d think would make Christians less opposed to witchcraft, extrasensory powers and the like. Nope!