If His Name Is Blanka, Why Is He Green?

This is part two in a series on the origins of Street Fighter II character names. This one mostly stands on its own, but it does build on some ideas introduced in part one, which details the origins for every character aside from Blanka. I’ve also made a video explainer for this post that you can watch here.

As far as the original Street Fighter II characters go, Blanka is… well, wild — literally, because he was raised by animals in the Brazilian rainforest, but also figuratively because he’s the exception to the rest of the World Warriors. Beyond the fact that he has green skin, Blanka stands apart because he doesn’t seem to be as much as a national stereotype as the rest of the cast, which includes a super serious American military dude, a beefy Russian in a Speedo who wrestles bears and an Indian yogi who, at least in early localizations of the game, gets fire-breathing powers from eating spicy curry.

However, because Blanka has been part of the core cast ever since the original Street Fighter II, he’s the precedent that has let Capcom stock future incarnations of this series with wackadoo fighters who might otherwise break the reality of what is, at heart, a story about an international martial arts competition. Hakan? Necro? Skullomania? You have Blanka to thank for paving the way in weirdness.

What is Portuguese for “rawr”?

Blanka was also a magnet for the attention of younger players. As someone who was nine when Street Fighter II debuted in arcades, I can tell you that he was the character most little boys gravitated to first. He looked like a freaky, Green Goblinish monster during the age of Ninja Turtles and other mutated freaks. But even though Blanka is representative of this trend in western kids’ entertainment, I’ve always suspected there was a deeper story behind how this character came to be. Having read every piece of Street Fighter II-related material I could get my hands on since I was a kid, I had a decent working knowledge of the origins of the other original Street Fighter II characters. I didn’t know much about Blanka, however, and most glaringly I couldn’t explain the question in this post’s title: Why the hell is he named something that seems like it should mean “white” if the most prominent thing about him is that he’s green?

This post does not provide an official, definitive answer given by a Capcom representative, because I don’t think one has ever been given, unless I’m mistaken. However, I think I have found the explanation that makes sense — or at least holds more water than the two most popular folk etymologies popularized by English-language message boards and wikis.

Just About Every Beastman Ever

Hailing from the depths of the rainforest, Blanka represents Brazil. However, of all the Street Fighter II characters, he looks the least like a stereotype of a given nationality. That’s not to say that Dhalsim is supposed to represent actual real-life Indian people or Zangief Russian people, but you can at least see how they work as distorted exaggerations of certain stereotypes. Looking at the history of Blanka’s evolution, it’s clear he was always different.

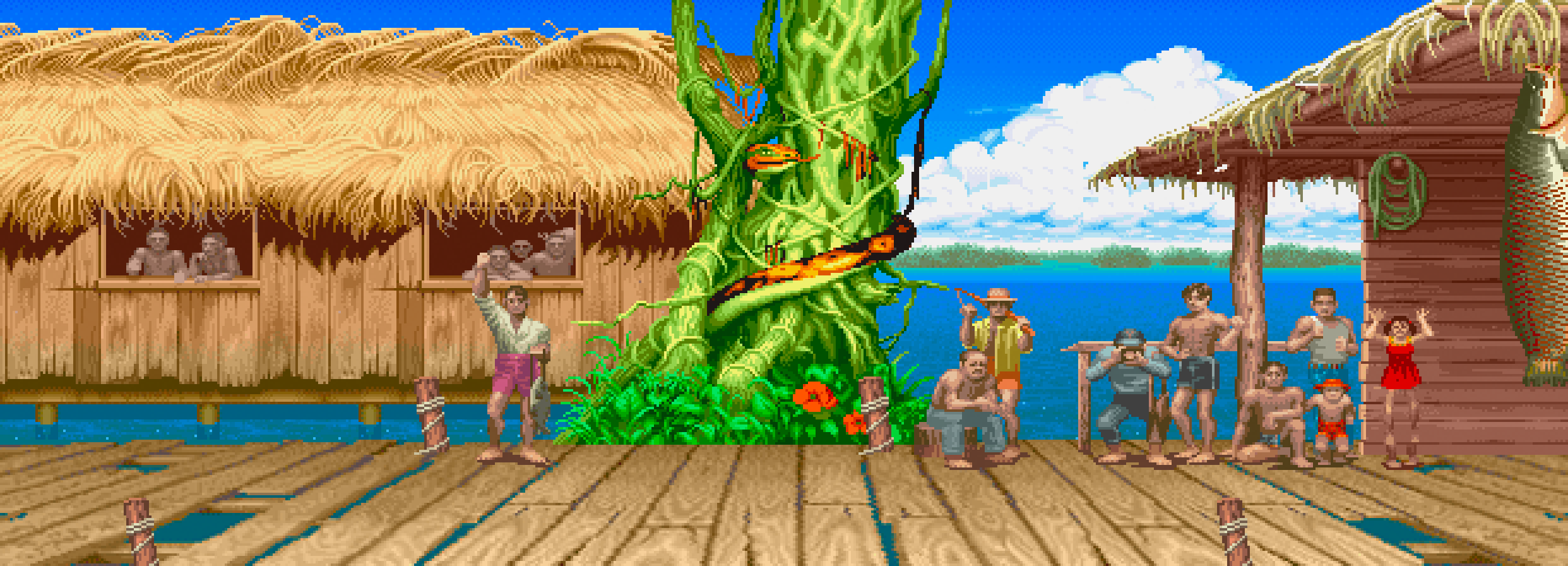

Versus specifically Rio de Janeiro for Laura’s stage in Street Fighter V.

We’re told that Blanka is not from the jungle originally, and his backstory explains why he’s different from the more normal-seeming Brazilian people you see in the background of his fishing village stage. He survived a plane crash, grew up among the animals of the Amazon, and somehow mutated in the process. The most frequently given explanation for his green skin is that living in the jungle, he survived on a chlorophyll-rich vegetarian diet that ultimately changed his natural pigmentation. This, of course, is not a thing that happens and not how being a vegetarian works; a lot of what goes for canon in Blanka’s storyline results from Capcom just saying that it is so, and we have to go along with it. In some versions of his backstory, it’s the lightning strike that brought down the plane that mutated Blanka and also gave him electricity powers; in other versions it’s electric eels that taught him how to do this. It’s all silly, but this is a game where people toss around fireballs like it’s nothing, so it’s maybe not worth worrying about too much.

Official backstory aside, I liken Blanka to Tam Tam and Cham Cham from the Samurai Shodown games. Set in an earlier era than Street Fighter, Samurai Shodown nonetheless has warriors from around the world convening to fight, and many of the non-Japanese Samurai Shodown characters represent, to one degree or another, some kind of stereotype. Tam Tam and Cham Cham hail from Green Hell, a South American location not tied to any modern-day nation and whose aesthetic incorporates elements of Aztec, Mayan, Incan, and other New World cultures. Like Blanka, the people of Green Hell seem closer to nature and more animal-like; Tam Tam howls like a beast when he wins a match, while Cham Cham scratches behind her ear like a dog.

It’s like that quote in the previous post where Yoko Shimomura explained that she composed the Street Fighter II music not based on real-life things but instead based on the idea of those things: In this case, the thing isn’t an actual country so much as the idea of this mythical, wild place that is green and dangerous.

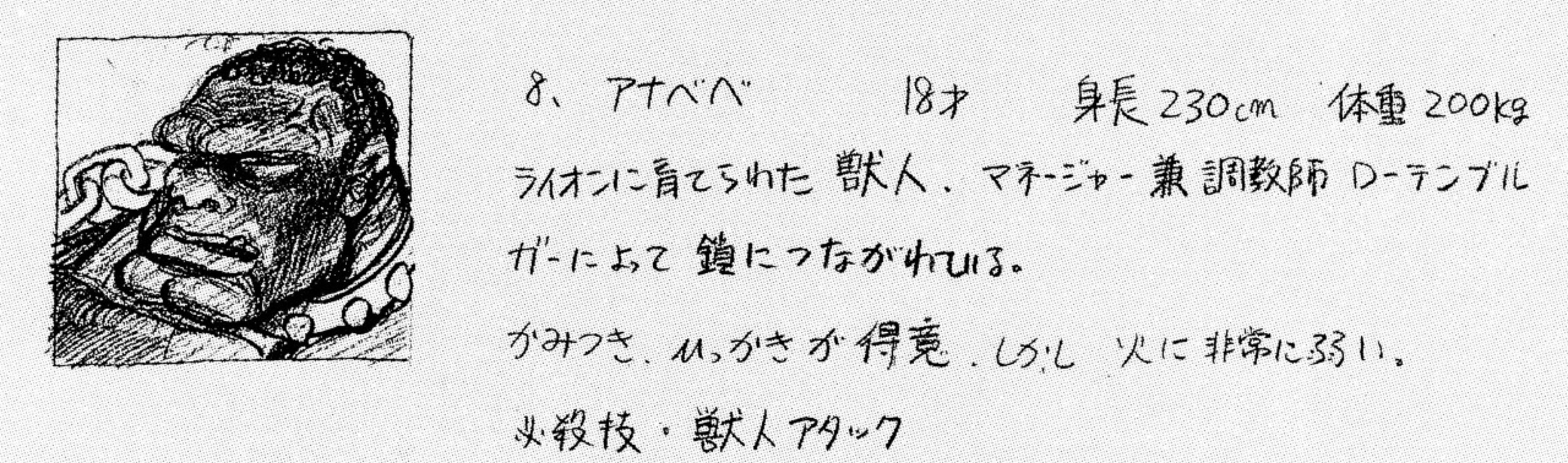

In fact, the earliest conceptions of Blanka didn’t put him in the Brazilian jungle but in the wilds of Africa. The character who would become Blanka was originally Anabebe, an African man “raised by lions” and kept “shackled in chains” by a character named Rothburger. Which… is a horrendously racist caricature people would have found inappropriate, even back in 1991 — even among the parade of stereotypes that was Street Fighter II. (The series would not get a representative of any African country until Street Fighter III’s Elena, who hails from Kenya.)

Translation: Anabebe, 18 years old, height: 230 cm, weight: 200 kg. Anabebe is a beastman raised by lions. His manager and tamer, Rothenberger, keeps him shackled in chains. Anabebe is proficient at biting and scratching, but is extremely weak to fire. Special move: Beastman Attack.

Probably not coincidentally, Anabebe shares his name with an African warrior character in the manga Jungle King Tar-chan. It’s implied on the Street Fighter Wiki that this discarded character idea is somehow linked to Damnd, a hulking Dominican fighter appearing at the end of the first stage in Final Fight. (Some sources credit Akira “Akiman” Yasuda with designs for both, but in this Capcom roundtable, Akiman credits a different designer, “Pigmon,” with creating Blanka.) In moving toward the finalized design, Capcom considered a ninja-type warrior and one inspired by the title character in the manga Tiger Mask, which notably would end up inspiring the bestial fighter King in another series, Tekken.

Left to right: Tiger Mask Blanka, Ninja Blanka and the almost-there Hamablanka (a.k.a. Hammer Blanka).

The next phase of the character’s evolution is “a large man with thick hair and sideburns” named Hamablanka, sometimes erroneously rendered in English as “Hammer Blanka,” at which point the designers decided to make him look increasingly animalistic. With this, we’re basically at the character we all know and love, and his name would get truncated down to just “Blanka.”

There is speculation online that Blanka’s design and backstory were influenced by characters such as the Tiger Mask character Gorilla Man and the Ashita no Joe character Harimau. These both seem likely, but I couldn’t find anyone from Capcom saying they figured into Blanka’s creation. In Udon’s How to Make Capcom Fighting Characters guide, Yasuda merely points out the general trend in media at the time, saying, “Looking back on it now, it might seem bizarre that we ever had a ‘man-beast’ slot in our roster, but at the time it was indispensable part of any great martial arts shonen manga, from Ashita no Joe to Tiger Mask.”

According to this blog, the first-party NES game Pro Wrestling features a character that also contributed to Blanka’s look and moveset, and this one is actually backed up: According to an interview in the Art of Street Fighter book with Akira Yasuda and the other co-lead designer on Street Fighter II, Akira Nishitani, this character did at least help inspire one of Blanka’s moves, through you have to admit the resemblance is strong. As Yasuda explains:

The Famicom Disk System had a professional wrestling game with a half-fish type character called The Amazon. Nishitani would use this one biting move over and over again, and I paid homage to that frustration I felt during those times through Blanka’s chomping action.

In the How to Make Capcom Fighting Characters book, Yasuda brings up The Amazon again but stops short of making a direct link between him and Blanka but acknowledges the similarity: “The Merman who appears in that [game] is of the same ‘man-beast’ category, come to think of it.”

He’s more Creature from the Black Lagoon than beastman, but The Amazon is nonetheless a green-skinned menace with a mouth full of sharp teeth — like Blanka.

Notably, The Amazon’s green skin was not necessarily always in the cards for Blanka. In this interview, Yasuda says that at one point in the design process, the character had pink skin, but Yasuda changed it to green because he felt the pink version was “disgusting.”

This brings us to issues of color and names. To restate the big question, why would his name be Blanka (ブランカ or Buranka), which is very close to the Portuguese word for “white,” branco, when his green skin is one of his most defining characteristics?

The “White Man” Explanation

Either because it’s not true or because there’s just no evidence to support it, the prevailing explanation in the early 2000s has since been stripped from Blanka’s Wikipedia page, though debate about it still exists on the talk page and on lesser wikis. This theory states that Blanka’s name comes from the Portuguese phrase homem branco, or “white man,” and that Hamablanka may itself be a warping of this phrase into Japanese and then into English. That said, a lot of explanations for this theory actually cite the original phrase as hombre blanco, even though that’s Spanish for “white man” and not Portuguese. According to this theory, Blanka was light-skinned before he mutated into the green, electrified beast he is today, and therefore the native Brazilians knew him as “the white man.”

Um homem verde, claramente.

The argument against this theory is that many Brazilians have light skin, and therefore a light-skinned person wouldn’t necessarily be so conspicuous or unusual. You’d think most people would seize on the whole “boy being raised by animals in the jungle” thing instead of being “wow, he’s white!” — and even then, by the time average Brazilians learned who he is, Blanka doesn’t have light-colored skin because he has green skin. Beyond all that, if his name did come from blanco or branco, you have to wonder how he ended up with what seems like the feminine version: blanca or branca.

Like I said at the beginning of this post, the version of Brazil put forth in Blanka’s stage doesn’t exactly demonstrate that Street Fighter II’s designers were interested in making a realistic depiction of modern Brazilian life. If I wanted to be generous with this theory, I suppose I’d say that it’s possible this attitude could have also resulted in a bad translation or the wrong Portuguese word being picked. If Capcom was working with limited or second-hand knowledge about Brazil and Portuguese — or if they were just, you know, winging it, figuring no one would be overthinking it thirty years after the fact — maybe an entirely wrong phrase like hombre blanco really did bring about this character’s name, despite all the reasons it doesn’t make sense.

After all, Blanka’s backstory doesn’t make sense. There’s not a great reason Capcom can really give for why a plane crash made him green, yet here he is, green as The Hulk, all these years later. If anything, the best explanation for why Blanka is green is that Yasuda found the pink version of the design disgusting, and once he was recolored green, Capcom just dashed together an explanation for it.

But then again, if his name was Hamablanka before his skin got turned green or even before the whole “raised in the rainforest” aspect of the character was finalized, then maybe there’s a different reason for the name.

The Memory Loss Explanation

There is a second explanation for Blanka’s name that you may encounter online It states that branco is a Portuguese term relating to memory loss, the connection being that Blanka has amnesia as a result of the plane crash. This attempt at an explanation allegedly connects with his ending in Street Fighter II, where he meets his birth mother, whom he does not initially recognize.

I don’t think this one is correct, either. It actually seems like a bigger stretch than the “white man” explanation, simply because branco is not used in Brazilian Portuguese to refer to a total loss of memory so much as a temporary failure to remember, similar to how English speakers use the expressions “blanking” or “drawing a blank.” In any case, the series isn’t super clear when Blanka landed in the jungle — whether he was a baby or a young boy. It’s also not clear from the game that Blanka is actually amnesiac; perhaps he was just too young when the plane crashed to remember her in the first place.

In the Street Fighter II ending, Blanka’s mom recognizes Blanka because she thinks his anklets are actually the ones she gave to him before the crash… even though said anklets are fully adult-sized — big enough to fit around Blanka’s beefy beastman legs. I think this is the storyline just incorporating design elements after the fact in the style of Capcom thinking up reasons why Blanka turned green. I’d actually bet good money that Blanka’s anklets are actually holdovers from when he was Anabebe, the shackled wildman, and they persisted through the design process long after that initial storyline was abandoned. Unless this ending was planned from the character design stages, I’d guess it’s more “what can we do with this character?” than it is Capcom baking in an anklet-centric epilogue right from the beginning.

A Resort in Wakayama

And here’s what I think really happened.

In 1971, the New Shirahama Tropical Botanical Garden was reinvented as a “leisure facility” and tourist attraction Hama Blanca (ハマブランカ), Hama from 浜, “beach,” and Blanca allegedly a nod the Moroccan city of Casablanca, at least according to the Japanese Wikipedia page. (EDIT: It was been pointed out to me after this went live that Shirahama also literally means “white beach.”) Doing a healthy tourist trade during its heyday, Hama Blanca retained the gardens and added a musical revue. While none of it seems specifically Brazilian or even South American in focus, the traces remaining online today give a sense of a jungle paradise and tropical climes beyond what would naturally occur in the resort town of Shirahama.

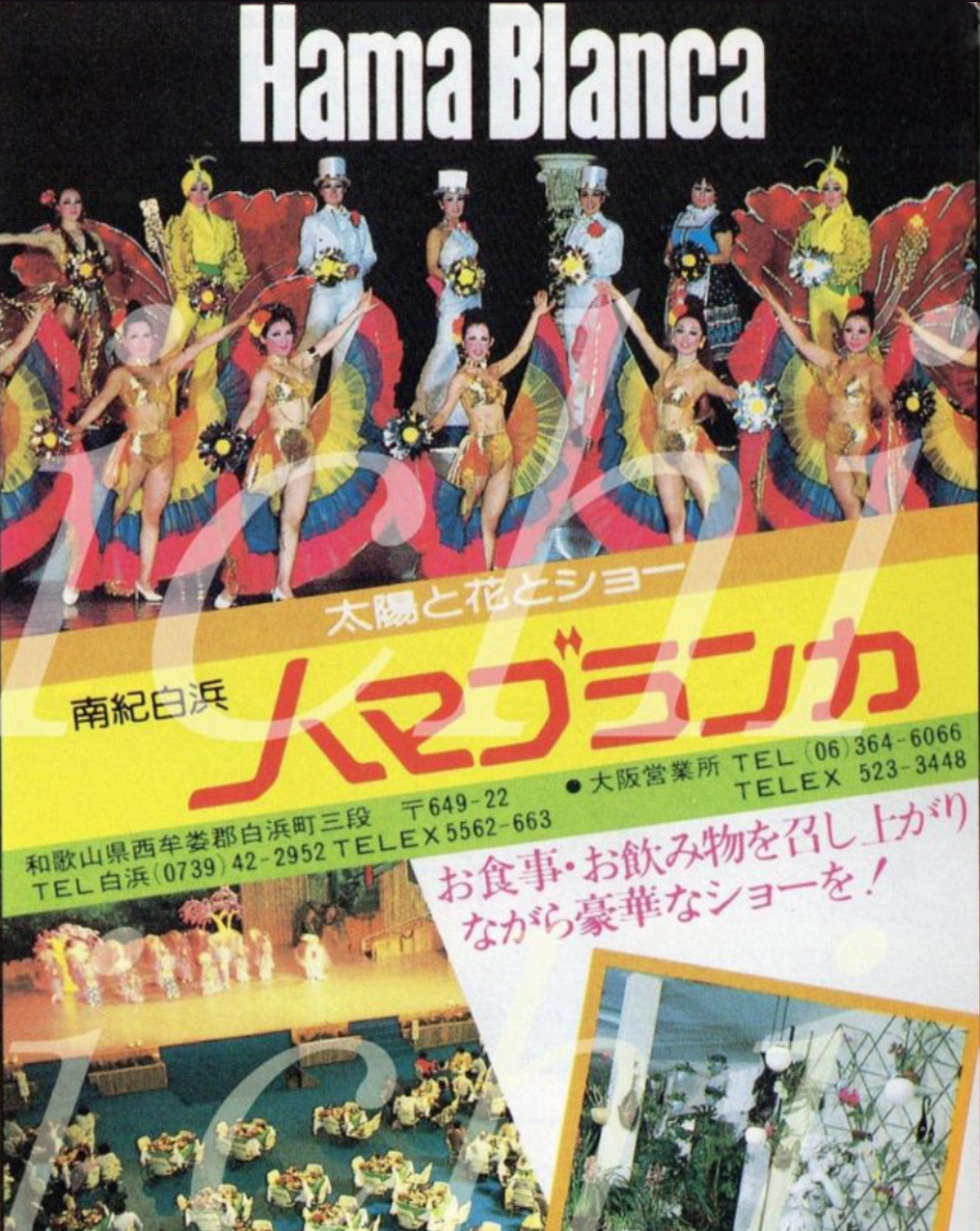

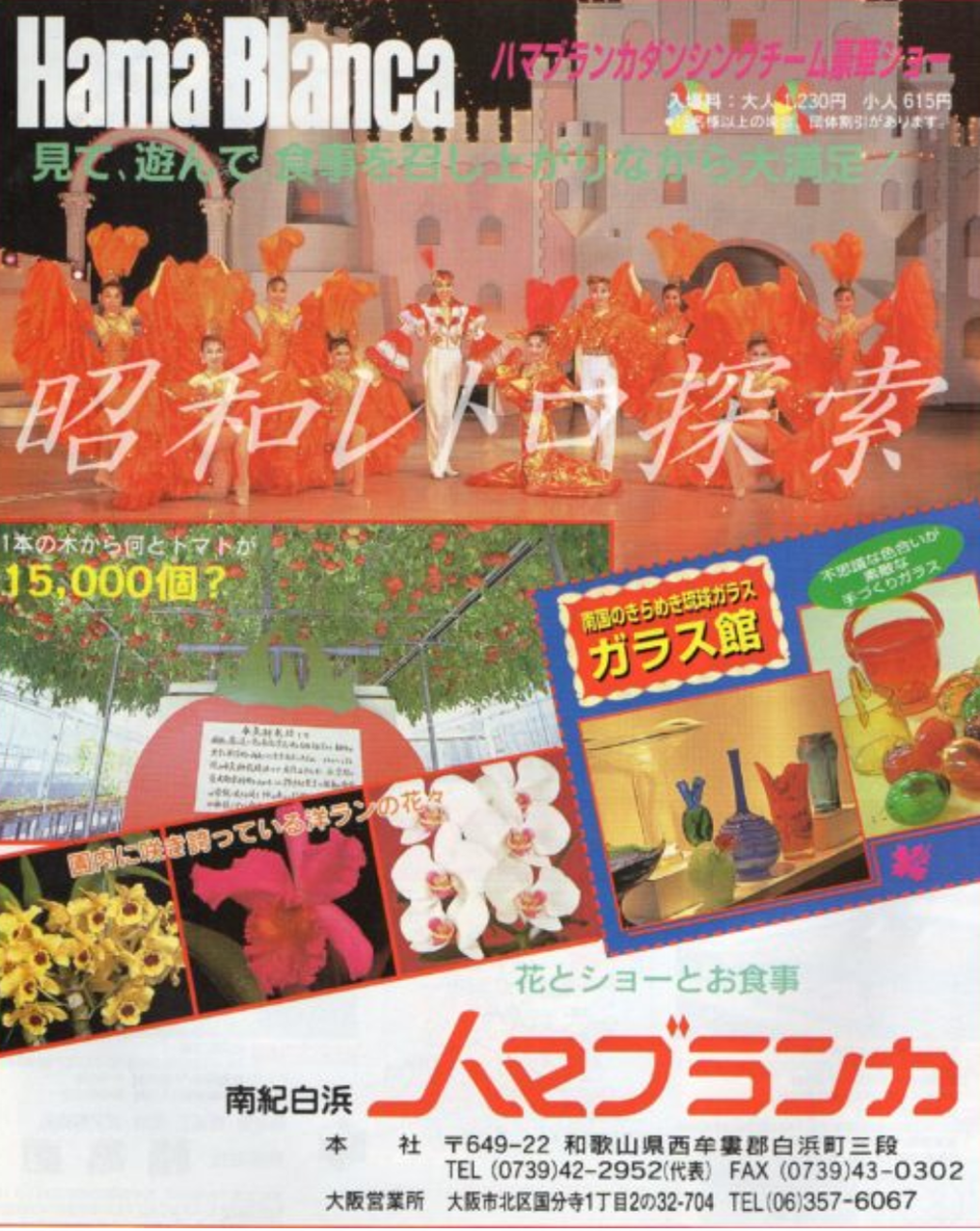

Hama Blanca’s advertisements showed off the plants in its gardens and greenhouses but forefronted its stage shows, which featured dancers in costumes that sometimes seemed to take inspiration from those you might see at Carnival. All three poster images via this blog.

Left: A video from 1998 titled “Hama Blanca Opening,” featuring one of the live musical shows from the last era in which they were performed at the resort. Right: A video from 1991 titled “Shirahama Onsen, Hama Blanca and the former Hotel Tenzankaku,“ though I’m not clear which portions of the video are showing Hama Blanca specifically.

By 1998, a recession forced Hama Blanca to scale back its offerings and focus on the gardens, pausing other attractions. The park closed permanently in 2005. The buildings have been demolished; it is said that only palm trees and some ruins remain as proof that a tropical getaway ever existed in this spot.

But as you might be able to guess, it’s possible that an unlikely relic of Hama Blanca is everyone’s favorite green Brazilian. As far as I found, the only English-language page connecting Blanka and Hama Blanca is the TV Tropes page for Street Fighter II characters, which points out that Wakayama prefecture is somewhat close to Capcom’s headquarters in Osaka. By today’s estimates, it’s a 90-minute train ride or an hourlong drive down the coast, which does in fact make it seem close enough that the folks who made Street Fighter II at least would probably have been familiar with advertisements for Hama Blanca.

The reason I think Blanka was named for this resort destination is that, quite simply, there’s no other reason for the name he had during the planning process, Hamablanka, to exist. The brand name Hama Blanca is a unique yoking together of Japanese and this Latinate word for “white” wherein it’s not actually being used to signify the color white. I suppose you could interpret the name of the resort as a fancy, international rendering of “white beach,” but I think more than anything, “Blanca” in this context is just suggesting a culture beyond Japan — something wild and green, something boasting the multicolor palate of the tropics rather than something merely white and certainly something altogether different than its Mediterranean namesake, Casablanca. In the way that Blanka the character doesn’t so much capture the nation of Brazil but the idea of the wild jungle, Hama Blanca was painting with broad, bright strokes to give tourists a getaway to somewhere different than where they were.

I have to admit that it’s a gut feeling that prompts me to think this is the true source of Blanka’s name, or at least a more plausible candidate than the previous two theories. I’m a sucker for a good story about an abandoned amusement park, and there is something strange but poetic in this aspect of someone else’s pop culture nostalgia being captured in the most unlikely of places: the grunting beastman from Street Fighter.

To my knowledge, this is not a connection that anyone associated with Street Fighter has acknowledged. As the previous post should indicate, Capcom seems a little freer to admit when the inspiration for a character comes from a Japanese institution — Guile’s name coming from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, for example — but I have no idea if Hama Blanca being a brand name owned by someone else might prevent Capcom from admitting it led to one of its characters. For what it’s worth, its official localizations spell the older, longer name as “Hamablanka,” but the choice to spell it differently might not be significant, as the Japanese ブランカ could be translated just as easily as Blanca or Blanka.

Based on this, can we least agree that “Hammer Blanka” was most likely an incorrect rendering of that old name?

And that is everything I could find about this character. Again, I am not certain that Capcom named him after the resort, but I do think this is the best explanation out there — and one that is harder to disprove than the first two, at least. As is the case with any post here, I want anyone with evidence — a mention by a Capcom staffer being the best version of that — to hit me up. I will update this post accordingly.

Miscellaneous Notes

In the previous Street Fighter II post, I mentioned how I don’t think it’s likely that Dhalsim was named for an Indian restaurant near Capcom’s main offices. But the fact that Blanka probably was named for a different establishment somewhat near Osaka makes me think this explanation is slightly more likely. Like, if they named one character after a random place they knew of, I suppose it’s possible they could have done it twice. I still want to know who Dhalisma is, though.

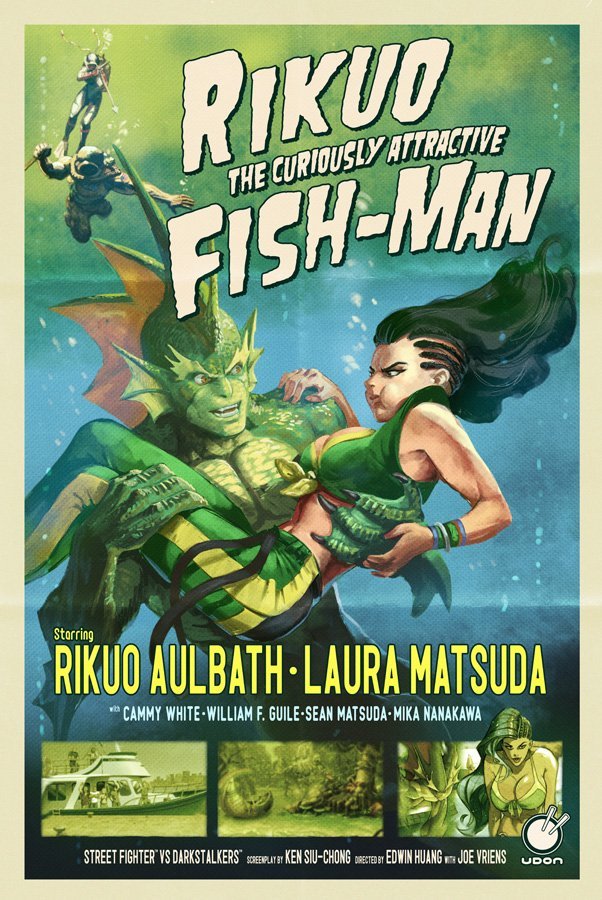

Capcom finally got around to giving Brazil a new representative in Laura, who debuted in Street Fighter V. Her signature color is green, and she, like Blanka, can manipulate electricity in her attacks, which works as a nice callback to the original Brazilian Street Fighter before Blanka joined the roster as well. And you could also argue that Darkstalkers has a sort of nod to Blanka in the form of Rikuo, another green representative of Brazil and a Creature of the Black Lagoon-type whose backstory recalls the primordial natural world that Blanka comes from.

Speaking of Laura, she has a connection to something that kicked off the Street Fighter discussion in the previous post. Laura is just one member of the Matsuda family, a Brazilian-Japanese family of martial artists. The first member introduced into the series was Sean, who debuted in Street Fighter III. Unlike Laura, who practices Matsuda jiujitsu, Sean’s martial art style is an imitation of Ryu and Ken’s Shotokan karate. I could swear I remember reading at some point that his name was chosen to represent the first syllable in Shōryūken, and now I can’t find it. It’s close, I suppose, but his name is rendered in katakana as ショーン・マツダ.

Not currently playable in any Street Fighter title.

Though she has yet to appear in an actual game, there exists a female version of Blanka, Blana, who was created as a joke character for Capcom’s Street Fighter V presentation at the Brasil Game Show in 2015, during which Laura was revealed. Street Fighter V director Takayuki Nakayama joked on Twitter that Blana is Blanka after having been subjected to Demitri’s Midnight Bliss move from Darkstalkers — and indeed that version of Blanka appears on the variant cover for the second issue of the Street Fighter vs. Darkstalkers comic. The other variant cover? It features Rikuo and Laura in a send-up of a poster for a Creature From the Black Lagoon-style movie.

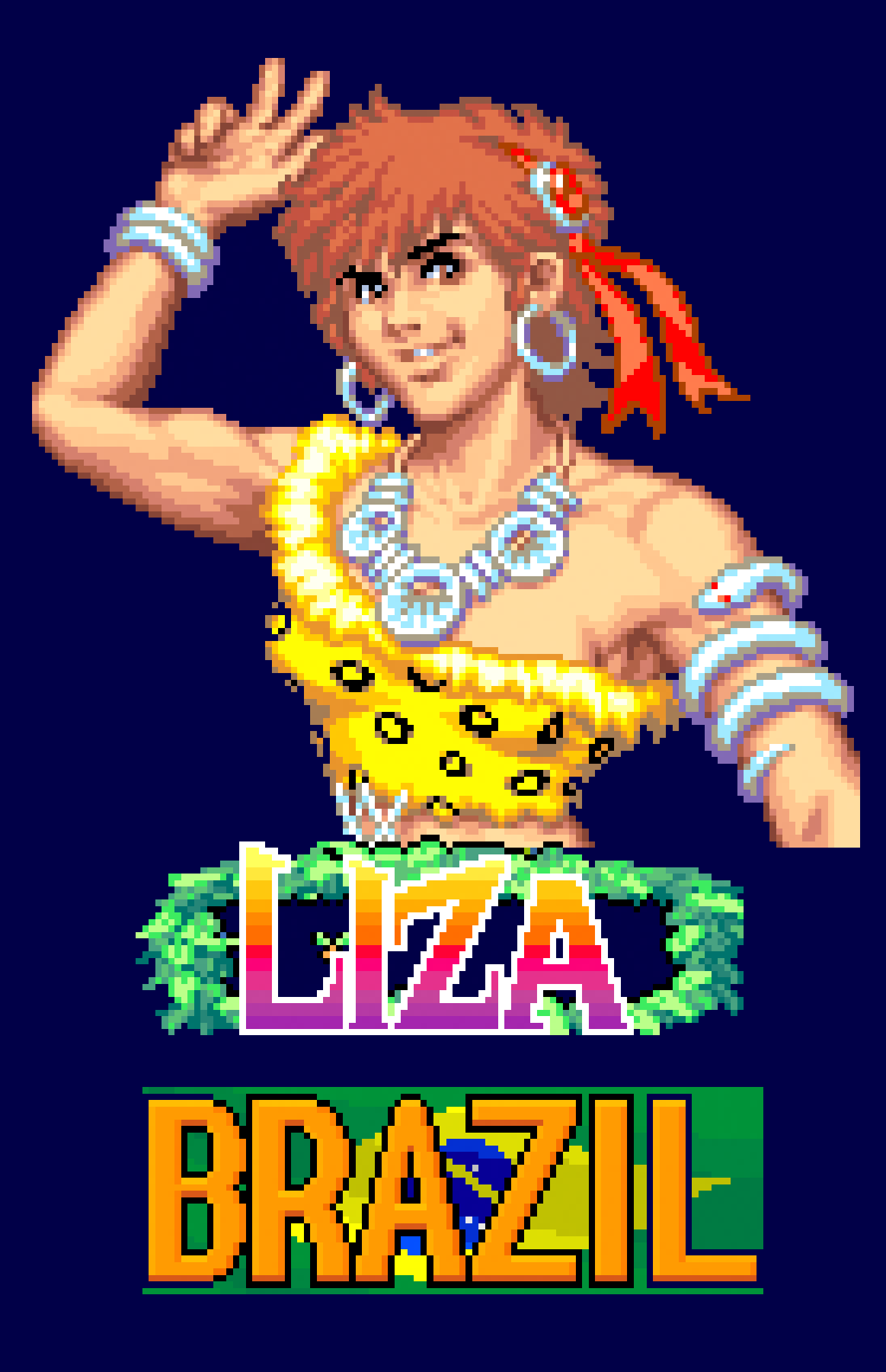

Watching this video, I learn about the 1994, the Taito-developed fighting game Kaiser Knuckle, known outside Japan as Global Champion. It features a character named Liza who serves as a sort of fusion of Blanka and Cham Cham. She’s a petite jungle girl rocking cheetah print and accompanied into battle by a monkey *and* a cockatoo. However, she is made to explicitly represent Brazil, in that she enters the game’s martial arts tournament specifically to buy a fancy outfit for Carnival. She is the from-the-ground-up Brazil representative that Capcom never intended Blanka to be.

Because this ended up being the flashiest of the articles that were published when the site went live, I went ahead and did a video explainer for the whole thing. Here is that, although if you have made it to the end of this piece, I feel like you don’t need to hear me talking through these points again. But you know what? You do you.

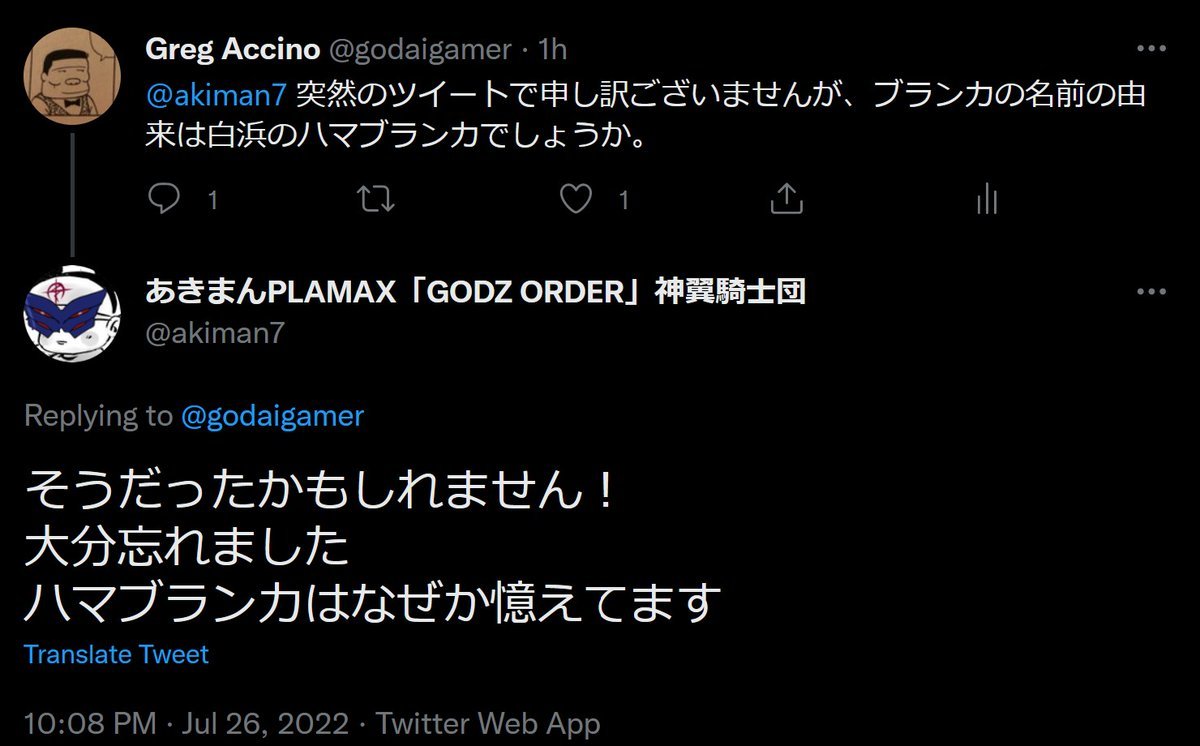

EDIT: After the video went live, Greg Accino asked Akira Yasuda if my theory about Hama Blanca was correct.

Yasuda’s response, translated: “Maybe! I’ve totally forgotten. For some reason I still remember Hama Blanca.” Which does not answer anything conclusively, I realize, but still.